By Alex Bush, Reader Services

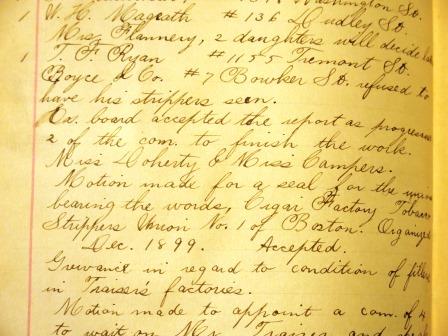

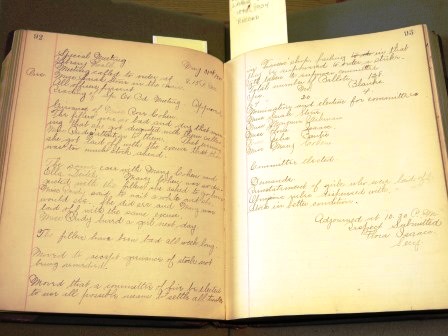

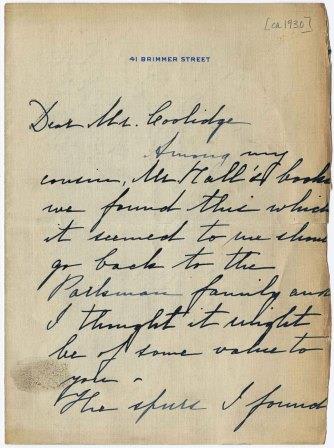

The Pemberton collection, a compilation of materials from several New England families connected by marriage, includes a few artifacts from Mary Channing Eustis of Milton, Massachusetts. A dedicated recorder of recipes and what we now lovingly refer to as “life hacks,” Eustis filled two commonplace books with directions for the making of everything from plum cakes to stomachache cures. After recently rediscovering Emilie Haertsch’s 2012 blog post on Ben Franklin’s milk punch (http://www.masshist.org/blog/838), I figured another experiment with a vintage recipe was long overdue. Should this post instill you with further curiosity about Massachusetts’ cooking-related past, consider attending the MHS public program series “Cooking Boston.” The next installment (2 of 6) is scheduled for the 27th of April.

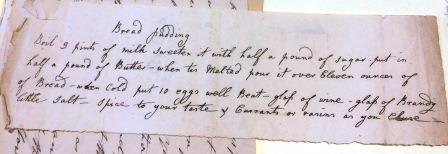

With that, let us explore Mary Channing Eustis’ recipe for bread pudding. Since I’d been planning to attempt a bread pudding anyway, I was quite excited to find this recipe. To my untrained eye it looked like the perfect choice—easy, simple, and delicious.

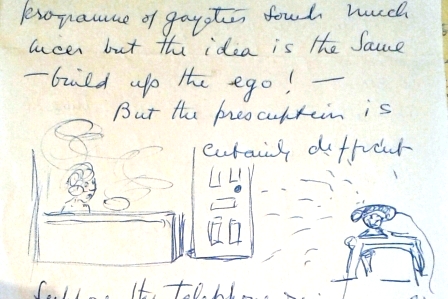

“Boil 3 pints of milk sweeten it with half a pound of sugar put in half a pound of Butter – when tis melted pour it over Eleven ounces of [of] Bread – when cold put in 10 eggs well Beat – glass of wine – glass of Brandy little salt – spice to your taste & Currants or raisins as you Choose—”

The photo and transcript above represent the recipe in its entirety. It is vague at best, with some decidedly odd proportions. In order to accommodate my lack of a kitchen scale as well as my unwillingness to sacrifice 10 eggs, I halved the recipe and converted each measurement into its approximate equivalent in cups. Pictured below is the full array of ingredients as well as a bag of flour, which I was almost positive the recipe included despite having read it multiple times. Milk was also included in the recipe, but is not pictured here. Obviously the baking nerves were already setting in.

First, Eustis indicates that the milk should be boiled and sweetened with sugar. However, due to her disinclination toward comma usage, I was unsure whether she meant that the sugar should be added right away or after the milk was boiled. I was also unsure as to whether boiling milk is ever a good thing to do. Instead, I put the milk in a pot over medium heat and brought it to just before boiling, adding sugar gradually until it dissolved. As the milk heated, I chopped the bread into cubes (despite the recipe not specifying that I should do so) and put it into a bowl. After this, the recipe calls for an off-putting amount of butter to be melted into the milk before the whole mixture is poured over the bread.

“Speak softly and melt a big stick of butter.” -Theodore Roosevelt, (Historical note: Theodore Roosevelt did not, in fact, say this.)

Honestly, this was the recipe at its best. You might as well stop reading right here. Even so, at this point my sweetened bread and dairy concoction was likely pretty far from what Mary Channing Eustis would have had. I used skim milk, while Eustis almost certainly would have used whole milk or even cream, considering the fact that skim milk was not sold in U.S. stores until around World War II. The same goes for the overall differences in quality between my Stop n’ Shop rolls and whatever delicious, probably homemade bread Eustis had on hand. I am also fairly certain that Eustis had never heard of Craisins, which I added later on.

A festival of health.

Eustis’ recipe instructs that the above mixture should chill before the next steps can be taken. While chilling, my bread absorbed most of the milk mixture and became incredibly soggy. This made the next step in the recipe especially painful. To the bread and milk, the (halved) recipe instructs that five well-beaten eggs must be added. This made the eggs to milk ratio almost equal, creating what can only be described as a sweet, uncooked bread omelet.

There are no words.

The recipe then calls for one glass each of wine and brandy. Nowhere is it specified how much a “glass” is supposed to be, so I estimated by adding half a standard-sized wine glass of each. At this point, I figured, adding a little alcohol would only make things easier for everyone. I also added a few handfuls of Craisins to substitute for currants, and spiced the pudding “to my taste” with vanilla, nutmeg, cinnamon, and a pinch of salt. All in all, the uncooked pudding did not look half bad. It looked fairly similar to other bread puddings I’d seen previously, and the spices and wine made it smell quite lovely! With nothing in the recipe indicating how long or at what temperature the pudding should be baked, I was forced to guess. I cross-referenced a few other bread pudding recipes and came up with 350 degrees for 40 minutes. With an inflated sense of optimism, I placed the pudding into the oven to bake.

Before.

After.

Admittedly, the pudding looked very handsome at the end of its bake. My apartment was filled with the fragrant scents of cinnamon and butter, the top of the pudding was beautifully brown, and it appeared that most of the liquid had been absorbed. However, the sheen of butter grease coating the surface did not inspire confidence, nor did the fact that my first spoonful of the pudding revealed a pale and wobbly interior beneath the crust. The sad result of this experiment was a bread pudding that resembled a sweet frittata more closely than anything else. The spices, sugar content, and baking time were spot on. Had the proportions been slightly more even, this probably would have turned out well. However, the sheer amount of butter and eggs in this recipe coupled with the comparably small amount of bread made for a greasy, breakfasty mess.

There are many reasons why this could have turned out as badly as it did. First of all, Mary Channing Eustis likely compiled this book of recipes for herself, her family, or her peers. All of those people undoubtedly had some background in the cooking techniques needed for these recipes, including knowledge of typical oven temperatures or a sense of how many eggs is too many eggs. Second, as I mentioned before, it was impossible to recreate the dish with complete accuracy given the supplies, skills, and hardware I had on hand. Finally, it may just be the case that eggy puddings were in vogue back in the 1840s and 50s, and that this egg purgatory was inescapable. While I personally cannot see the appeal, Eustis obviously could, given the fact that this book is absolutely full of similar recipes. Any avid egg-eater is welcome and encouraged to attempt this recipe and share the outcome.

Despite the eggy result, this was a fascinating experiment and a great look into an older take on a still-popular dish. I certainly look forward to revisiting Eustis’ recipe book for more questionable recipes in the future. Perhaps I’ll look into her home cure for an upset stomach first.