By Anna J. Clutterbuck Cook, Reader Services

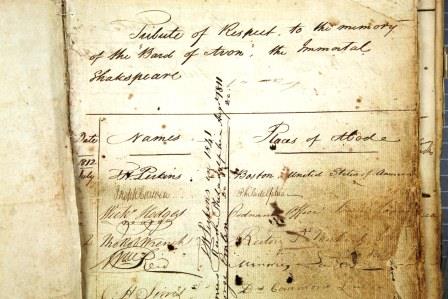

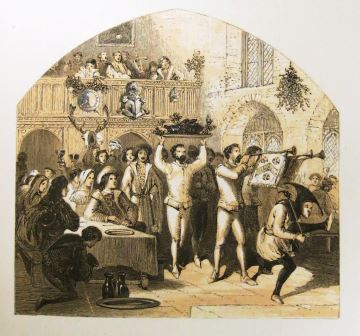

Messianic Era (1919) by John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). Boston Public Library.

Today, we return to final month of 1916 in the line-a-day diary of Margaret Pelham Russell (1858-1924). You can read previous installments here:

January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November

The final month of 1916 ends on a quiet and rather somber note for Margaret Russell. She remains close to home and although she enjoys a regular schedule of social calls and cultural events she also struggles with a “bad throat” and worries about the health of an ailing friend Mrs. Hodder. Interspersed with notes about botany lessons and concerts and club activities is the terse notation, “Paper says Germany suggests peace.” The newspaper was reporting on a public offer to negotiate made by Germany and her allies in early December. The war would continue for almost two more years until the armistice of 11 November 1918 finally brought an end to the fighting.

Margaret spent Christmas Eve and Christmas Day at charity events — a tree at the House of the Good Samaritan on the 24th and another at Massachusetts Eye & Ear infirmary on the 25th. She attended church services both days and dined with family and friends.

The day before New Year’s Eve, Margaret Russell goes down to the Boston Public Library at Copley Square to view the latest murals painted by John Singer Sargent, works that would eventually become part of his piece Triumph of Religion (1890-1919). “Messianic Era,” depicted above, is one of the ten sections installed in 1916.

* * *

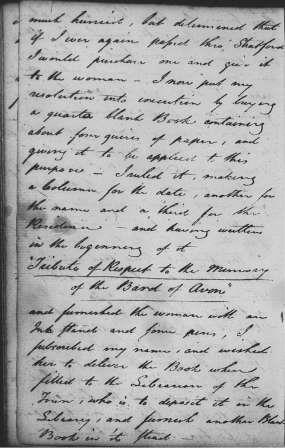

December 1916*

1 Dec. Friday – Church. Errands. Took a drive & paid some calls.

2 Dec. Saturday. The H.G.C’s went with me to Worcester to see Art Museum & lunch at the Bancroft. Nice day.

3 Dec. Sunday. Church – took walk with Georgie. Lunched H.G.C’s. Mr. Woods came to see me. Family to dine, all but Nellie who is ill.

4 Dec. Monday – Hosp. Meeting, Mary, lunch with Marian. First botany lesson then walk with Miss A–.

5 Dec. Tuesday – First Friday Club Meeting. Left early & went to hear Morton P. lecture. Walked home with F. P.

6 Dec. Wednesday – Went out to see Steve[illegible] & then a few other calls. Throat suddenly hurt me.

7 Dec. Thursday – First meeting of lunch club here. Felt poorly & stayed at home.

8 Dec. Friday – Had Dr. Smith who says I have a bad throat & took culture. Feverish & uncomfortable.

9 Dec. Saturday – Better but ready to stay on couch. Throat clearing.

10 Dec. Sunday – Better but not feeling like myself. Family to dine.

11 Dec. Monday – Still in the house but improving. Raining hard. Botany lesson. Fine day.

12 Dec. Tuesday – Raining hard. Dr. came for last time. Paper says Germany suggests peace.

13 Dec. Wednesday – Went out to dine & glad to be out.

14 Dec. Thursday – Chilton Meeting, walked home. Lunched early & went to Swampscott. Old stump has fallen.

15 Dec. Friday – [illegible], errands in the morning & to see Aunt Emma. Fine concert. Edith lunched & went with me.

16 Dec. Saturday – Errands, quite deep snow. Broke mud guard. To see the The Great Lover with Annie & Horatio.

17 Dec. Sunday – Church – lunched at Mr. Chapin’s with the H.G.C’s & Dr. Bigelow & Mrs. Sears. Family to dine.

18 Dec. Monday – C.D. Meeting where Nellie P. was elected. Lunched at Mariners. Botany lesson & did not go out again.

19 Dec. Tuesday – Went to the Bazaar for the first time. Tuesday Club met here.

20 Dec. Wednesday – Errands – Mrs. W’s lecture. Went to Swampscott & Nahant with bundles.

21 Dec. Thursday – Meeting at South End – lunch club at Jennie’s.

22 Dec. Friday – Wonderful concert! Light symphony with chorus & Paderewski (Schumann Con.) Frances P. went with me.

23 Dec. Saturday – Lunched at Edith Wendell’s. Delivering presents.Cold & windy. Wonderful concert with Paderewski. Mrs. Sears went.

24 Dec.Sunday – Church. Lunched at H.G.C’s. Tree at Good Samaritan at 4.30 & service. Miss Ahler went. Family to dine.

25 Dec. Christmas. Tree at E. & E. Infirmary at 10. Beautiful service at the Cathedral afterwards. Lunched with Marian, dined at C’s.

26 Dec. Tuesday – Mary – Miss Harmen came to play. Out to see Aunt Emma & to Mabel Walker’s tea – to see Lyman children.

27 Dec. Wednesday – Raining & freezing. Walked downtown for errands. Mrs. Ward’s lecture. Lunched at club. So slippery I stayed P.M. at home.

28 Dec. Thursday – Went to Sampscott. Easy going & not cold.

29 Dec. Wednesday – Snowing & high wind – errands for a little while & then home for the rest of the day – dined with Mrs. Sears & went to the theatre.

30 Dec. Saturday – To see new Sargent pictures at the Library – out to S. Framingham to see Mrs. Hodder who is quite ill & I am worried about her. Cold.

31 Dec. Sunday – Miss A– went to the Cathedral with me. Lunched at H.G.C’s. To call on Perrys. Family to dine but only three.

* * *

I hope you have enjoyed this year in the life of Margaret Pelham Russell. If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original.