By Daniel Tobias Hinchen, Reader Services

Today, the MHS is happy to unveil a recent acquisition to the collection. On 12 July the Society announced the acquisition of a significant collection of Shaw and Minturn family papers, photographs, art, and artifacts. The most remarkable item in the collection is the officer’s sword carried by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment – the first Northern regiment composed of free black volunteers. One hundred fifty-four years ago, Shaw carried the weapon during the failed assault on Fort Wagner, Morris Island, South Carolina. With sword in-hand, Shaw was shot in the chest while mounting the parapet and was killed. The sword and other personal effects were stolen from his body during the night and presumed lost.

However, the sword survives. Following acquisition of the sword from descendants of the Shaw family, the collections staff here at the MHS had the daunting task of tracing the provenance of this sword in order to ensure that it is the genuine article.

What follows is a brief chronology of Robert Gould Shaw and his sword, as laid out by Curator of Art & Artifacts Anne Bentley, and Senior Cataloger Mary Yacovone, who combed through various sources published, primary, and otherwise. [N.B. – These events are arranged chronologically but, as with much historical research, the pieces fell together in anything but clear order.]

*****

Nov. 1860 – Robert Gould Shaw (RGS) enlists in the 7th NY Militia.

28 May 1861 – RGS commissioned 2nd Lieutenant, Company H, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry.

8 July 1861 – RGS commissioned 1st Lt. in same.

10 Aug 1861 – RGS commissioned Capt. in same.

31 Mar 1863 – RGS commissioned Major, newly-formed 54th Massachusetts Regiment.

17 Apr 1863 – RGS commissioned Colonel, 54th Mass. Regt.

[mid-late April 1863?] – RGS’ uncle, George R. Russell, orders an officer’s sword for Shaw from master English swordsmith Henry Wilkinson.

11 May 1863 – Wilkinson sword no. 12506 proofed on this date, per Henry Wilkinson records.

23 May 1863 – Wilkinson sword no. 12506 etched and mounted on this date. Sold to C. F. Dennett, Esq., per Henry Wilkinson records.

28 June 1863 – RGS wrote to his mother: “Uncle George has sent me an English sword, & a flask, knife, fork, spoon &c. They have not yet come.”1

29 June [1863] – “June 29 – Monday. “Arago” in and mail from the North.”2

1 July 1863 – RGS wrote to his father that “A box of Uncle George’s containing a beautiful English sword came all right.”1

4 July 1863 – RGS wrote to his father that “All the troops, excepting the coloured Regiments, are ordered to Folly Island. … P.S. I sent you a box with some clothes & my old sword. Enclosed is receipt.”1

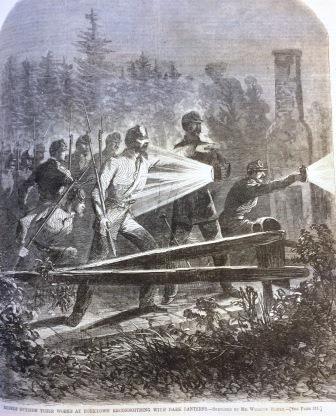

16 July 1863 – Mass. 54th participated in the Battle of Grimball’s Landing, James Island. RGS probably used his new Wilkinson sword in this action. First experience under fire for the 54th, which stood strong and proved its mettle covering the retreating Union forces.

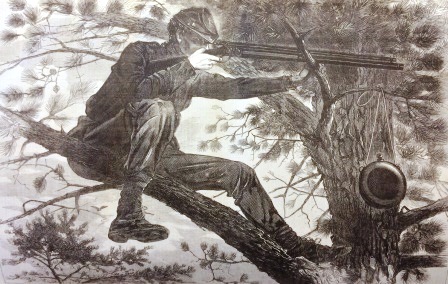

18 July 1863 – Assault on Fort Wagner. RGS shot in the chest as he stood on the parapet of Ft. Wagner, sword in hand. Overnight his body was robbed of personal effects and arms and stripped to underwear. Sources differ as to the culprits.

19 July 1863 – RGS buried. According to Brig. Gen. George P. Harrison, C.S.A. writing to Luis F. Emilio much later, RGS was placed in the rifle pits below the parapet and 20 of his dead soldiers placed on top of him. Sources here differ also.

Friday 24 [July 1863] – John Ritchie diary: “Packed up Col. Shaw’s effects & expressed them North.” Ritchie later noted that he also sold the colonel’s horse.

3 June 1865 – Letter from Brigadier General Charles Jackson Paine, district commander at New Berne, N. C., to family:

Goldsboro June 3, 1865. I heard the other day of the sword of the late Robt. G. Shaw killed at Fort Wagner, in the possession of a rebel officer about sixty miles from here. I sent out and got it; the scabbard was not with it. I am going to send it on as soon as I have an opportunity.3

28 Jan 1876 – Letter from Lydia Maria Child to John Greenleaf Whittier:

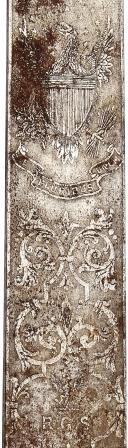

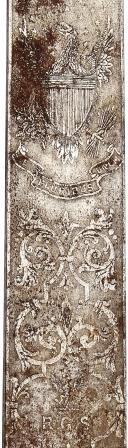

I spent last winter with the parents of Colonel Shaw…The flag of the 54th Regiment was in their hall, and the sword of Colonel Shaw. There is a history about that sword. It is very handsome, being richly damascened with the United States coat-of-arms, and the letters R. G. S. beneath. It was a present from a wealthy uncle in England, and he received it a few days before the attack on Fort Wagner […] When his mother showed me the weapon she said: “This is the sword that Robert waved over his followers, as he urged them to the attack. I am so glad it was never used in battle! Not a drop of blood was ever on it. He had received it but a few days before he died.”4

Detail of the sword, showing United States Coat-of-Arms and initials R.G.S.

(Photograph by Stuart E. Mowbray)

1900 – At a meeting of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Commandery of Massachusetts, Brev. Lt. Solon A. Carter, U.S.V., presented a paper titled “Fourteen Months’ Service with Colored Troops,” in which he stated:

In July [1865], upon leaving the service, the late Assistant Adjutant General* was charged by General Paine with the duty of restoring the sword to Colonel Shaw’s father, and upon arrival at this home, opened a correspondence with Mr. Francis George Shaw informing him of its recovery.

The sword in question proved to be the one carried by the gallant colonel and was identified by the initials R.G.S. delicately etched upon the blade. In a postscript to one of his letters, Mr. Shaw wrote, “The sword was a present to my son from his uncle, Mr. George R. Russell, who purchased it in England and caused the etchings to be made there.”

In a subsequent letter acknowledging its receipt he says “I thank you most heartily for all the care and trouble you have taken. So far as such words may be applied to an inanimate thing it is the weapon which has done most for our colored people in this war, and it is to me likewise as well as to you a source of great satisfaction that is was recovered and restored by officers of colored troops.”

*Captain Solon A. Carter, of Leominster, Mass., served as C.J. Paine’s Assistant Adjutant General. Appointed 15 July 1864 and resigned 3 July 1865.

Mar 2017 – The sword was found in the attic of the home of Mary (McCawley) Minturn Haskins.

6 Apr 2017 – In an e-mail to MHS Curator of Art & Artifacts Anne Bentley, one of the donors stated:

Susanna Shaw Minturn is my great-grandmother and apparently was very close to her brother, RGS. Her oldest son, Robert Shaw Minturn, had no children; there were four girls and my grandfather, Hugh Minturn (who died in 1915, before his mother). I can only guess, but presumably my great-grandmother passed the sword on to my father, Robert Bowne Minturn, not her oldest grandson, but the senior by male primogeniture. My father was 15 when his grandmother died in 1926. The sword may have hung on his childhood bedroom wall.

17 Apr 2017 – Shaw sword is given to the Massachusetts Historical Society as part of a larger gift including papers and portraits.

*****

1. Shaw, Robert Gould, Blue-eyed child of fortune: the Civil War letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw / edited by Russell Duncan, (Athens : University of Georgia Press, c1992.)

2. Lt. John Ritchie’s diary, Quartermaster of the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry Regiment, whose diary was used by Luis F. Emilio in A Brave Black Regiment.

3. Paine, Sarah Cushing, Paine ancestry : the family of Robert Treat Paine, signer of the Declaration of Independence, including maternal lines / compiled by Sarah Cushing Paine ; edited by Charles Henry Page, )Boston : Printed for the family [Press of D. Clapp & Son], 1912.

4. Child, Lydia Maria Francis, Letters of Lydia Maria Child / with a biogrpahical introduction by John G. Whittier and an appendix by Wendell Phillips, (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1883).