By Lauren Howard, Adams Papers Intern

“The Accounts We have of the Uneasy State of the Minds of our Countrymen: their innumerable Projects, and fluctuating Politicks are perhaps more distressing to Us, than they are to you who are on the spot… For my own Part I am too old and feeble, to fight— They must put me to death for my neutrality: for I will not be a Party Man.”

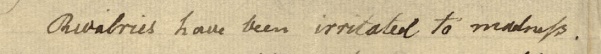

Despite his disdain for party politics, John Adams’s administration began with the country already divided along party and regional lines. He narrowly won the presidency by three electoral votes, although he entered office with a distinct advantage—a Federalist majority in Congress. This majority allowed a bill to be introduced and quickly signed into law. For example, the Nonintercourse Act of 1799 was introduced in the Senate on 1 March 1799 and signed two days later; “An Act to Lay Additional Duties on Certain Articles Imported” was introduced in the House of Representatives on 8 May 1800, passed and transmitted to the Senate later that day, and signed by Adams on the 13th. Despite this Federalist majority, congressional records reveal that it was also a period of increasing partisan polarization and conflict. During my internship with the Adams Papers editorial project, I used the Adams Papers Digital Edition, Annals of Congress, and the House and Senate Journals to construct a legislative calendar of the important bills passed during the Adams administration. Bill by bill, my research revealed the gradual entrenchment of party divisions. “Rivalries have been irritated to madness,” Adams wrote to Abigail Adams in February 1799, and this madness even erupted in a physical altercation in the House.

A prime instigator of this increased factionalism was the breakdown of diplomatic relations with France. In December 1797, Abigail Adams correctly foretold, “Should we be forced into a war, which God forbid, parties would again assume a face of violence.” After initially urging diplomatic restraint and voicing a dedication to “keep the Peace with their high Mightinesses at paris,” Adams called on Congress to create a navy to protect the coast and commerce of the United States. In the wake of the XYZ Affair, the nation was consumed by war hysteria but found itself split over the French issue. Democratic-Republicans called for a de-escalation of tensions and a halt to war preparations, while Federalists passed numerous bills to prepare the country to fight. “An Act to Provide for an Additional Armament for the Further Protection of the Trade of the United States” and “An Act for the Establishment of the Department of the Navy” passed in the Senate by large majorities and little effectual resistance from Democratic-Republicans.

Members of the House also voted along party lines on related issues. The Sedition Act passed on 10 July 1798 by a vote of 44 to 41, with 21 abstentions. All of the yes votes came from Federalists, although three crossed party lines to oppose the bill. Later, the Sedition Act was used exclusively to arrest and imprison Democratic-Republicans.

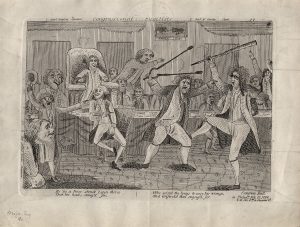

The ongoing conflict with France reinforced the party lines drawn several years earlier with Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality. As factionalism divided Congress, partisan conflict evolved beyond balloting and policymaking. On 15 February 1798, a brawl—complete with a walking stick and fireplace tongs—broke out on the House floor. On 30 January 1798 Federalist Roger Griswold insulted Matthew Lyon’s valor during the American Revolution, after Lyon declared himself a champion of the common man and accused Griswold of corruption. Lyon, a Democratic-Republican from Vermont, spat at Griswold and was charged with gross indecency by House Federalists. However, as an outraged Abigail Adams wrote, “Instead of considering what was due to the Honour of the House, as Legislatures and as gentlemen, they have sufferd narrow party views to operate.” With Federalists unable to secure enough votes to remove Lyon, Griswold took matters into his own hands and beat Lyon with his cane; Lyon defended himself with fireplace tongs. The men later apologized and retained their seats, but the incident provides valuable insight into party conflict during the Adams presidency. The fight was instigated by disagreements over Adams’s militaristic approach to Franco-American relations and debates over which party better served American interests. According to Abigail Adams, the affair also “created more warmth, more wrath more ill will, than the most momentous questions of National concern.” Thus, while Adams despised party politics, his administration further established party identities and fostered partisan conflict so intense that it erupted in legislative violence.