Deciphering Political Cartoons

Political symbols, racial and ethnic stereotypes, personification of ideas, and caricatures of once familiar public figures abound in 19th-century political cartoons. Early in the century, cartoons usually depicted static figures espousing now-arcane political points—and sometimes dreadful puns—in text-filled balloons. Later in the century, cartoons are filled with once-familiar political symbols and caricatures of public figures whose likenesses have faded from popular memory. Racial and ethnic stereotypes also are very common, even in cartoons that express sympathy for the plight of the people or causes represented in them. While some political symbols—such as the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant—have remained remarkably stable over time, Thomas Nast’s characterization of “Boss” Tweed as a bloated money bag on legs may elude present-day viewers. Explore a selection of cartoons that illustrate some of these elements with brief explanations to help you “decipher” images found throughout the web display.

"A National Game that is Played Out," political cartoon, engraving by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 23 December 1876, page 1044.

Thomas Nast drew this cartoon of a ballot box being kicked about as a reference to the contested 1876 Hayes-Tilden presidential election which was decided by an Electoral College commission, rather than the popular will of the voters.

The 19th-century ballot box was a hand-blown glass bowl contained in a frame to make voting “transparent.” It was an attempt to eliminate ballot box stuffing, but it became a ubiquitous symbol in political cartoons for voting rights or, as in this case, the abuse of voting rights.

Personification

Political cartoonists have relied on personification—giving human characteristics to non-human objects and ideas. Over time, figures once frequently caricatured have become less familiar and stock characters in cartoons have been superseded.

"The 'Brains.' That Achieved the Tammany Victory at the Rochester Democratic Convention," political cartoon, engraving by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 21 October 1871, page 992.

“Pardon Me, Mister—Do You Know What Time It Is?”By Herb Block--- Published August 27, 1946 Credit line: A 1946 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation

At the culmination of his epic crusade against “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Ring, Thomas Nast reduced his repeated caricatures of Tweed to their essence: he portrayed the driving force—the “Brains”—behind political corruption in New York as Tweed’s body with his face replaced by a money bag. In 1871, Nast could use this artistic shorthand to great effect, as Tweed’s enormous girth and his “radiating” diamond pin would be familiar to readers of Harper’s Weekly.

Seventy-five years later, Herblock (Herbert Block) personified the danger of the nuclear age in the character of “Mr. Atom”—an early atomic bomb with human features. In July 1946, only weeks before Mr. Atom asked “World Diplomacy” what time it was, the U.S. had conducted atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. While Block did not intend Mr. Atom to be a continuing figure in his cartoons, this character made many appearances and became even more ominous with the proliferation of nuclear weapons during the Cold War.

Stereotypes

Political cartoonists have and continue to make use of stereotyped characters. A stereotype is a visual shorthand for identifying individuals or groups. However, once easily understood references to supposed religious or ethnic attributes can be hard to understand or be deeply offensive to today’s viewer. Nineteenth- century cartoons often contain negative racial stereotypes. This is true even in cartoons that promote civil or political rights, no matter what the intention of the cartoonist.

Thomas Nast’s progressive views on civil rights and good government were marred by an extraordinary hostility to Irish immigrants (almost always shown as the dupes or violent supporters of the Democratic political machine) combined with an equal or greater anti-Catholic bias.

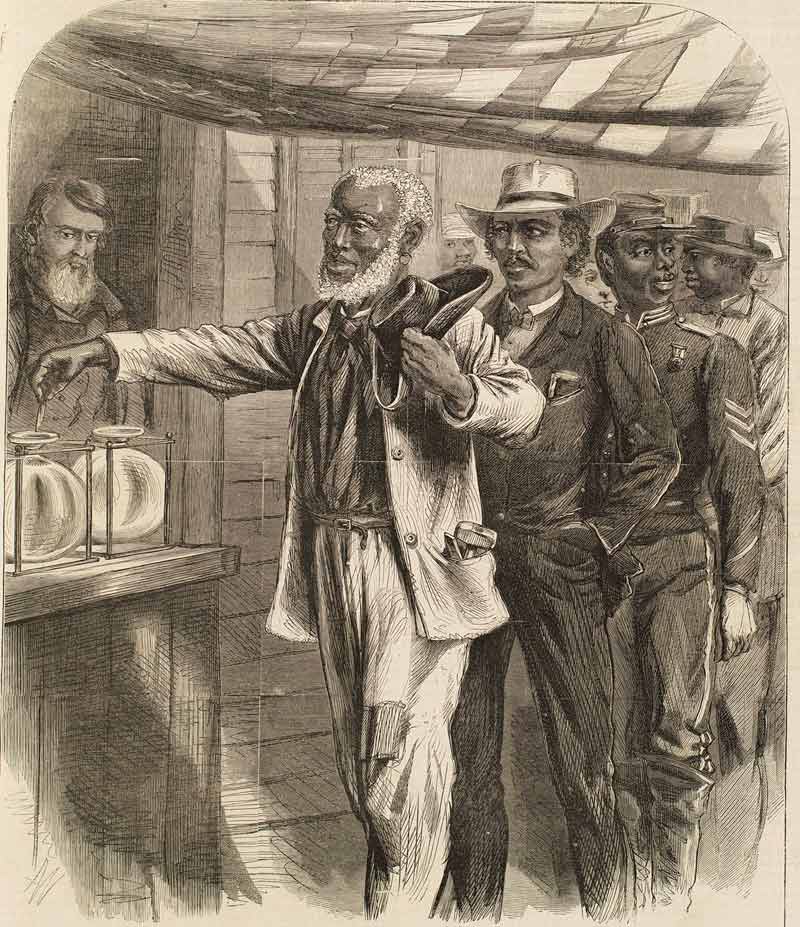

This cover illustration for Harper’s Weekly was drawn by Alfred R. Waud. Born in London, Waud became a celebrated Civil War artist/reporter who documented Black life in the South during Reconstruction. Here he depicts “representative” Black men casting ballots for the first time, including an aged laborer in patched clothing, a sharply attired businessman, and a former sergeant still wearing his Civil War uniform.

In 1871, “borrowing” from a drawing by the English illustrator and political cartoonist, John Tenniel, Nast protested Irish immigrant rioting in New York. He drew a simian-featured Irishman sitting on a powder keg with a rum bottle in one hand—and a lighted torch in the other.

Complicated Cartoons

The illustrations below are examples of how odd early political cartoons can appear today. They often contain static figures making long statements contained in balloons above their heads or, even more mysteriously, include little or no explanatory text. Almost all early cartoons require close examination and, even then, the subject matter can remain elusive.

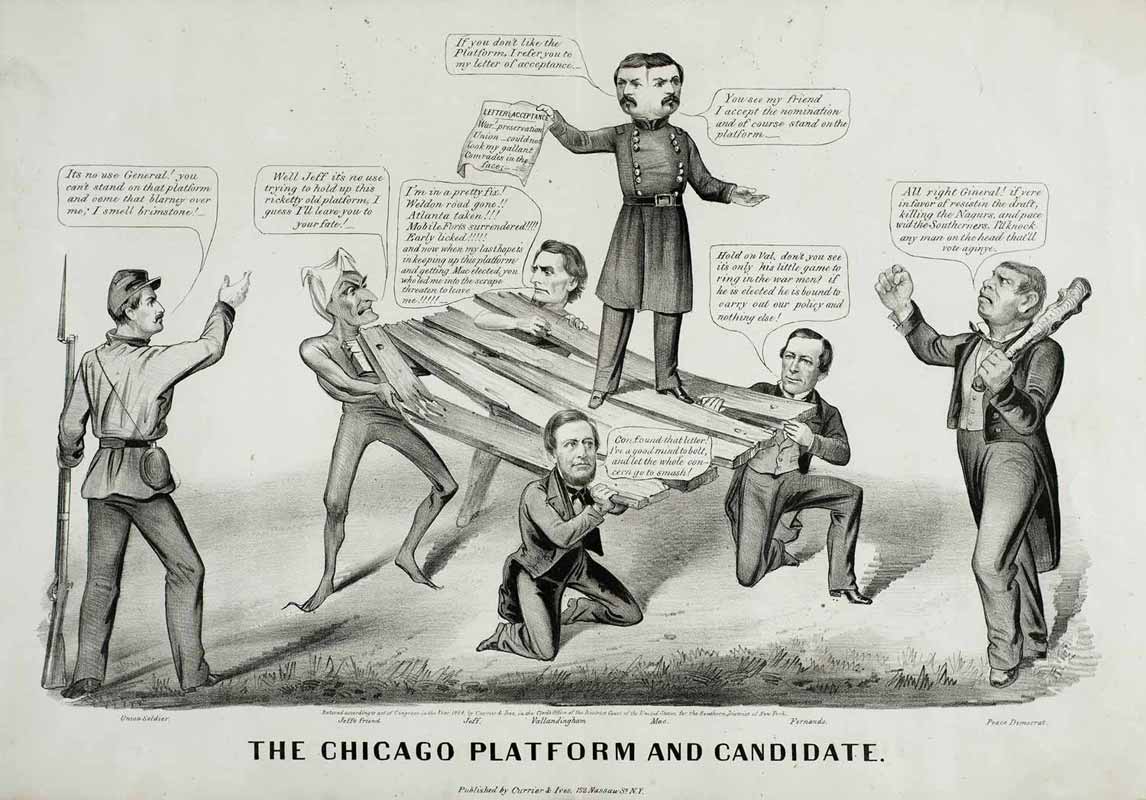

The Chicago Platform and Candidate, Lithograph. New York: Currier and Ives, 1864

Hypocritical general George McClellan, attributed to Louis Maurer, is shown here as literally two-faced: he vows to run for president in 1864, both to keep faith with his fellow Union soldiers and as a peace candidate. He stands upon the shaky Democratic Party platform proclaimed at the Chicago convention, held up at the front by Copperhead politicians Fernando Wood and Clement L. Vallandigham, and at the rear by the devil and Jefferson Davis. A patriotic Union soldier on the left “smells brimstone,” while an Irish immigrant “Peace Democrat” (armed with a club and speaking in dialect) threatens to “knock any man on the head that’ll vote agin” McClellan.

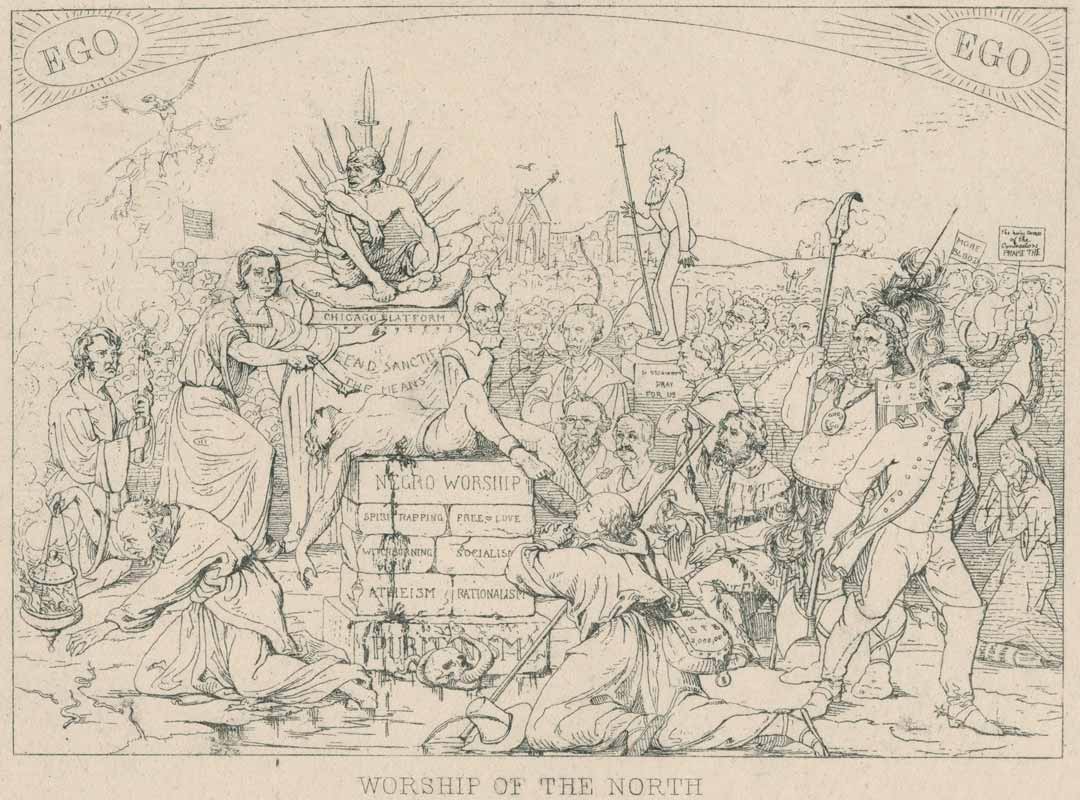

Adalbert J. Volck, a Maryland dentist, drew satirical, pro-Confederate attacks on Union hypocrisy and inept leadership in his cartoons, such as Worship of the North. Photography made it possible for Volck to draw fair likenesses of the Union political figures and soldiers that he caricatured. While it is difficult to know how widely Volck’s cartoons circulated during the war, reprints of them became popular among Southern sympathizers in later years.

In Worship of the North, Volck satirizes a “Chicago Platform” diametrically opposed to that drawn by Louis Maurer—the Republican Party Chicago platform of 1860—as “Negro Worship.” Under the gaze of Abraham Lincoln and lighted by a torch held by Charles Sumner, Henry Ward Beecher sacrifices a chained white man on the altar to a Black slave as Union generals who pressed for emancipation, Benjamin F. Butler and John C. Fremont (in buckskins), look on from the right. John Brown stands on a pedestal armed with a pike—the enslaved people he hoped to lead in revolt were to be armed with pikes—and Harriet Beecher Stowe looks on from the right-hand margin of the cartoon. The altar rests on “Puritanism” and is labeled with a somewhat incoherent list of the moral failings of the North, including “free love” and "socialism” along with “atheism” and “witch burning.”

This cartoon is from a set of lithographic facsimiles of Volck’s Civil War etchings printed in Philadelphia in about 1886.

"The First Vote," political cartoon, engraving drawn by A. R. Waud. From Harper's Weekly, 16 November 1867, page 721.

"The First Vote," political cartoon, engraving drawn by A. R. Waud. From Harper's Weekly, 16 November 1867, page 721.