By Heather Rockwood, Communications Associate

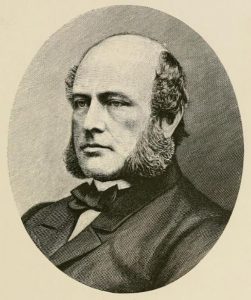

Known to her friends and family as “Clover,” Marian Hooper Adams was born in Boston, 13 September 1843, to Robert W. Hooper, an eye doctor, and Ellen (Sturgis) Hooper, a poet and a Transcendentalist. Clover and her two older siblings were raised by her father after Ellen died of tuberculosis when Clover was only five.

Clover married historian and writer Henry Adams, great-grandson of President John Adams, in 1872. They moved to Washington in 1877, where Clover was known for her wit and celebrated salon. She took up photography in 1883 and her work as a portraitist and landscape photographer was admired within her social circle. Although asked to publish some of her photographs, she declined.

After seeing Clover’s amusing portrait of her dogs Possum, Marquis and Boojum in “Three Dogs at Tea in Garden” recently, I wondered if she had an affinity for taking photographs of dogs. And the answer is yes!

Although her main subjects were mainly landscapes or portraits of her friends and family in various settings, dogs made it into these portraits ten times out of the one hundred and thirty seven photographs held in the MHS collection. In her two and a half year career as a photographer from 1883-1885, seven percent of her photographs contain dogs!

Her favorite dog to include in her portraits was Marquis, who appears in five of the ten portraits, although Boojum with three and Possum with two portraits are close runners up. What I find most fascinating about Clover’s dog portraits is their clarity. Portraiture in the 1880’s was becoming easier for the subject, as exposure, or sitting, time was down from minutes to seconds. But it could still have been up to 64 seconds depending on the time of day, year, and lens used on the camera. These long exposure times lead photographers to ask their subjects to sit very still or they must choose to take pictures while their subjects naturally repose, or rest. After viewing many of Clover’s portraits, it is clear she preferred mainly the latter and you can see why in this image of a young boy and dog in front of a windmill.

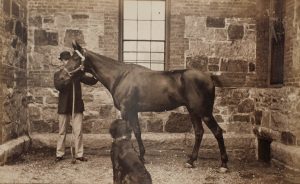

A blurred image shows the movement of the subject during the exposure time while a photograph was taken. And in this image where Clover took a photograph while Brooks Adams, her brother in law, was caring for a horse shows some very specific blurring.

You can see that the dogs would need to be specially trained to stay still for up to 64 seconds, which Clover may have achieved. Or the dogs may be used to being in repose with their human companions. I especially enjoy the images that look as if Clover captured a moment between the human and dog where they are relaxing with each other.

This portrait features Boojum at the feet of James Lowndes, a friend of the Clover and Henry Adams.

Marquis playing with Henry Adams, Clover’s husband.

Dandy can be seen here relaxing while Betsy Wilder, beloved housekeeper from Clover’s youth, knits on a porch.

In the images which appear more staged, rather than at rest, you can see that the dogs are upright and either looking at the camera, or looking at their human companion.

This image is from a glass plate negative, displayed in positive as the printed portrait is much more difficult to see. The subject of this portrait, Boojum, is seen quite clearly at the feet of Mrs. Jim Scott, a neighbor who came along for a day at the beach.

Toto and Marquis are seen here comforting Miss Langdon, who is in mourning attire for her recently deceased grandmother, on the same porch steps which we saw Marquis playing with Henry.

Marquis is seen here relaxing, perhaps after a brisk walk, with James Lowndes. This may have been on the same day as the other image with James Lowndes.

Natalie Dykstra writes in her biography Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, “If Clover could be playful and mocking in her pictures, as with her “dogs at tea” photograph, a send-up of social convention she occasionally found tedious, she could also evoke sadness or an intense feeling of loss.” I do feel that although the subject of dogs can be whimsical, especially for photography in the 1880’s, that their human companions mostly evoke sadness.

The second and last in Clover’s “dogs at tea” series features Marquis and Possum. This one has a more natural setting and no white backdrop giving the image a feeling that the viewer happened upon this tea party that was already occurring.

To read more about Marion “Clover” Hooper Adams and her photography visit the MHS online Collection Guide, see the MHS Selected Letters and Photographs, or read The Beehive blog post about those pages and the biography by Natalie Dykstra.

Further Reading:

Letters Shed New Light on Henry Adams | Beehive (masshist.org)

Clover Adams’ Memorial: From a Husband Who Would No Longer Speak Her Name – Atlas Obscura