By Alexis Buckley, Research

Each year the MHS grants a number of research fellowships to scholars from around the country. Our four fellowship programs bring a wide variety of researchers to the MHS. See the list of incoming 2018-2019 fellows and their project titles below. You can learn more about each fellow’s research at their MHS brown bag lunch talk—keep an eye on the calendar to find out when they’ll present!

This year we offered 23 short-term fellowships to scholars whose research brings them to the MHS, including a new fellowship for a project on American religious history, the C. Conrad and Elizabeth H. Wright Fellowship. (See page 8 of our last newsletter for details!)

We talked about our collaboration with the National Endowment for the Humanities in our last blog post. This collaboration allows us to offer long-term fellowships, where the researchers spend 4-12 months as part of the MHS community. We also partner with the Boston Athenaeum to offer a Loring fellowship for a researcher studying the Civil War, its causes and consequences. The Athenaeum’s Civil War collections are anchored by its holdings of Confederate states imprints, the largest in the nation. The Society’s manuscript holdings on the Civil War include diaries, photographs, correspondence from the battlefield and the home front, papers of political leaders, and materials on black regiments raised in Massachusetts.

The MHS is also proud to be a founding member of the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium, a collaboration of over two dozen major cultural institutions across New England. Each year, the Consortium offers fellowships to researchers whose projects bring them to NERFC member archives. This year, 11 of the 2018-2019 NERFC fellows will be researching at the MHS.

We are looking forward to welcoming all our 2018-2019 research fellows, and learning more about their work on 20th-century reform movements, 17th-century mercantilism, and all points in between!

*****

Suzanne and Caleb Loring Fellows on the Civil War, Its Origins, and Consequences

Jean Franzino

Beloit College

Dis-Union: Disability Cultures and the American Civil War

MHS Short-term Fellowships

African-American Studies Fellow

Crystal Webster

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Beyond the Boundaries of Childhood: Nineteenth Century Black Children’s Cultural and Political Resistance

Andrew Oliver Fellow

Ann Daly

Brown University

Hard Money: The Making of a Specie Currency, 1828-1860

Andrew W. Mellon Fellows

Nicholas Ames

University of Notre Dame

Communities of Difference in 19th Century Irish-America

Caroline Culp

Stanford University

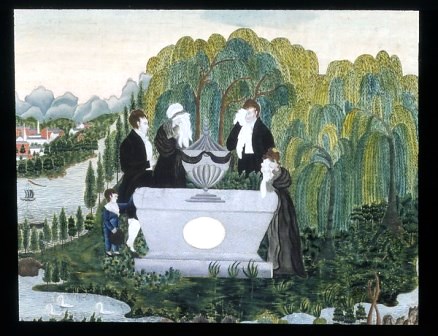

The Memory of Copley: Afterlives of the American Portrait, 1774-1920

Timothy Fosbury

University of California, Los Angeles

Persistent Archives and the Early Americas, 1600-1830

Madeline Kearin

Brown University

Sensory Experiences of Daily Life at New England Hospitals for the Insane

Andrew Kettler

University of Toronto

Odor and Power in the Americas

Molly Laas

University Medical Center Göttingen

Moral Measurements: Wilbur Olin Atwater and the Making of the American Diet

Kirsten Macfarlane

Cambridge University

The Reception of European Biblical Scholarship in Early North America

Adam Mestyan

Duke University

American Travelers in the Middle East, 1830s-1930s

Molly Reed

Cornell University

Ecology of Utopia: Environmental Discourse and Practice in Antebellum Communal Settlements

Benjamin F. Stevens Fellow

Dexter Gabriel

University of Connecticut

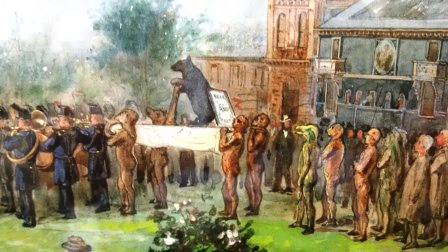

A West Indian Jubilee in America: Mapping August First in New England

C. Conrad & Elizabeth H. Wright Fellow

Jennifer Rose

Claremont Graduate University

The World Becomes Round: Early Encounters between Bombay Parsis & Yankee Merchants, 1771-1861

Louis Leonard Tucker Alumni Fellows

Nicole Breault

University of Connecticut

The Night Watch of Early Boston, 1662-1776

Matthew Fernandez

Columbia University

Images Abroad: Henry Adams and the Picturing of Modernism

Xiangyun Xu

Pennsylvania State University

The American Debate over the China Relief Expedition of 1900

Malcolm and Mildred Freiberg Fellow

Diego Pirillo

University of California, Berkeley

Renaissance Books in Early America: John Winthrop Jr. and Italian Occultism

Marc Friedlaender Fellow

Nicole Williams

Yale University

The Shade of Private Life: The Right to Privacy and the Press in American Art, 1875-1900

Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati Fellow

Roberto Flores de Apodaca

University of South Carolina

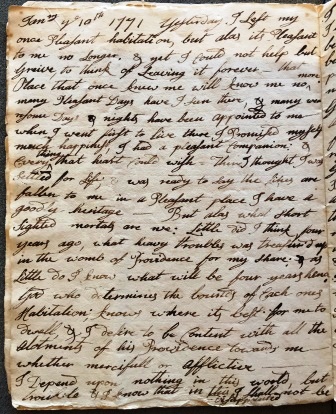

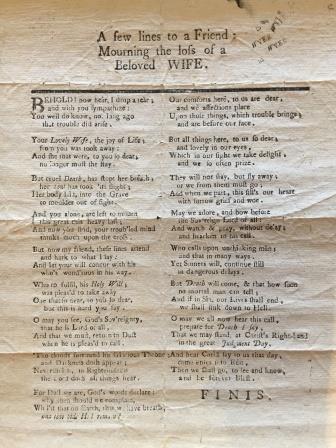

“Alas my Backsliding Hart!”: Religious Worldview and Culture of New England Continentals 1775-1783

Ruth R. & Alyson R. Miller Fellows

Shealeen Meaney

Russell Sage College

Boston meets Brahmin: Massachusetts Women in Gandhi’s India

Christopher Stampone

Southern Methodist University

“[A]s if she were born to empire”: Isabella, the Bildungsroman, and the Establishment of a New American Society Identity in Catharine Maria Sedgwick’s The Linwoods

W. B. H. Dowse Fellows

Taylor Kirsch

University of California, Santa Cruz

Indigenous Land Ownership in the Praying Towns of the New England Borderlands: Indigenous Lives Lands and Legacies of Seventeenth Century Massachusetts

Ian Saxine

Alfred University

The End of War: Indians, Empires, and Identity in the American Northeast, 1713-1727

MHS-NEH Long-term Fellowships

Mara Caden

Yale University

Mint Conditions: The Politics and Geography of Money in Britain and Its Empire, 1650-1760

Brent Sirota

North Carolina State University

Things Set Apart: An Alternative History of the Separation of Church and State

New England Regional Fellowship Consortium Fellows

Doris Brossard

Rutgers University

The “‘right’ to indulge in the act of sexual intercourse”: Unmarried People, Sex, and the Laws on Contraception in Massachusetts (1960- 1972)

Daniel Burge

University of Alabama

A Struggle Against Fate: The Opponents of Manifest Destiny and the Collapse of the Continental Dream, 1846-1871

Christina Casey

Cornell University

Lady Governors of the British Empire

Donna Drucker

Technische Universität Darmstadt

The Study of Human Sex Problems: A History of American Sexual Science, 1895–1945

Susan Eberhard

University of California, Berkeley

American Silver, Chinese Silverwares, and the Global Circulation of Value

David Faflik

University of Rhode Island

Passing Transcendental: Harvard, Heresy, and the Modern American Origins of Unbelief

Alexey Krichtal (MHS)

Johns Hopkins University

Liverpool, Slavery, and the Atlantic Cotton Frontier, c. 1763-1833

Katherine McIntyre (MHS)

Columbia University

Maroon Ecologies: Albery Allson Whitman and the Place of Poetry

Gwenn Miller (MHS)

College of the Holy Cross

“You Will Bring Opium to Canton”: John Perkins Cushing and Boston’s Early China Trade

Joshua Morrison (MHS)

University of Virginia

Cut from the Same Cloth: Salem, Zanzibar, and American-Omani Trade (1820-1870)

Peter Olsen-Harbich (MHS)

College of William and Mary

A Meaningful Subjection: Coercive Inequality and Indigenous Political Economy in the Colonial American Northeast

Camille Owens (MHS)

Yale University

Blackness and the Human Child: Race, Prodigy, and the Logic of American Childhood

Traci Parker

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Workers, Consumers, and Civil Rights

Fabricio Prado

College of William and Mary

Inter-American Connections: North-South American Networks in the Age of Atlantic Revolutions

Kimberly Probolus

George Washington University

Separate and Unequal: The Rise of Special-Selection Programs in Boston, 1950–2000

Wendy Roberts

State University of New York, Albany

Itinerant Politics: Settler Colonialism and the Evangelical Long Poem

Josh Schwartz

Columbia University

Pictures: Charles Dana Gibson, John Sloan, and the Making of Modern Americans

C. Ian Stevenson (MHS)

Boston University

“Army Tales Told While the Pot Boiled”: The Civil War Vacation in Architecture and Landscape, 1880-1910

Hannah Tucker (MHS)

University of Virginia

Masters of the Market: Mercantile Ship Captaincy in the Colonial British Atlantic, 1607-1774

Thomas Whitaker (MHS)

Harvard University

The Missionary Republic: The Rise of Evangelical Missions in the United States, 1789-1819

Rhaisa Williams

Washington University in St. Louis

Shuffling, Shouting, and Wearing Down: Rethinking the Techniques of Protest in Welfare Rights Organizations

Nathaniel Windon (MHS)

Pennsylvania State University

Gilded Old Age: Inheritance and American Literature, 1877-1918

Kari Winter

State University of New York, Buffalo

Fourteenth: Vermont’s Struggle For and Against Democracy, 1775-1875

Colonial Society of Massachusetts Fellowship

Andrew Rutledge (MHS)

University of Michigan

“We have no need of Virginia Trade”: New England Tobacco in the Atlantic World