The Lives of Individual African Americans in America before 1783

~William Park's account of expenses, 15 November 1682

In New England, where the climate and the soil were not particularly favorable for large-scale agriculture, the population of enslaved people remained smaller than elsewhere in the British colonies, but slavery did exist in Massachusetts from 1638 (Dunn, p. 246), if not earlier. Enslavement was part of the fabric of British Atlantic culture. Merchants and tradesmen owned enslaved people as a source of unpaid labor, but families of means also employed enslaved people as domestic servants. The sale of an enslaved woman named Dido in 1737 illustrates this point. The transaction involved Habijah Weld (a minister), and William Clark (a physician), two of the leading citizens of Attleboro, both Harvard-educated, and one of them (Weld) was even known for his antislavery sentiments (Colonial Collegians). By the eve of the Revolution, approximately 5,250 Black people were living in colonial Massachusetts, with the highest concentrations in important trading towns like Boston and Salem (Greene, p. 320).

The Written Record

Sometimes a bill of sale or a receipt are the only evidence we have about the life of a particular enslaved person, and even those documents often provide little insight. At this remove, the researcher can only speculate on the details of people's lives. For instance, a bill of sale for an enslaved man named Boston Loring, sold to Benjamin Williams of Roxbury in 1774 by Benjamin Dolbeare of Boston, contains little information about Loring himself. The document is endorsed on the back as a "manumission," or formal release from slavery. It is unclear if Loring was freed as a result of this sale, or whether the endorsement is just a clerical error. In contrast, the 1752 will of Catherine Cornwell is an unusual glimpse into the life of this particular free Black woman living in Boston, as it lists her children and the executor of her estate, providing evidence that she owned property to leave to her heirs.

Bill of sale signed by Benjamin Dolbeare as administrator of the estate of Nathaniel Loring to Benjamin Williams regarding Boston (an enslaved person), ...

Bill of sale signed by Benjamin Dolbeare as administrator of the estate of Nathaniel Loring to Benjamin Williams regarding Boston (an enslaved person), ...

Will of Catherine Cornwell, 8 February 1752

Will of Catherine Cornwell, 8 February 1752

Enslaved people in Massachusetts usually lived with their owners, and had more direct contact with family members than the way of life we associate with plantation slavery in the West Indies and later in the American south. The Massachusetts courts recognized the right of enslaved people to hold and dispose of some property, to keep wages for work done not on their masters' time, to bring suit in court, and the right to jury trials, legal counsel, and some legal protection. While enslaved people were generally taxed as property, they were also considered to be people by the legal system. Cuffee and Quoma, two enslaved people living in Boston, were indicted in 1748 with their white, female accomplice for a series of household robberies. One of the indictments named two other enslaved people as witnesses to the crime. The written record suggests that the three alleged criminals were treated in the same legal manner, at least initially.

The diversified New England economy allowed African Americans to participate in a variety of occupations: domestic service, farming, skilled and unskilled labor, maritime trades, innkeeping, catering, and other small industries. When a 13-year-old enslaved boy named Bodee was sold by a Charlestown tanner to a Groton blacksmith, he may have been purchased to be an apprentice, as he would have been at the right age to learn the smithing trade. Enslaved people in poor health, who were unable to work, were considered a burden. Towns passed legislation to avoid fiscal responsibility for the unemployed, the elderly, and the infirm, both enslaved and free. Clearly, it was in an owner's interest to sell an enslaved person who was sick for any price, even five shillings, as evidenced by the sale of a man named Robin in 1747 by William Clark (the Harvard-educated physician) to Ebenezer Griggs. The bill of sale was endorsed as an "indemnification," or a formal release to Dr. Clark from fiscal responsibility for Robin's care.

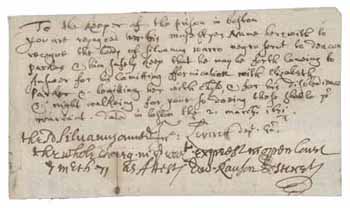

Account of William Parke’s expenses relating to Sylvanus Warro, 15 November 1682

Account of William Parke’s expenses relating to Sylvanus Warro, 15 November 1682

Instructions to the prison keeper regarding Silvanus Warro's imprisonment, 2 March 1672

Instructions to the prison keeper regarding Silvanus Warro's imprisonment, 2 March 1672

Daily life of African Americans was controlled through legislation. A 1703 law forbade Black people, Native Americans, and people of mixed race from venturing out after 9:00 p.m., unless on an errand for a white enslaver. There were other laws governing curfews, marriage, shopping, ownership of livestock, travel, and trade. "Unruly" people could be punished by the law, like Sylvanus Warro, indicted in 1672 on charges of nightwalking, disobedience, and fornication. Warro subsequently escaped from his enslaver, who filed a complaint in 1682 to recover expenses accrued in Warro's behalf. Enslaved people could also be sold out of the province, like the woman named Mindoe, who was sent down to North Carolina in 1753 on consignment for a wealthy Boston merchant. Jeremy Belknap, who accumulated historical information on slavery in Massachusetts to answer queries posed by St. George Tucker, believed that enslaved people in New England were sometimes sold to work as agricultural laborers on southern plantations as a form of punishment. (See page 14 of Jeremy Belknap's manuscript draft answering St. George Tucker's queries about slavery.)

Featured Items

- Deed from Habijah Weld to William Clark for sale of Dido (an enslaved woman), 17 January 1736/7 [1737]

- Bill of sale signed by Benjamin Dolbeare as administrator of the estate of Nathaniel Loring to Benjamin Williams regarding Boston (an enslaved person), 1 June 1774

- Will of Catherine Cornwell, 8 February 1752

- Warrant for the arrest of Ann Grafton, Cuffee, and Quoma, 12 July 1748

- Deed from Benjamin Bancroft to William Lawrence for Bodee (an enslaved person), 10 July 1728

- Indenture from William Clark to Ebenezer Griggs regarding Robin (an enslaved person), 24 October 1747

- Instructions to the prison keeper regarding Silvanus Warro's imprisonment, 2 March 1672

- Account of William Park's expenses relating to Silvanus Warro, 15 November 1682

- Receipt and agreement from James Dalton signed by Thomas Prince, relating to sale of Mindoe (an enslaved person), 24 October 1753

- Note from Edward Hewes to Dinah Keeth, 25 May 1777