By Elise Dunham, Reader Services

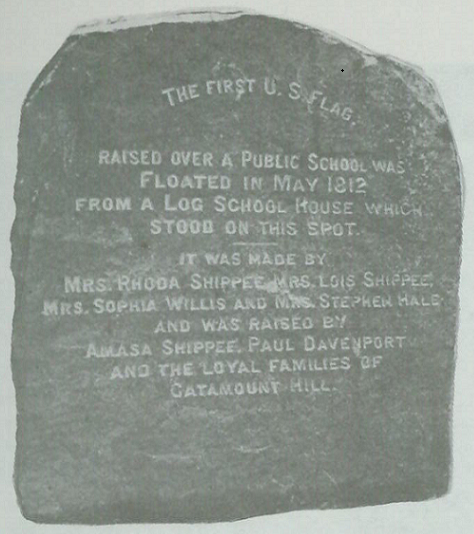

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is home to countless United States “firsts.” Among the most famous Massachusetts initiatives are claims to the first Thanksgiving celebration, the first public park, the first university, and the first public library. The Commonwealth took the lead in these and many other well-known realms, but one quiet act of patriotism that tends not to make the lists is this: In May of 1812 on the top of Catamount Hill, the Loyalists of Colrain, Massachusetts raised the first United States flag to fly over a public schoolhouse.

I had not heard of this Massachusetts first until an MHS researcher brought it to my attention earlier this summer. She was interested in learning more about the 1812 flag-raising to inform her planning of an Independence Day event at Pioneer Village at Friends of the Beaver State Park in East Liverpool, Ohio. Eager to provide the researcher with any information about this event the MHS collections might hold, I immediately took to our online catalog, ABIGAIL, and started down the path toward uncovering the story of the flag-raising on Catamount Hill.

Not hopeful that a search for “First flag-raising” would get me very far–specificity is important for conceptualizing a search, but broadening out is crucial to its success–I began with a “Subject” search for “Colrain (Mass.)”. The search led me to a number of resources that document the history of Colrain. I traversed the MHS stacks to retrieve the materials and parked myself in Ellis Hall for a good dose of reading room research. What ultimately stood out as the most compelling and useful source was A. F. Davenport’s A Sketch of the Origin and Growth of the Catamount Hill Association of Colrain, Mass ( North Adams, Mass.: Walden & Crawley, 1901). The purpose of this publication was to record the proceedings and goings-on of the Association’s various reunion events. Their Sixth Reunion, which took place in 1900, featured discussion and commemoration of the 1812 flag-raising. The momentous event was well-documented in this part of the text, and Mrs. Fanny B. Shippee’s recounting provides perspective on the political context that surrounded it:

Here, on the Hill, the Republicans largely outnumbered the Federalists, but the latter were very loud in maintaining their political views, and made up in noise what they lacked in numbers. At this, the Republicans were naturally incensed, and to show their loyalty to our government, concluded to make and erect an American flag….Those sturdy farmers were showing to the world and to the ‘Feds’ in particular that they were true to this republic.

I was certain that the researcher in Ohio would be happy to learn about the circumstances fueling the flag-raising, but I was personally eager to learn more about the story behind this event’s receipt of the “first flag-raising” accolade. I read on, and found that the MHS itself had a part to play in the construction of this snippet of collective memory:

In a reply to a communication sent to the Massachusetts Historical Society at Boston, for information in regard to the Catamount Hill flag being the first ever raised over a school-house, an answer was received saying that there was no record of any earlier flag, thus giving the Catamount Hill patriots of 1812 the credit of being the first to raise a flag over a school-house in this country.

I wish I could say that a gust of wind blew through the reading room when I read this tale of my late-19th-century counterpart’s response to a reference query about the Catamount Hill flag-raising, so similar to the one I was working on in 2013. The experience did not reach that level of melodrama, but it did bring with it an all-important reminder: “facts” are constructed, interpreted, and re-established over time, and our engagement with them will be best-informed when we manage to bear that in mind.

If you’re inspired to track down the source of another Massachusetts first, Reader Services will gladly welcome you to the library at the MHS!

***Image from A History of Colrain Massachusetts, (Lois McClellan Patrie, 1974): 9.

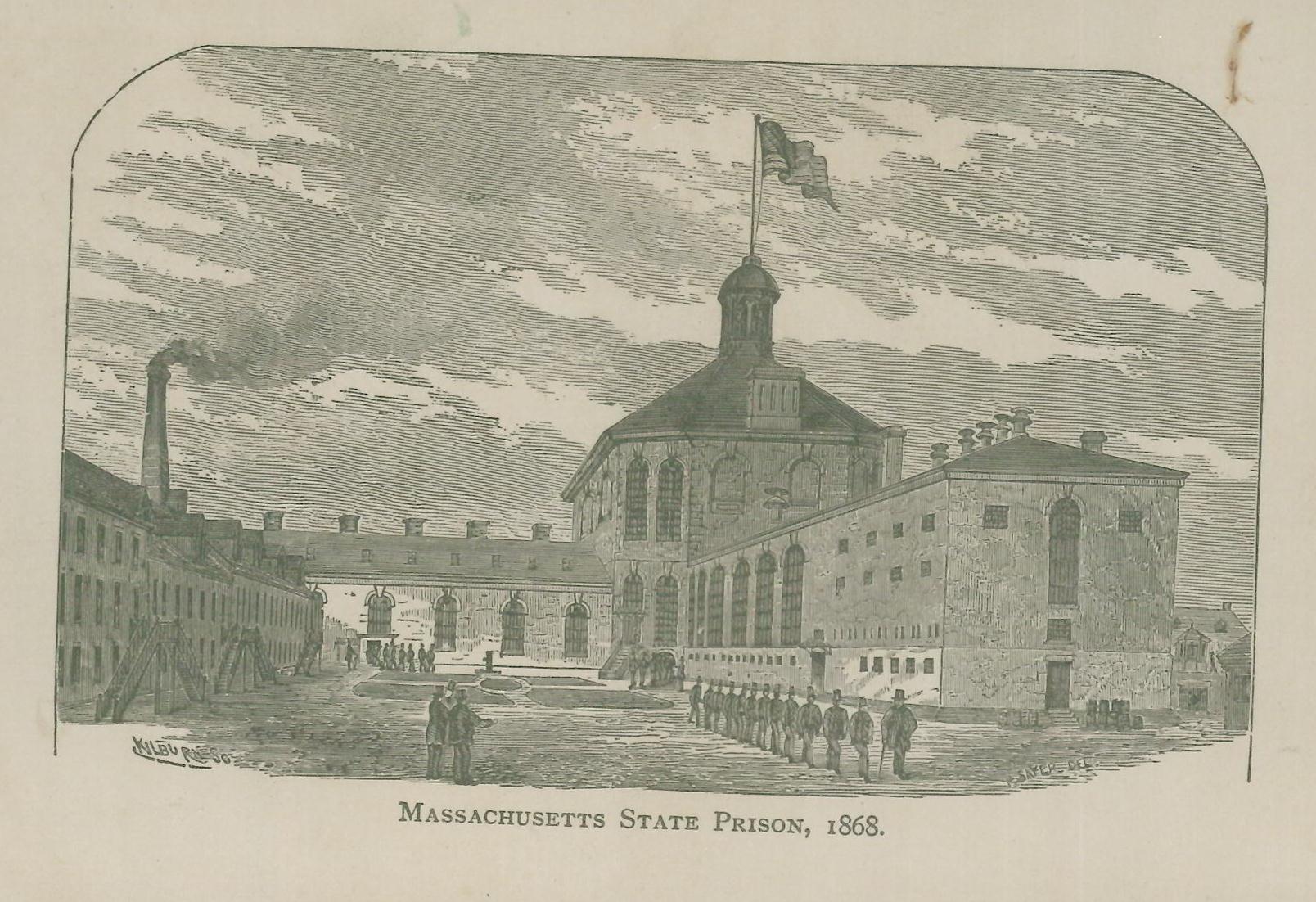

This illustration from prison warden Gideon Haynes’

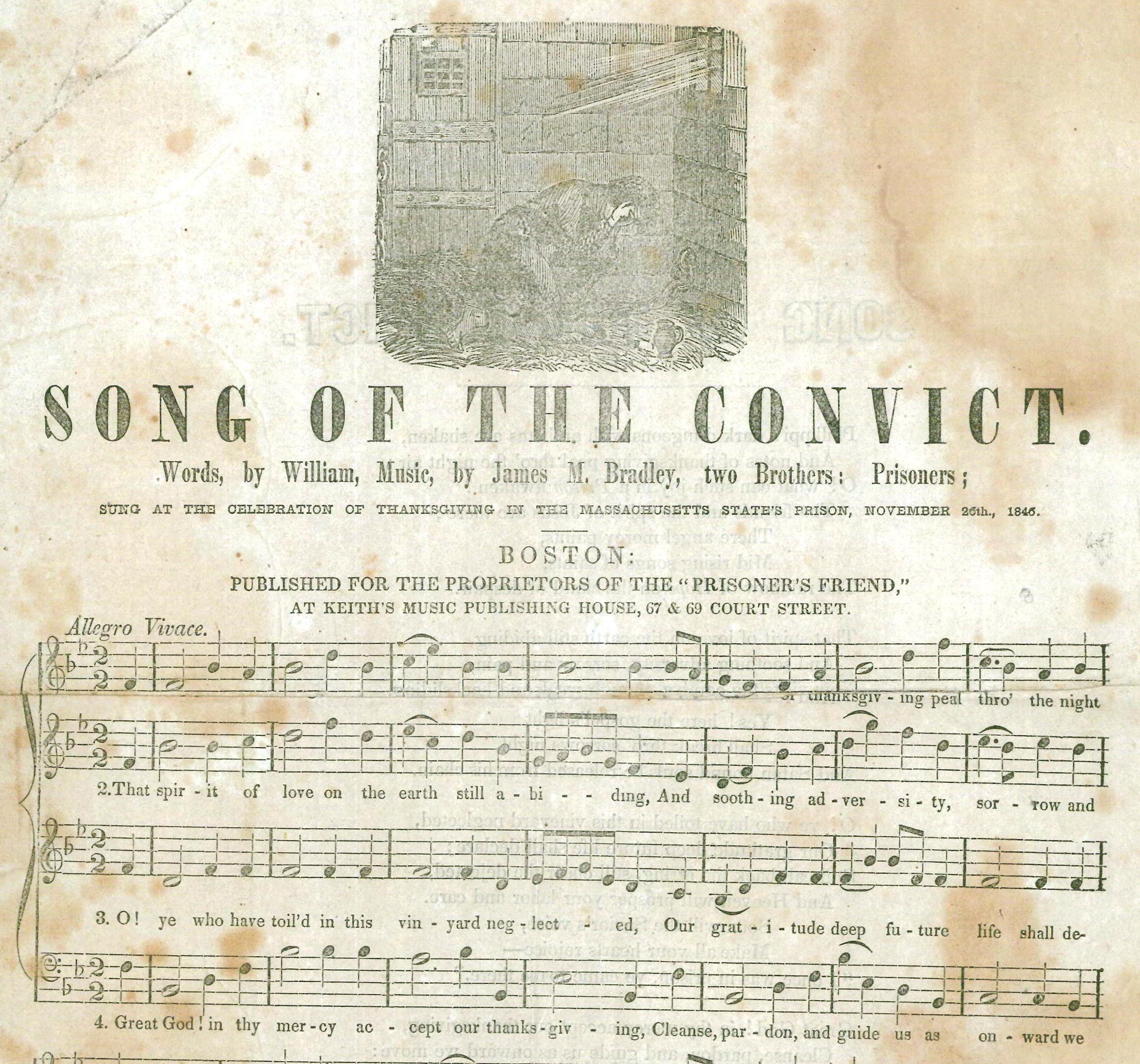

This illustration from prison warden Gideon Haynes’  A different perspective can be found in the lyrics and illustration of “Song of the Convict,”

A different perspective can be found in the lyrics and illustration of “Song of the Convict,”