by Neal Millikan, Series Editor for Digital Editions

Transcriptions of more than 700 pages of John Quincy Adams’s diary have just been added to the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary, a born-digital edition of the Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The new material spans the period January 1789 through August 1801 and chronicle Adams’s experiences as a law student in Newburyport, a young lawyer in Boston, and a diplomat in the Netherlands and Prussia.

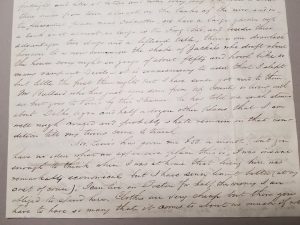

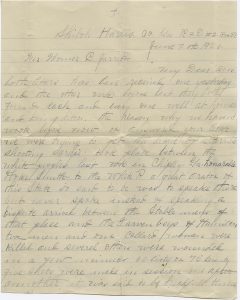

“My present situation is not over eligible: how to improve it is the subject which most employs my mind,” Adams wrote on 7 April 1791. “I have much leisure upon my hands, and my own improvement seems to be the proper object of my pursuit,” although he questioned his own “egotism” as he tried and failed to faithfully keep his journal. Adams had completed his legal studies under Theophilus Parsons in Newburyport the previous July and was been admitted to the Massachusetts Bar. Choosing to establish his office in Boston, the 23-year-old struggled to gain ground professionally even as he began to find his political voice.

In the summer of 1791 Adams responded to Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man with a series of articles under the pseudonym “Publicola.” The following year brought pieces by “Menander” opposing the state anti-theater ordinance, and in late 1793 and early 1794 he earned recognition for his “Columbus” and “Barneveld” series, commenting on the behavior of the Antoine Charbonnet Duplaine, the French consul at Boston, and Edmond Genet, the French minister to the United States.

These activities found favor in Federalist circles. In May 1794 President George Washington nominated John Quincy Adams as minister resident to the Netherlands. It was the first of four diplomatic postings Adams held. He and his youngest brother, Thomas Boylston Adams, who served as JQA’s secretary, arrived at The Hague in late October. During an errand to London in 1795, John Quincy met Louisa Catherine Johnson, the daughter of U.S. consul Joshua Johnson and Catherine Nuth Johnson. After more than a year’s courtship, the couple married in London on 26 July 1797 and soon departed for John Quincy’s new diplomatic post at Berlin, where the minister successfully negotiated a new Prussian-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1799. Neither John Quincy nor Louisa relished the demands of court life with its lavish social engagements. Louisa’s frequent ill health during these years weighed on John Quincy, and he noted his feelings in his diary. After Louisa had several miscarriages, she gave birth to their first son, George Washington Adams in April 1801, shortly before John Quincy received his recall and the family returned to the United States.

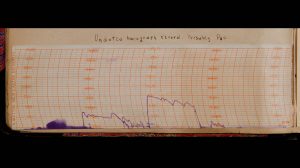

For more on John Quincy Adams’s life during these years, read the headnotes for his early legal career and early diplomatic career, or, navigate to the entries to begin reading his diary. The addition of material for the 1789–1801 period joins existing transcriptions of Adams’s diary for his years as secretary of state (1817–1825) and president (1825–1829) and brings the total number of transcriptions freely available on the MHS website to nearly 4,000 pages. Thanks to MHS web developer, Bill Beck, the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary also now includes side-by-side viewing capability. By choosing the “transcription + image” dual mode, users can view the transcription alongside the manuscript image; or, they can still view the transcription alone. This dual-mode option appears at the top of each entry. Check it out! And let us know what you think. The tool is still in its beta phase, and we welcome user feedback. You can reach us at adamspapers@masshist.org.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary is provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund. Harvard University Press and a number of private donors also contributed critical support.