The Importation and Sale of Enslaved People

~John Saffin, 12 June 1681

The first documented reference to the sale of enslaved people in Massachusetts is in the journal of John Winthrop (the founder of Boston), who recorded on 26 February 1638 that the Massachusetts ship Desire had returned from the West Indies carrying "some cotton, and tobacco, and negroes, etc., from thence..." (Dunn et al, eds., Journal, 1996, p. 246). Massachusetts and Rhode Island were the principal slave trading colonies in New England, and Boston was one of the primary ports of departure for ships carrying enslaved people. The ownership of enslaved people was significant economically in Rhode Island where there were sizable plantations using enslaved labor. In Massachusetts, the ownership of enslaved people probably was of limited economic importance except in Boston where craftsmen used enslaved people in their trades, but the shipping and sale of enslaved people out of Boston was much more significant. The height of this practice in New England is generally considered to be during the period 1740-1769.

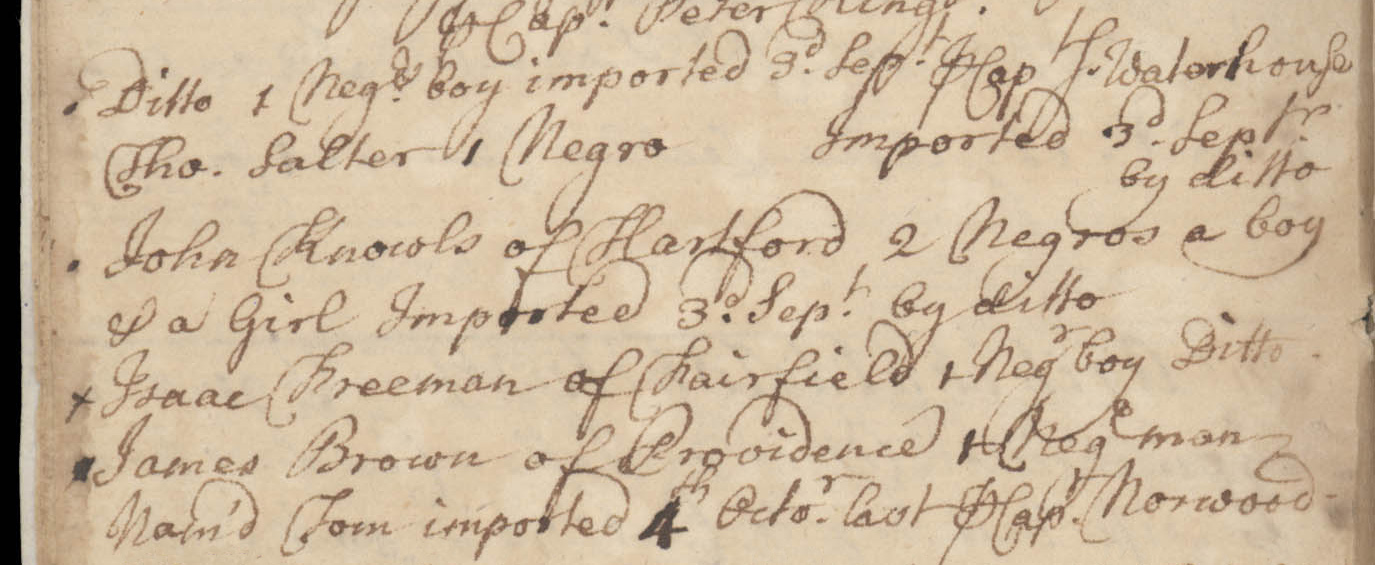

Hugh Hall account book, 1728-1733

Hugh Hall account book, 1728-1733

In 1644 Boston merchants began importing enslaved people directly from Africa, selling them in the West Indies, and bringing home sugar to make rum, initiating the so-called triangular trade. From 1672-1696 the British Parliament granted the Royal African Company a monopoly. Yankee merchants avoided the monopoly by smuggling enslaved people in through small coastal harbors. In 1681, John Saffin and other Boston merchants wrote to the shipmaster William Welstead, warning him that the authorities planned to seize a ship carrying enslaved people heading for Rhode Island, and that he should intercept the vessel and direct it to Nantasket to offload its human cargo. In 1696 the British Parliament revoked the monopoly held by the Royal African Company, enabling Massachusetts merchants and shipmasters to engage freely in the trade of enslaved people.

Colonial governors in the eighteenth century were specifically forbidden to assent to any law laying duties on or discouraging the trade of enslaved people (Greene, p. 24). There were some attempts to regulate or even to eliminate it, but most were ineffective or of short duration. A miscegenation act of 1705-1706 included a £4 import duty on enslaved people brought into the colony, but an owner could recoup his expenses if an enslaved person were sold out of the colony within a year, or if they died within six weeks of import. It has been argued that this act, rather than curtailing the practice of selling and trading enslaved people, was simply a revenue-raising endeavor for the colony (Greene, p. 56).

Hugh Hall, originally from Barbados, was a wealthy commission merchant in Boston who carried on a significant trade with his island homeland, part of which involved importing people from Barbados to Boston. His account book for the years 1728-1733 contains pages (pp. 5, 6, 8, 9, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 34, 35, 36) with entries concerning enslaved people and their purchasers. Hall often noted when people he enslaved died, or were sold out of the province, probably so that he could recover the costs of import duties.

Other, heavier duties were proposed at various times through the eighteenth century, but they were either voted down, or took effect for only a year. For example, a 1767 bill (March 1767 manuscript copy, April 1767 manuscript copy) to impose a duty of £40 on the importation of enslaved people into Massachusetts, was "unanimously non-concurred" (voted down) in the House.

Featured Items

Letter from John Saffin, John Usher, and others to William Welstead, 12 June 1681

Letter from John Saffin, John Usher, and others to William Welstead, 12 June 1681

Act for imposing a duty on the importation of enslaved people into Massachusetts (draft), [20 March] 1767

Act for imposing a duty on the importation of enslaved people into Massachusetts (draft), [20 March] 1767

Act for imposing a duty on the importation of enslaved people into Massachusetts (draft), [April 1767]

Act for imposing a duty on the importation of enslaved people into Massachusetts (draft), [April 1767]