By Rakashi Chand, Reader Services

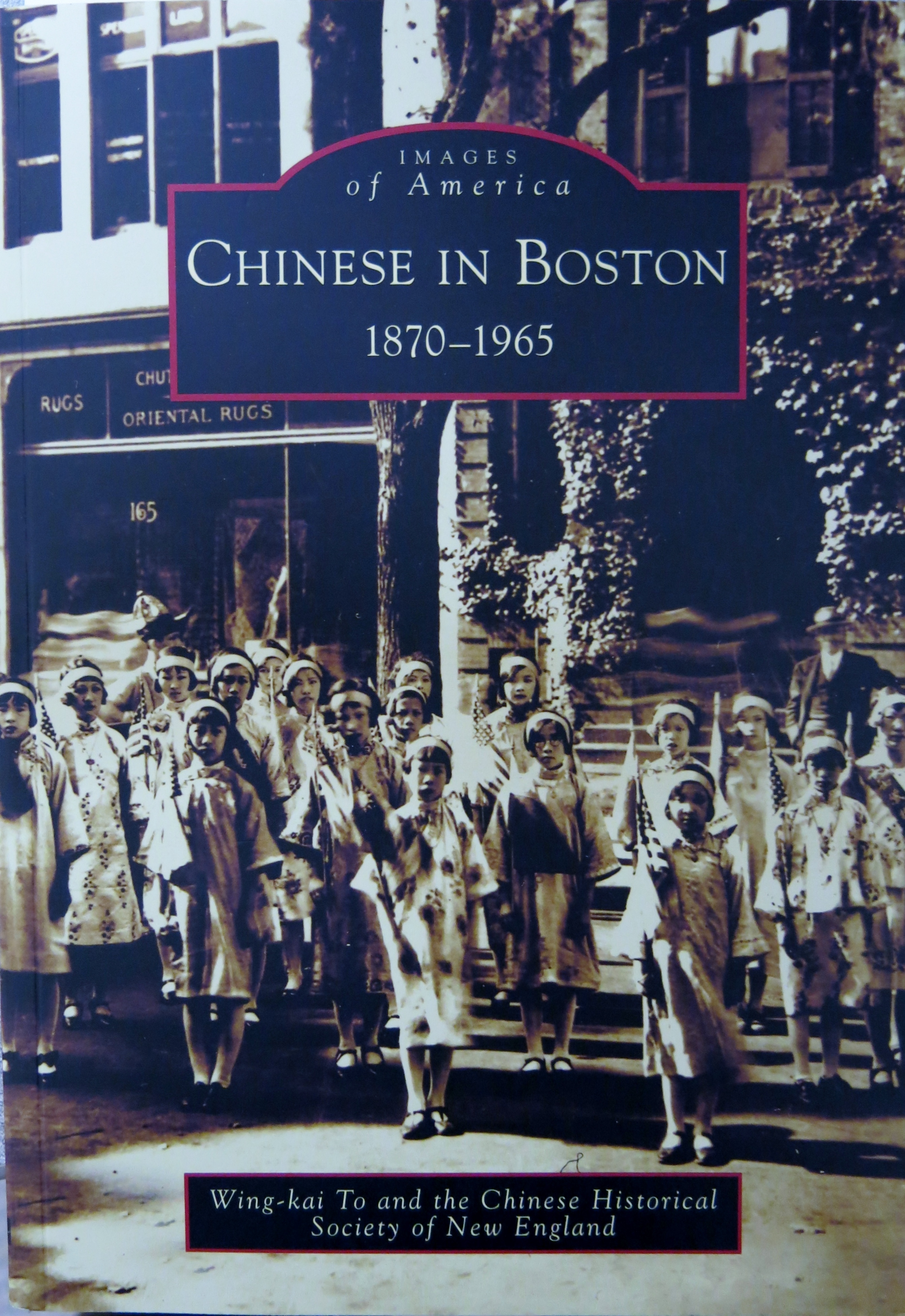

Chinese in Boston, 1870-1965 by Wing-Kai To and the Chinese Historical Society of New England (Charlestown, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), part of the Images of America Series, tells the story of the Chinese experience in New England with a focus on Boston, MA through historic photographs with captions. The book is divided into seven chapters, which range from the first arrivals of Chinese immigrants in New England to the Settlement of Boston’s Chinatown, to various other topics until finally arriving at the modern experience of the Chinese in Boston. The text is brief as the photographs are the main source of history and context in this book.

The images come from a variety of sources ranging from the Bostonian Society to the Peabody Essex Museum to the Chinese Historical Society of New England, which was founded in 1992 to document the coherent and vibrant culture of Chinese Americans in New England. The book features the first Chinese owned business, notable members of the Chinese community, and photographic evidence of cultural assimilation as well as cultural preservation carried out in New England. The photographs are well presented and illustrative of the Chinese American experience in New England.

This book is useful for people trying to familiarize themselves with the Chinese history in New England and due to its length and format, can be read/viewed easily and quickly. It is hard to research the history of immigrant groups or minorities who were often not affluent and therefore not the subject of art, photography or historical records, making this book a rare source of an under-represented topic of New England History. This book begins circa 1870 with the first (known) photographic evidence of Chinese immigrants in New England and concludes with present day imagery.

Related Collections:

For more general history of Chinese immigrants in America the library of the Massachusetts Historical Society offers there secondary sources:

The Chinese in America: A Narrative History by Iris Chang (New York: Viking, 2003).

Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 by Roger Daniels (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988).

Nothing Like It in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, 1863-1869 by Stephen E. Ambrose (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

For the Chinese Exclusion Act we offer:

The Chinese Exclusion Act, Known as the Geary Law: Speech of Hon. Elijah A. Morse, M.C., of Massachusetts, in the House of Representatives, Friday, October 13, 1893 (Washington : [s.n.], 1893).

Amendment of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Speech of Hon. William Everett, of Massachusetts, in the House of Representatives, Saturday, October 14, 1893 (Washington: s.n., 1893).

Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East: A Cultural Biography by Da Zheng; foreword by Arthur C. Danto. New Brunswick (N.J. : Rutgers University Press, 2010).

An Anglo-Chinese calendar for the year …: corresponding to the year for the Chinese cycle era (Canton : Office of the Chinese Repository).

Circular letter, signed C. L. Woodworth, regarding the Associations efforts with Chinese immigrants, Indians and African Americans. [Boston : s.n., 1880]

The library of the Massachusetts Historical Society houses a rich collection of China Trade papers and resources:

“Manuscripts on the American China trade at the Massachusetts Historical Society” by Katherine H. Griffin. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, v. 100 (1988), p. 128-139.

Researchers on site also have access to the Adam Mathew database of primary source materials China, America and Pacific: Trade & Cultural Exchange.