By Christina Carrick, Publications

In Paxton, Mass., on 3 February 1783, a riot broke out over a cow. More than a dozen “hearty fellows” from Paxton and nearby Worcester County towns stormed a “vendue” (an auction) and attempted to “rescue” a cow from the auction block. They broke through the bars penning the animal and, wielding “unusual” clubs, threatened the life and well-being of anyone who dared to place a bid. According to one witness, Paxton joiner and alleged rioter Asa Sterns said that “whosoever bids, bids at his peril” while Holden yeoman Jonathan Wheeler threatened “the first man that bid he’d knock his brain out.”

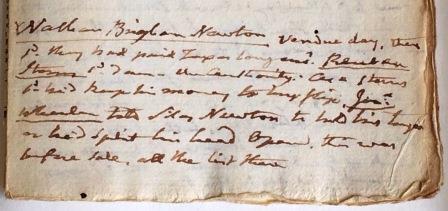

The rioters left a trail of bruises and sore heads behind them. No one was killed in the commotion, but 10 men were later arrested, charged with inciting a riot, and tried before the September Sessions of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Worcester, prosecuted by Atty. Gen. Robert Treat Paine. The defendants were indicted for congregating in order to

obstruct the due Execution of Law and to prevent the Collection of the public Taxes of this Commonwealth legally assessed on the Subjects thereof for the defence of their Liberty and happiness with force and Arms riotously routously and unlawfully did assemble and gather together for the destructive purposes aforsaid and to disturb the peace of the Commonwealth and being so assembled and gathered together, did then and there unlawfully riotously & routously remain and continue together in a tumultous manner for the space of one hour in evil Example to others to offend in like manner & against the peace & Dignity of the Commonwealth.*

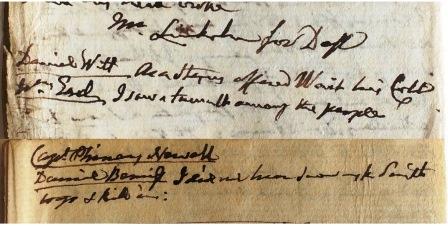

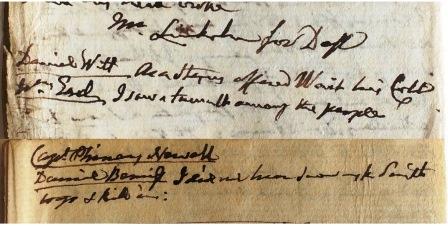

In the small, makeshift notebooks that contain Paine’s hastily written trial notes, the cramped pages of witness and participant testimonies expose local, state, and class tensions. Witness after witness reported that the individuals in question, most prominently Asa and Reuben Sterns, had spoken against the state government in the weeks before the riot. Most of the Sterns brothers’ complaints addressed state taxes and more specifically the state resolve that allowed tax collectors to confiscate moveable property or livestock—the aforementioned cow—if an individual did not have specie (coin money).

Due to the shortage of hard money and the Revolutionary War’s interruptions of business-as-usual, many Paxton residents were cash-strapped and struggling to answer the intensifying state tax demands. Consequently, local officials confiscated cattle from the Sterns brothers and several other residents in lieu of unpaid taxes. Local residents saw this measure as grossly unjust. They argued that if their cattle—part of their means to a living—were confiscated, it would make it harder to earn the money to pay taxes, or even to eat. According to witness Thomas Pollard, “Asa Sterns sd. he wd. pay no more Taxes, if he did he shd. have no more money to pay Taxes.” The tax rioters complained that the coastal merchant elites were growing wealthy at their expense. David Pierce, one of the alleged rioters, swore at the trial that he was “fighting for liberty but it was become Tyranny & he wd. support it no longer” because the tax “money went to support great men.”

The resentment toward the state grew so high, witnesses reported, that after a few drinks the Sterns brothers proclaimed that Worcester County residents would be better off under the British government than the Massachusetts government. They had toasted the “brave Tories” and wished health to King George III. Other witnesses stripped the rioters of ideology and instead said that Asa Sterns “sd. if he pd. the 5 Doll for Taxes he shd. have no money to buy flip”—an alcoholic beverage popular in early New England.

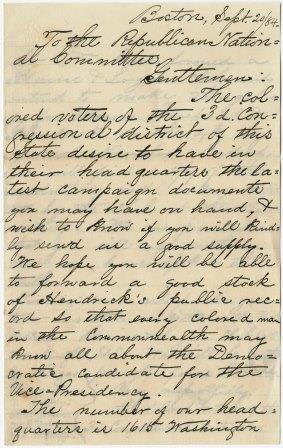

On the February morning of the vendue, Reuben and Asa Sterns, David Pierce, and a number of other men arrived at the auction site with clubs, intending to stop the sale and prevent wealthier locals from purchasing their cows. Testifier Nathan Brigham Newton observed the buildup to the riot:

Vendue day, they sd. they had paid Taxes long enô. Reuben Sterns sd. damn the Authority. Asa Sterns sd. he’d keep his money to buy flip. Jona. Wheeler told Silas Newton to hold his tongue or he’d split his head open. this was before sale

Nathan Brigham Newton’s Testimony

The riot’s violence lasted less than an hour, with rioters targeting the state authorities and local tax collectors or trying to release the cattle from the auction pen and nearby barn. Some locals that were “freindly to Gov” drove the cattle back into the barn before the rioters could make off with them. The rioters were disbanded and indicted two months later.

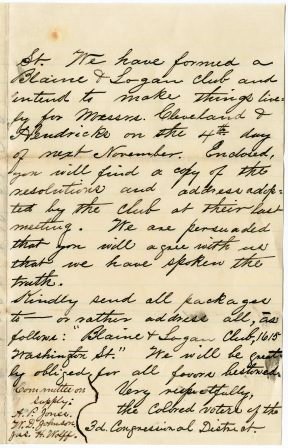

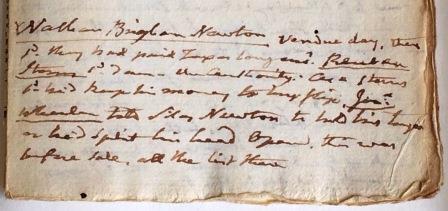

The case was not as legally challenging as many that Paine faced. Levi Lincoln, attorney for the defense, presented thin arguments that fill barely half a page in Paine’s notebook, whereas the witness testimonies take up over a dozen. Paine noted when one defense witness stated that the rioters had not actually threatened murder, but his remaining defense notes are short and cryptic. Unlike many cases, he did not spend pages listing relevant legal texts, past case precedents, or rationalizing the charges—the case was straightforward. The 10 men were found guilty of inciting a riot and sentenced to each pay fines of £4 to £10 and sureties of £50 to £80 for a term of two years to guarantee their good behavior, while one man was sentenced to three months imprisonment. The cattle proceeded to auction; the proceeds from the sale went to the state government. Despite the relative legal simplicity, the case indicates broader tensions in Revolutionary Massachusetts.

Paine’s notes on Levi Lincoln’s arguments for the defense

Paine prosecuted several rioting cases in 1783. The same September court in Worcester County tried cases for riots in Sturbridge, Dudley, Douglass, and Petersham. These cases resemble the Paxton riot, with men resentful about taxation, confiscated livestock, and debt. The complaints underpinning these disturbances resurfaced in a larger protest movement later in the decade: Shays’s Rebellion. While the Revolutionary War drew to a close in 1783, Massachusetts residents continued to contest the shape and function of the new state government.

For the full trial story and Paine’s other legal endeavors, check out the Robert Treat Paine Papers collection at MHS and the published Papers of Robert Treat Paine. The Massachusetts State Judicial Archives also holds records on this case, including the above indictment. Paine’s notes for this case and the indictment will be printed in full in volume 4 of the Papers, forthcoming from the MHS Publications Department in 2017 thanks to a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC).

*Quoted from the Massachusetts Judicial Archives, Suffolk Files 153487. All other quotations are from Paine’s trial notes at the MHS.