By Alex Bush, Reader Services

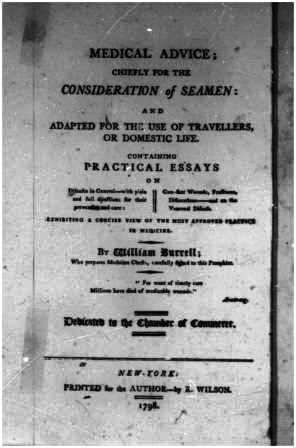

With flu season fast approaching and many coworkers and peers already succumbing to illness, the time has come to consider our health and safety for the wintry months ahead. What can we, “the enterprising Mariner—the hardy Soldier—the industrious Citizen,” do to mitigate “the direful consequences of infection?” William Burrell, a late-1700s seller of special medicine chests designed for sailors, collaborated with several physicians to create a pamphlet designed to adapt his sailors’ medicine chests for use by the common citizen. It contains page upon page of useful advice on treating anything from the common cold to gunshot wounds. Note that while William Burrell may not have been an actual doctor, his expertise in preparing medicine chests was definitely enough to qualify him to publish medical advice.

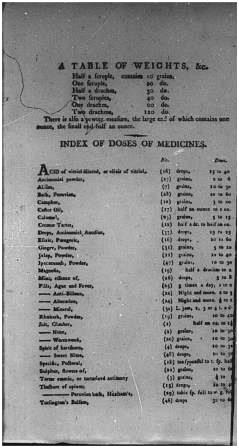

Published in 1798, Medical advice; chiefly for the consideration of seamen: and adapted for the use of travellers, or domestic life can be found within the MHS’ Evans microfiche collection of Early American Imprints. Within this pamphlet Mr. Burrell describes dozens of maladies common during the late 18th century with an eye toward prevention and quick recovery via home remedy. Burrell acknowledges that, shy of “devising and applying means to destroy the Fons et origo mali, (fountain and origin of evil,) and restore the purity of the atmosphere in which the patient breathes,” the best practice for combating illness is to keep the patient clean and comfortable. Most of this is achieved by way of steam, hot water, and a combination of chemicals. Although it is unlikely that Burrell’s medicine chests are still on the market today, the pamphlet fortunately includes a compilation of names and suggested doses for most of the medicines mentioned. Simply visit your local pharmacy for everything listed except, perhaps, tinctures of opium.

In general, Burrell warns that cold climates as well as rapid changes in temperature can predispose one to sickness. The same is true for excessive drinking of beer and spirits, so take care to stay sober during any upcoming holiday parties. Should you find yourself becoming ill, restrict your diet to bland foods such as gruel, pasta, oysters, and boiled meat. Those who remain healthy should bolster their diets with “sallads,” which are “saponaceous, detergent, cooling, and antiseptic,” as well as “opening and diuretic.” However, Burrell warns that salads should be avoided if one feels cold or nervous.

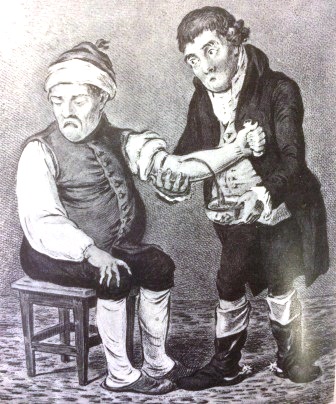

Lithograph showing a phlebotomy, London 1804, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

In terms of cold symptoms, Burrell’s advice varies according to diagnosis and outside conditions. Most of it, however, involves bloodletting. Bloodletting (or bleeding) was a popular method of treatment for a wide range of ailments from the 1600s into the 1800s, after which it slowly declined in popularity. According to Burrell, bloodletting is an especially necessary step when the climate is cold. For fevers, intersperse repeated bleedings with induced vomiting. For coughs, bleeding and periodic doses of tincture of opium are recommended. In order to prevent malaria while vacationing in warmer areas, remove a pint of blood to account for the change in temperature and allow yourself to sweat freely.

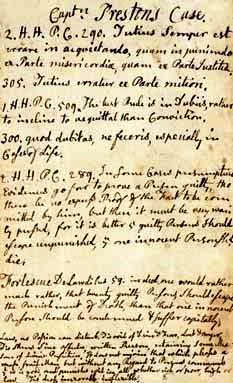

Bear in mind, however, that a footnote to Burrell’s pamphlet warns against the dangers of excessive bloodletting:

it is of the utmost importance not to reduce the system by bleeding or any other evacuation whatever, below the ordinary healthy standard, as a firm constitution and a chearful and fearless mind, most powerfully resist the sedative action of pestilential contagion.

“Life of George Washington: The Christian,” lithograph by Claude Regnier, after Junius Brutus Stearns, 1853. Washington Library, Mount Vernon, VA.

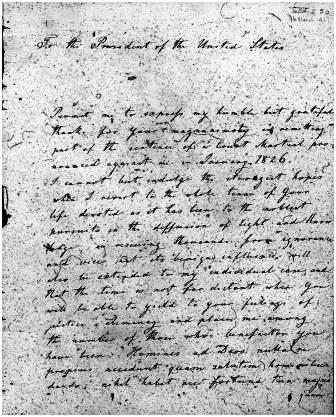

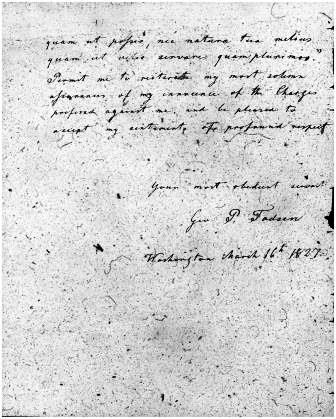

Recall, for instance, the circumstances under which George Washington died. In December of 1799, after spending most of the day supervising his Mount Vernon farm in freezing rain and snow, the former president refused to remove his wet clothing for dinner. Naturally, the next day he developed a sore throat. Spending another full day outside in three inches of snow only made his sore throat worse, and by the following morning he was terribly ill and having trouble breathing. Attended by three physicians and his wife, Washington was given a mixture of molasses, vinegar, and butter to soothe his throat. A firm believer in the healing power of bloodletting, he also asked that half a pint of blood be removed from his arm while refusing other medicines and treatments. “You know I never take anything for a cold,” he said. “Let it go as it came.” As his condition worsened over the next ten hours, an estimated total of two and a half quarts of blood were removed from Washington’s body, amounting to over half of the blood in his body. He passed away at 10 p.m. on Saturday, December 17, 1799. Take care to remember this story while treating your own cold-weather ailments using bloodletting.

Chemicals in the form of gargles, tinctures, and skin treatments are also popular cures in Burrell’s pamphlet. According to Burrell, most oils and tinctures work best when dissolved in plain water or “common nitrous drink,” which can be made by dissolving a few grains of nitre in water. Add citrus juice, molasses, or vinegar to aid in digestion and soothe the throat. Bodily aches and pains caused by influenza or infection can be remedied using a blister, a paste made from mashing a special type of “blister beetle,” to draw toxins to the surface of the skin. The blistering toxin found in blister beetles has been used medically as a vesicant- an agent that causes blistering – as well as an aphrodisiac since the 12th century BC. Use it well, but do not eat it—you will almost definitely die.

With Burrell’s expert and up-to-date advice in mind, venture forth into this year’s cold season without fear!

References

Burrell, William, Medical advice; chiefly for the consideration of seamen: and adapted for the use of travellers, or domestic life, (New York: Printed for the author by R. Wilson, 1798).

“The Death of George Washington,” Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 2017, accessed on 30 November 2017, http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/the-death-of-george-washington/

Vadakan, Vibul, MD, FAAP, “The Asphyxiating and Exsanguinating Death of President George Washington,” The Permanente Journal 8, No. 2, Spring 2004, accessed on 30 November 2017, http://www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/Spring2004/time.pdf.

Schmidt, Justin, “Cantharidin and Meloids: a review of classical history, biosynthesis, and function,” 2002, accessed on 30 November 2017, http://archive.li/Srh6y.