By Sabina Beauchard, Reader Services

On a rainy Sunday, March 29, 1908, Robert A. Boit of 19 Colchester Street, Brookline sat down to write in his journal after a lapse of around 3 weeks. One of the happenings he reported on was a local murder-suicide that made newspapers across the nation. Boit had a personal connection to it all; he wrote:

On Wednesday morning the 11th of this month a terrible tragedy took place in the Girls Boarding School on Audubon Road facing the Fenway. The two principals of the school Elizabeth Hardee and Miss Weed were killed. Elizabeth was the daughter of my dear old friend Pearson Hardee of Savannah and on that account I was brought into immediate touch with the whole affair. [emphasis added] My letter to Hardee, here in my journal, tells the story so I will not repeat it. Poor Hardee himself came on from Savannah himself to settle up matters and I was glad to be of some assistance and comfort to him, for he was terribly shaken. He arrived on the 21st and remained four or five days. We wanted him to come directly to the house, but he decided that in his condition of mind he had better stay at the St. Botolph Club, where I put him up. But he took many of his meals with us, and I think being with us really did him good. It was a tragic affair and in a lovely spot.

In between journal pages, Boit tucked in a typescript of the letter he mentions sending to his grieving friend William Pearson Hardee on March 15. By the 15th, Boit already sent word alerting Hardee to the incident, but one letter was chosen by Boit to save for posterity; the letter reproduced below.

I will follow Boit’s sentiments and let his letter to Hardee speak for itself:

[handwritten] The Story of a Tragedy –

Brookline, March 15, ’08.

My dear Pearson:

No doubt you got my last letter and telegrams, and I received your telegrams. I have tried each day to write you, but have been so interrupted I could not do it.

Last Wednesday afternoon, after writing you, I went to the Undertaker’s to whom the Coroner had sent Elizabeth’s body, and arranged for all that at that time could be done, and thence to Dr. Joslin’s [Elliott Proctor Joslin] who was a friend of Elizabeth and had been called to the house at the time of the tragedy. There I met the brother-in-law of Miss Page [Katherine R. Page] – one of the teachers who lived in the house and seemed to have the most authority. His name was Alexander. We three talked the matter over, and decided that the house should be closed at once, that no extra expense might be incurred, and that the teachers might not in any way be held responsible for further orders for the maintenance of the house or its service. To this end Mr. Alexander wished me to go to the school that night and talk matters over with the teachers still living in the house, Miss Page, Miss Chase and Miss Hamilton. This I did, and was with them till half past ten arranged matters. I also got in communication by telephone while there with Dr. Stedman [George Stedman], the Coroner, who was legally in charge of and responsible for everything in the house. I got him to authorize the Teachers to pack up the silver, and a small locked tin box, which he promised to have taken to the safety vaults the next morning, and this was done. There was very little money found in the house or in this tin box which was opened by the officer later. I think, with the two checks, this amounted to less than thirty dollars. The teachers had sent off the pupils that very day, Wednesday, and had sent most of the pupils’ things with them. They also agreed to pack such things of the pupils as still were left and mark the packages with the pupils’ names and leave them in their various rooms. This they did on Thursday before they left the house.

We also found that night (Wednesday) that the servants wages had all been paid up to the preceding Friday, and as it seemed to me you would not wish the servants discharged without their wages, I agreed to send Miss Page the money for this purpose the next day. As the servants had to be retained on Thursday to help pack up and clean and wash, it made a week’s wages due them and in two or three instances two weeks. The amount due was just $51.47, for which Miss Page took their separate receipts, and sent me the statement, which I enclose. The teachers said they were under the impression from what Elizabeth had said, that she was having a hard time to meet her expenses, and that there were probably a good many bills unpaid.

[page break]

Of course, this cannot be clearly ascertained until the administrator has been appointed, of which I will speak later.

That evening they told me clearly all the circumstances leading to the end, and they were very harrowing. All the teachers and pupils had gone to bed very early that evening except Miss Page, as they were up late the night before. At about half past nine in answer to a ring at the door, Miss Page let in Miss Weed, who had run away from the Sanitorium at Newton. She said she knew she should not have come, but begged that it was so late she should be allowed to pass the night. Miss Page said she had not seen her before so reasonable and quiet and dispassionate and was much impressed by the fact that she consented to let her stay, took her upstairs, prepared a room for her, lent her her own nightgown and dressing gown, and then sat with her till quarter past twelve chatting. She seemed entirely normal and made herself most agreeable and interesting, talking of the school and its interests and almost not at all of herself.

When she left her she thought of locking her door and then decided it best not to. During their talk Miss Weed had agreed to get up early and take the half past seven train home, so that no one should be disturbed or know she had been there. Miss Page was to get up early and give her her breakfast. No one else knew that she was in the house. Miss Page left her own door open and tried to keep awake and listen but no doubt fell asleep. At about three she heard noises and got up and went to Miss Chase’s or Miss Hamilton’s room where she thought she heard voices. There she found these two in great terror. Miss Hamilton had been wakened by hearing some sound at her door. She got up and found a note thrust under it. In her sleepiness she glanced at it without reading it and thought Elizabeth wanted to speak to her, and went to her room and asked. But Elizabeth said no, she had not sent for her. So rather bewildered, she shut Elizabeth’s door and returned to her own room. Then she read the note for the first time and discovered it was from Miss Weed, and upbraiding her with being false to her charge, etc. She was much frightened, knowing now that Miss Weed must be in the house, and at once went to Miss Chase’s room and waked her. It was this Miss Page had heard, and she found them together and much distressed. While all three were talking in Miss Chase’s room, (first, however, Miss Page had tried three times without success to get the Sanitorium by telephone) they heard a tapping at their door, but by the time Miss Page got there, Miss Weed who had knocked, had run towards Elizabeth’s room. Miss Page, knowing that of late a feeling had grown in Miss Weed’s mind of hostility to Elizabeth, followed immediately and went into Elizabeth’s room, where Miss Weed was standing back of the door. She immediately explained everything to Elizabeth who was entirely calm and tranquil, even tho’ awakened under such circumstances at 3 o’clock at night. Miss Page said her self-control was extraordinary. She talked quietly and dispassionately to Miss Weed, telling her how unwise and thoughtless it was of her to come there and disturb their sleep when they were all so tired, etc, and

[page break]

arranging, as Miss Page has done, that she should go back to Newton early in the morning. Miss Weed said very little, tho’ she seemed rather frightened, but was soon quieted by Elizabeth and appeared, as she always did with Elizabeth, to be entirely under her influence.

Before she left the room, she heard Elizabeth say – “Why, Susan, (if that was her name), you have not taken down your hair. Take it down and come to bed”. Then she left them and went again to her own room, but left the door open and did not sleep again. This was at about half past three perhaps.

After this all was quiet in the house and at a little before six she got up and dressed. In fact, I think she said that before this, at five or half past, she went to their room, and found them sleeping peacefully, side by side. She went softly to the bed and laid her hand gently on Miss Weed, who did not wake or show any signs of being awake. Afterwards, at a little before six, she dressed as I have said, and at a quarter past six went to their room again to wake them, saying “as Miss Weed was going, it was time for them to get up and that meanwhile she would go down stairs and get some coffee and eggs ready for them”. Elizabeth was lying on her back, and had answered rather drowsily – “Thanks, Miss Page, that’s very nice. We will get up at once”, or words to that effect.

Then she went out of the room into one or two other rooms, and in less than three minutes heard two pistol shots. She rushed to Elizabeth’s room and found them both shot through the head, Elizabeth with her face towards the wall shot through the back of the head, and Miss Weed shot through the temple and with the pistol in or near her hand. Miss Page immediately called for Dr. Joslin, who arrived there within fifteen or twenty minutes and found them both dead.

This dear Pearson, is the exact story as told me Wednesday night by Miss Page and the other teachers, chiefly by Miss Page, who of course had known so much of what had happened.

After leaving the house that night, I went again to Dr. Joslin’s and talked over matters with him. The next morning I arranged with the Undertaker [Frederick L. Briggs] (this was Thursday morning) who had then received his papers from the Coroner, permitting him to send away the body, for everything regarding the shipment, and in the afternoon went there to see that all had been properly done. I saw poor Elizabeth and thought her looking very lovely, with such a quiet, peaceful expression on her face. I do hope every arrived as it should have. If you had seen that face as I did, without one sign of sorrow or suffering in it, with just the gentle restfulness of sleep, I think it must have been a help and consolation to you in your sorrow.

Friday morning I went to the School and found it has been closed entirely as agreed on Thursday, and that the Coroner had put a man in charge who was to pass day and night there until otherwise ordered by him. Friday noon a Mr. Samuel W. Child, Lawyer, 43

[page break]

Tremont St., Boston, came to see me and told me that at the request of Dr. Stedman (the Coroner) the Court had appointed him as Temporary Administrator and made him responsible for everything; that he must examine everything at the house, get together all account books, check books, etc., bills and anything else of value that might be found there. He was most anxious that I, as a friend of yours, should go there with him for this purpose. So I consented and passed several hours at the School with him that afternoon. It was very hard to do it, but I felt you would rather have me there than think of a strange man doing it alone. Indeed it seemed sacrilege and made my heart ache to its depths, and only the thought of you and how I should myself have felt under these circumstances enabled me to do it.

There was little of value among the personal effects, but we concluded from the unpaid bills we saw, that it was most unlikely that the assets would pay the liabilities. I think, my dear friend, there is little doubt the school will prove insolvent. There was a balance at the First National Bank of some six hundred dollars, and it is possible there may be a balance in a Newton Bank in which there appears to be a deposit – how much could not be learned yesterday.

Then there is the furniture of the house, which was bought of the Paine Furniture and by contract was to have been paid for in full on the first of February. This so far as we could judge has not been done. There was an unpaid bill dated the first of this month for either nine or eleven hundred dollars for the draperies of the house. There are two pianos of Chickering, which the teachers seemed to think had not been paid for. There seemed to be some large bills for fuel and food unpaid, etc. Also I learned that there was a considerable amount claimed by the teachers for their salaries, and there is a long lease of the house at $1,000. each quarter. I think the lease runs for 5 years.

Against all these claims, the assets seen to be the $600. at the First National, such balance as there may be in the Newton Bank, the books and such of the furniture as had been paid for. Beyond this there only remain a few little trinkets of Elizabeth’s, her clothes, the linen in the house and the silver. As to this latter, I suppose, unless it could be very clearly proved to belong to some one else, it would have to be held as part of the assets. No doubt if it were sold at auction for this purpose by the Administrator, it could be bought in at a small price compared to its value as family silver.

The temporary Administrator, who seems to be a very respectable man, told me that he should try to get the books (account books) and papers in order and find out about how matters stood. No doubt he will let me know when he has done so, if he does it. He also told me that the Court would appoint a regular Administrator, but that it would take about three weeks to do this; that then his own duties would be at an end and everything turned over by him.

I regret that I myself am so old and worn out with my own cares and responsibilities, I could not myself accept this position, even if the Court were willing to appoint me. One other thing I forgot to mention. There may be bills

[page break]

owing by the parents of the school, but the teachers knew nothing of them, except that Elizabeth made advances to the girls from time to time. They also told me the regular charge for Tuition, etc. was $1000. per annum, but that a number paid less, owing to the fact that it was the first year of the school.

The temporary Administrator thought there would be little chance of collecting balances that might have been due, owing to the fact of the closing of the school, even if these balances could be determined. Under all those circumstances, and the almost certain insolvency of the school, I don’t know what you may determine to do, or whether it will seem wise for you or your son to incur the expense of coming here and staying a month or two to become the administrator and settle the estate, or arrange for its settlement. If you do not come, no doubt through the Administrator appointed by the Court, all will be effected that can be, and yet, of course, you may prefer to take part in it.

If I can give you any information or assistance or advice, of course, you will not hesitate to call upon me, and anything that I hear I will write you.

With a great deal of love, my dear old friend, and a heart full of sympathy, I am

Most affectionately yours,

Rob. A. Boit

By the time this letter was sent, Elizabeth Hardee’s body had taken its final journey home to Savannah, Georgia by train and had arrived on March 14. The next day, her funeral was held and she was interred in the Hardee family plot in Laurel Grove Cemetery near her mother, Cornelia, who had passed in 1896 [1]. William Pearson Hardee committed suicide in 1917 and was buried in the same plot [2].

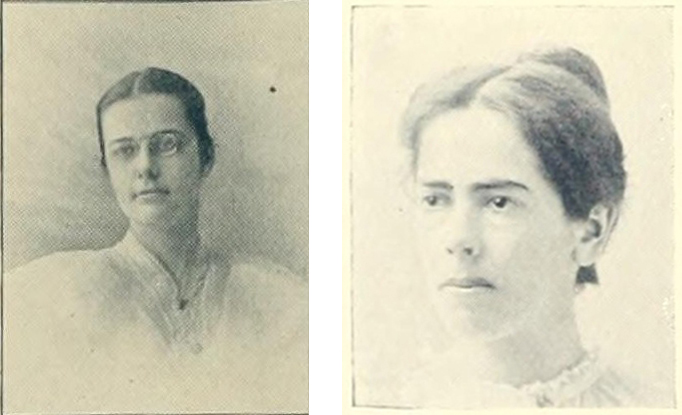

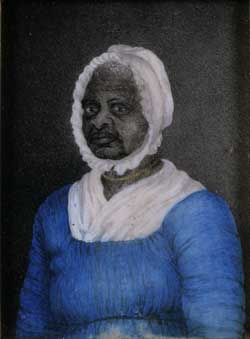

Elizabeth Bailey Hardee and Sarah Chamberlain Weed as represented in the Wellesley College Legenda, 1894 & 1895, respectively.

Elizabeth Bailey Hardee (1873-1908) and Sarah Chamberlain Weed (1869-1908) both attended Wellesley College; with Elizabeth graduating in 1894 and Sarah in 1895.

Much of the information about their activities and whereabouts before the opening of their school I gleaned from Wellesley publications; a Baltimore Sun article dated 11 March 1908; and a lengthy article on the murder-suicide in the Boston Post, 11 March 1908.

The 1899 & 1900 academic years found Elizabeth at her alma mater of Wellesley College as an assistant in mathematics [3]. Elizabeth resurfaces in Wellesley news in the winter of 1902; with both Elizabeth and Sarah listed as teachers in Mathematics and English, respectively, at Newton High School [4]. Years pass until 1906, when the two young women report as having “accepted a share in the management of Miss Chamberlayne’s School for Girls, The Fenway 28, Boston” [5]. Finally, in June of 1907 the women “announce the opening of The Laurens School for Girls, 107 Audubon road, Boston, Massachusetts” [6].

The Laurens School for Girls, the boarding school the two women brought to fruition in the Fenway, became the setting of Elizabeth and Sarah’s murder-suicide just 8 months later. According to news reports, the day the school opened to students for the first time on October 1, Sarah Weed suffered a breakdown “due to overwork.” [7]

Sarah was first confined at “Dr. Norton’s Sanitarium in Norwood”, the Norwood Private Hospital; but was transferred to “Dr. Dutton’s home for convalescents in West Newton” [8] until the night she appeared on the doorstep of the Laurens School.

The above journal entry was taken from volume 14 (1910-1912) of the Robert Apthorp Boit diaries held in the library of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Interested readers may also find letters William Pearson Hardee sent to Boit on March 16, 18, and 28, 1908, tipped into the pages along with Boit’s typescript roughly transcribed above. Learn more about using the library on our website.

Robert Apthorp Boit (1846-1919) graduated from Harvard in 1868 and shortly thereafter moved to Savannah, Georgia with his parents, and joined his father’s commission business. This is likely when Hardee and Boit met and struck up a friendship. Boit returned to Boston a married man around 1878, and became successful in the insurance business.

I hope to continue this post with what I’ve gleaned on the location of the school. Tune in later!

[1] Aiken Journal and Review, Supplement, November 14, 1917

[2] Letter from William Pearson Hardee to Robert Apthorp Boit, Savannah, 16 March 1908, Robert Apthorp Boit diaries, volume 14, tucked into page 21.

[3] Wellesley College Record, 1875-1900

[4] Wellesley News, (Vol. 1, No. 14) February 6, 1902

[5] Wellesley News, (Vol. 6, No. 1) October 3, 1906

[6] Wellesley News, (Vol. 6, No. 32) June 12, 1907

[7] The Pensacola Journal, March 13, 1908

The Abbeville Press and Banner, March 18, 1908

[8] The Sun, March 12, 1908

owing by the parents of the school, but the teachers knew nothing of them, except that Elizabeth made advances to the girls from time to time. They also told me the regular charge for Tuition, etc. was $1000. per annum, but that a number paid less, owing to the fact that it was the first year of the school.

The temporary Administrator thought there would be little chance of collecting balances that might have been due, owing to the fact of the closing of the school, even if these balances could be determined. Under all those circumstances, and the almost certain insolvency of the school, I don’t know what you may determine to do, or whether it will seem wise for you or your son to incur the expense of coming here and staying a month or two to become the administrator and settle the estate, or arrange for its settlement. If you do not come, no doubt through the Administrator appointed by the Court, all will be effected that can be, and yet, of course, you may prefer to take part in it.

If I can give you any information or assistance or advice, of course, you will not hesitate to call upon me, and anything that I hear I will write you.

With a great deal of love, my dear old friend, and a heart full of sympathy, I am