By Nancy Heywood

In November, the Oxford Dictionary announced that “selfie” was the word of the year for 2013. The definition of selfie (from oxforddictionary.com) is:

a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website

Selfies are very common these days. Many images show the subject looking up, into the lens, and often the subject’s arm extends out of the picture (holding the very device that captures the image). These photographs are sometimes seen as lighthearted and whimsical and sometimes seen as a sign that the world is becoming filled with self-absorbed people!

Do a couple of photographic self-portraits from the past (held within the Massachusetts Historical Society’s collections) have much in common with selfies of today? The photographic equipment and processes used in the 19th century (requiring cumbersome cameras and multiple steps: exposure, development, and printing) significantly differ from the equipment and approach of creating digital images today (captured on portable and ubiquitous devices and then often seamlessly shared with family and friends).

What about the characteristics of the self-portraits from two different eras? Selfies are deliberate but quick, documenting that one was at a place or with a person and distributed publicly, ideally seen by lots of people. 19th-century self-portraits were also deliberate but had to be painstakingly composed. Within these self-portraits, most photographers took efforts to hide the fact that they took their own pictures. Photographic self-portraits were potentially sharable; many copies of a particular image could be made from the same negative and then distributed to friends and family members.

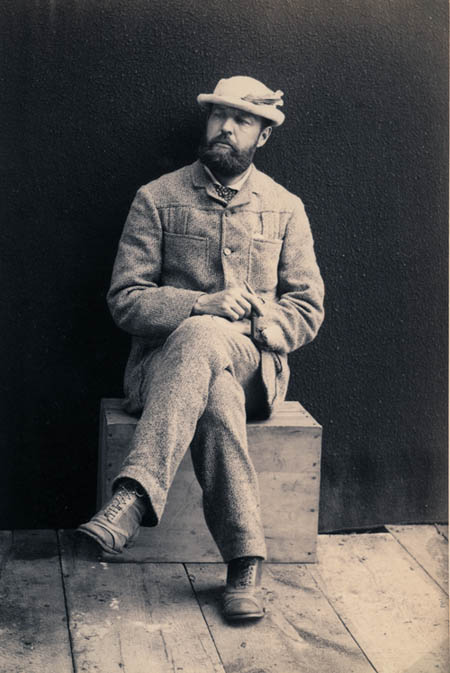

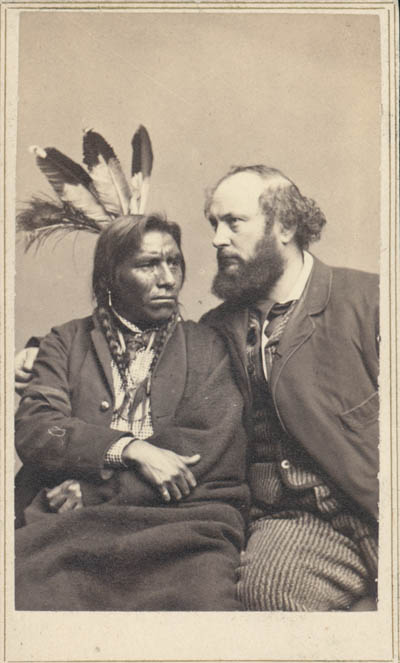

Two examples of 19th century photographic self-portraits from the collections of the MHS are a photograph taken by Francis Blake in 1885 (image below, on left) and a photograph of two men taken in 1862 by Charles D. Fredricks , who is most likely the man on the right (image below, on right). One reason why it is likely that the image on the right does include the photographer (Fredricks) is because the man on the right’s left hand extends beyond the frame of the image and could have held a remote control for the camera’s shutter. Here is one slight similarity with selfies—the arm beyond the edge of the image! However that similarity is offset by the fact that 19th century photographers tended to minimize any evidence of how they took their self-portrait whereas within selfies it is often quite obvious that someone in the picture, took the picture. Viewers have to closely examine the large digital image of Francis Blake’s self-portrait (click on the photo) to see that he holds a remote shutter release in his right hand.

The seriousness of both the 19th-century images seems to differentiate them from most selfies, but one way they are similar to selfies is the fact that Blake and Fredricks consciously put themselves in front of their cameras and took the pictures. I find Fredricks’ image of himself and the Chippewa man to be intriguing, and although it is very different from a selfie, I wish he had treated it more like a selfie by leaving a comment or answering that familiar prompt from Facebook: “Say something about this photograph…”! Fredricks’ photograph is awkward (the two men look in different directions, and Fredricks’ right arm is stiffly draped over the shoulder of the Native American) but the image seems to document a significant moment for the photographer.

Whether or not there are many similarities between 19th-century self-portraits and selfies of today, it is interesting to take a few moments to see some examples of how people from a different century left glimpses of themselves that are still visible today!

Extra note for word lovers: The Oxford Dictionaries blog stated that “selfie” was added to the OxfordDictionaries.com (online version) in August 2013, but as of November 2013 was under consideration for (but not yet in) the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).