Gallery

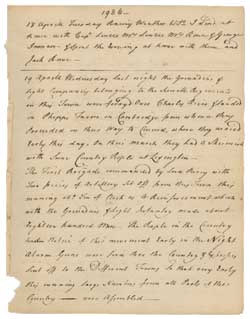

Massachusetts Provincial Congress

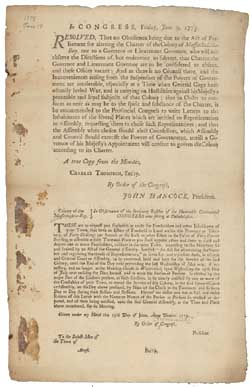

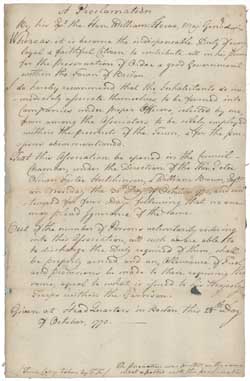

In Congress, Friday, June 9, 1775. Resolved, That no Obedience being due to the Act of Parliament for altering the Charter of the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay ...Issued by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress on 9 June 1775, this broadside outlined the regulations passed on by the Continental Congress for establishing a civil government to take control of the colony. This followed former royal governor Thomas Gage's refusal to convene the Massachusetts legislature in 1774.

Broadside

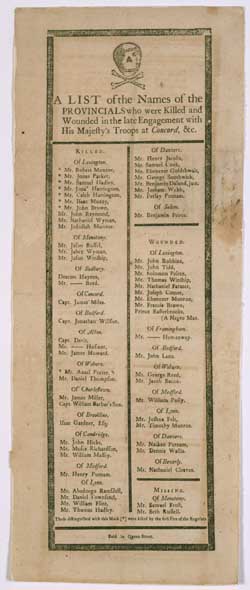

This Boston broadside lists the names of provincial men killed, wounded, or missing after the battles of Lexington and Concord. Asterisks indicate those ""killed by the first Fire of the Regulars."" Named among the wounded is the Lexington slave Prince Estabrook, the first black soldier of the Revolution.

Object

A small cannon ball, said to have been found on the side of the road near Lexington, Mass. after the Battles of Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775. It is made of lead and was the type of projectile fired from a smooth-bored cannon.

Paul Revere

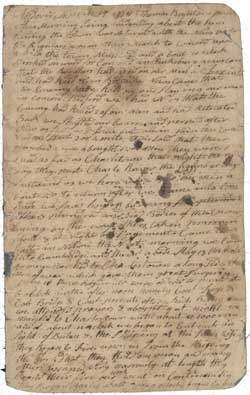

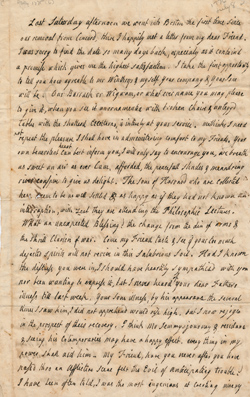

Paul Revere's deposition, fair copy, circa 1775Manuscript

In Exhibit✨

This deposition prepared by Paul Revere at the request of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, contains an account of his ride to Lexington. To prove that the British had fired the first shot at Lexington Green, the Congress solicited depositions like this from eyewitnesses in 1775.

Document

In Exhibit✨

In order to sway public and official opinion, the Provincial Congress rushed to print nearly 100 copies of these collected depositions, prefaced by a letter from Joseph Warren. Congress hoped to make an impression in London before the arrival of General Gage's own report to Parliament on the clash at Lexington and Concord. Page 3 on display

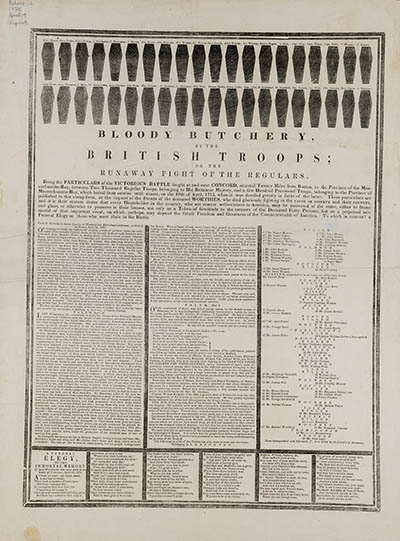

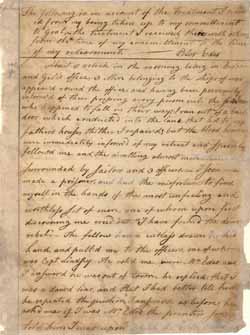

Reprint of Broadside by Ezekiel Russell

A Bloody Butchery, by the British Troops; or the Runaway Fight of the RegularsBroadside

In Exhibit✨

This publication, a reprint of the broadside published in 1775 by Ezekiel Russell in Salem, Mass., presents excerpts from the Salem Gazette, or Newbury and Marblehead Advertiser, a newspaper published by Russell. It presents accounts of the battles that occurred on 19 April as well as lists and elegies of deceased American soldiers.

Thomas Gage

A Circumstantial Account of an Attack that happened on the 19th of April 1775, on his Majesty's Troops ...Broadside

In Exhibit✨

This account of the battles of Lexington and Concord was written by General Thomas Gage from several different testimonies. Its purpose was to counteract those accounts that were biased toward the stance of the revolutionaries, many of which claimed that British troops fired the first shot at Lexington.

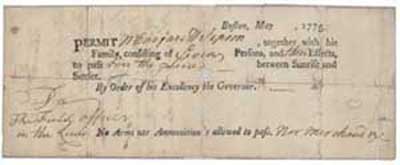

Joseph Warren

In Congress, at Watertown, April 30, 1775 : Gentlemen, the barbarous murders on our innocent brethren on Wednesday the 19th...Broadside

In Exhibit✨

In this broadside, Joseph Warren, president pro tempore of the Provincial Congress meeting at Watertown, urges his colleagues to act quickly in response to the battles of Lexington and Concord. He emphasizes the importance of raising an army and encouraging enlistment in preparation for the battles ahead.

John Hancock

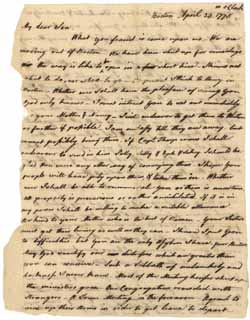

Letter from John Hancock to Artemas Ward, 22 June 1775Artemas Ward, a General from Massachusetts, has been in charge of the colonial forces camped in Cambridge since the day after the battles of Lexington and Concord. He has written to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia of the trials in organizing an army, asking for assistance or ""I shall be left all alone."" He waits for a response. A debate breaks out in Congress: should they authorize the creation of an Army of the United Colonies? If so, whom should they pick to lead it? Artemas Ward already has experience and knows his troops, but he is relatively unknown outside New England. Some members in Congress also believe it is important to raise support outside of the turbulent New England area. Attention turns to a Virginian, one who has turned up to Congress repeatedly in his military uniform.

Paul Revere

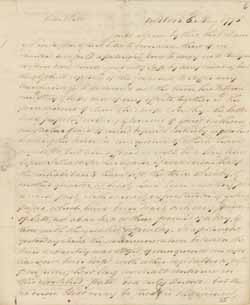

Letter from Paul Revere to Jeremy Belknap: Accounts of his famous rideManuscript

In this undated letter, written at the request of Jeremy Belknap, corresponding secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Paul Revere summarizes his activities on 18-19 April 1775: he recounts how Dr. Joseph Warren urged him to ride to Lexington (to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams of British troop movements); how he had previously arranged with some fellow Patriots to signal the direction of those movements by placing signal lanterns in the steeple of Old North Church; and how he left Boston from the ""North part of the Town,"" was rowed across the Charles River by two friends, and there borrowed a horse and began his ride. The manuscript letter includes some interlineations, apparently in the hand of Jeremy Belknap. In printing the account in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1st series, vol. 5 (1798), Belknap assigned to it the date of 1 January 1798. At the end of the document, Revere signed his name but then, apparently choosing to remain anonymous, wrote above it ""A Son of Liberty of the year 1775"" and beside it ""do not print my name."" Either he changed his mind or Belknap ignored his request, for the two phrases are crossed out in the original document, and the name is included in the printed version. The manuscript letter includes some interlineations, apparently in the hand of Jeremy Belknap. In printing the account in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1st series, vol. 5 (1798), Belknap assigned to it the date of 1 January 1798. At the end of the document, Revere signed his name but then, apparently choosing to remain anonymous, wrote above it ""A Son of Liberty of the year 1775"" and beside it ""do not print my name."" Either he changed his mind or Belknap ignored his request, for the two phrases are crossed out in the original document, and the name is included in the printed version. Revere fills most pages of his letter to Belknap (pages 2-6) with the description of his ride. He writes of avoiding British soldiers and reaching Lexington, where he conveyed information to Hancock and Adams and where he met up with William Dawes. After Revere and Dawes set off for Concord, they were joined by Samuel Prescott, who helped them ""allarm all the Inhabitents."" Revere's ride ended when he was captured by British soldiers, interrogated, and eventually released in Lexington in time to hear the opening shots of the Revolutionary War. It is interesting to compare this letter to the deposition Paul Revere wrote probably in response to a request from the Massachusetts Provincial Congress (see Paul Revere's deposition, fair copy, circa 1775; and Paul Revere's deposition, draft, circa 1775). Though fuller in some details and less detailed in others, the substance of the letter does not differ materially from Revere's account of his ride to Lexington in the earlier deposition.

Object

A powder horn, reportedly used by Nathaniel Munroe (1742-1814), at the Battle of Lexington, 1775. This powder horn is made of either a cow or ox horn; it is smoothly carved except for a long panel of black scrimshaw decoration. The decoration is a stylized vine that begins at the plug end, and it encloses the legend: ""Shrewsbury March 4th A D 1774 [corrected to 5]--Nathaniel Munrow his horn."" There is a very slight lip at the plug end, pierced twice for a missing suspension cord. The pouring spout has double ring bands, but lacks a stopper.

Thomas Boynton

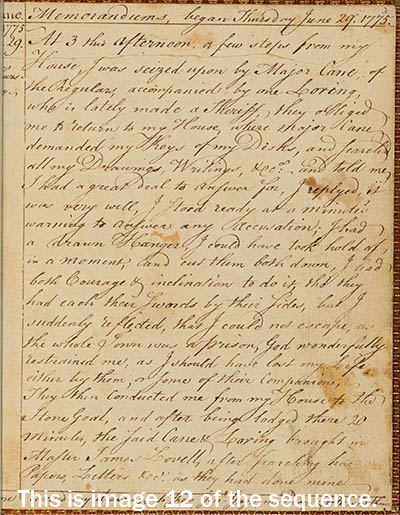

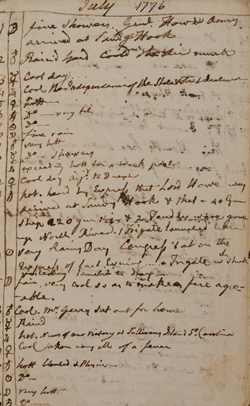

Thomas Boynton journal, 19 April- 26 August 1775Manuscript

In Exhibit✨

A fragment of the journal of Andover minuteman Thomas Boynton, kept in Andover and Charlestown, Mass., 19 April - 26 August 1775. Boynton served under Captain Benjamin Ames in Colonel James Frye’s regiment of the Massachusetts Militia. The four brief entries describe the regiment’s response to the Lexington alarm and their participation in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Peter Brown

Letter from Peter Brown to Sarah Brown, 25 June 1775This letter was written by Private Peter Brown in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to his mother, Sarah Brown, in Newport, Rhode Island. Private Brown, who came from Westford, Massachusetts, served under Colonel William Prescott in the redoubt at the Battle of Bunker Hill and describes himself as ""hearty in the cause"". His letter describes in detail the feelings and observations of a participant in the ranks, including his actions when the British marched to Concord on 19 April and his enlistment in the army at Cambridge. He describes the attack on the redoubt as the British troops are ferried over to Charlestown and shares his dawning realization of the danger the Americans are in as they build the fort and breastworks, with ""all Boston fortified against us.""

Sarah Winslow Deming

Sarah Winslow Deming journal, 1775Within this 12-page letter written in the form of journal entries from 15-26 April 1775 Sarah Winslow Deming transmits news of Lexington and Concord and the first few days of the Siege including the unpleasant conditions in the town until her difficult departure from Boston on 20 April 1775. Deming, the wife of Captain John Deming, describes various locations in Boston: Charlestown Ferry, Bartons Point, Boston Common, Boston Neck, as well as outside of the town in Jamaica Plain, Roxbury Hill, Dedham, Attleborough, and Providence.

Object

This short sabre was used by Colonel John Brooks (1752-1825) during the Revolutionary War. John Brooks was born in Medford, Mass. in 1752, the son of Caleb and Ruth (Albree) Brooks. He received medical training from Dr. Simon Tufts and began his own medical practice in 1774, the same year that he married Lucy Smith. He served as an officer in the Battles of Lexington and Concord and served under George Washington in the New York and New Jersey campaign of 1776. After the war he returned to medical practice, but continued to be active in the state militia, helping to put down Shays' Rebellion in 1787 and serving in the militia during the War of 1812. Brooks was elected governor of Massachusetts in 1816 and subsequently was re-elected every year until 1823 when he retired from public service. He died at his home in Medford in 1825.

Object

This short sabre was used by Colonel John Brooks (1752-1825) during the Revolutionary War. John Brooks was born in Medford, Mass. in 1752, the son of Caleb and Ruth (Albree) Brooks. He received medical training from Dr. Simon Tufts and began his own medical practice in 1774, the same year that he married Lucy Smith. He served as an officer in the Battles of Lexington and Concord and served under George Washington in the New York and New Jersey campaign of 1776. After the war he returned to medical practice, but continued to be active in the state militia, helping to put down Shays' Rebellion in 1787 and serving in the militia during the War of 1812. Brooks was elected governor of Massachusetts in 1816 and subsequently was re-elected every year until 1823 when he retired from public service. He died at his home in Medford in 1825.

Benjamin Goodridge

Powder hornObject

This powder horn likely belonged to either Benjamin Goodridge (1721-1805) or his son Benjamin (1746-1805), of Boxford, Massachusetts, both of whom fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Object

This British drum was captured at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775 and repainted with the patriot motto ""Independence be your boast, ever mindful what it cost"". It was later used by the 33rd Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War.

Art

Lodge and MIllar's engraving of the ""View of The Attack on Bunker's Hill, with the Burning of Charles Town, June 17, 1775"" was undertaken for Edward Barnard’s new complete and authentic History of England (1781-1783). Depicted are cannonballs flying from Boston towards Charlestown which is engulfed in flames and has many ships and boats in the water.

Map

This map of Boston and Charlestown was made in November 1775 by a British officer (possibly S. Biggs) and shows major geographic landmarks and man-made fortifications in the Boston area. Many of the entrenchments, redoubts, and fortified structures are labeled with reference numbers: ""1) Charlestown & entrenchments on the heights. 2) The Rebels Redoubt & Entrencht [of] 17th June sine demolished. 3)The difft Lines & Works of the Rebels. 4. Our works."" Also included on the map are two lists showing distances in yards between Boston and various points, as well as from Mount Pisgah, near Winter Hill in Somerville, to various points.

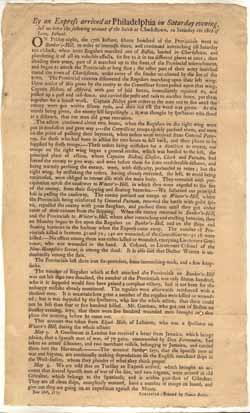

Broadside

By An Express Arrived at Philadelphia on Saturday Evening, Last We Have the Following Account of the Battle at Charlestown, on Saturday the 18th of June Instant.... Broadside printed at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, by Francis Bailey, June 26, 1775. Broadsides—single sheets printed on one side—served as public announcements or advertisements. Generally posted or read aloud, they were the popular ""broadcasts"" of the day, bringing news of current events to the public quickly. In this instance, so quickly that the Battle of Bunker Hill is misdated as taking place on the ""18th of June."" Broadsides tell us what people at a distance knew at the time and how quickly news traveled. This account was printed in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, more than 300 miles from Boston, a little more than a week after the battle.

Broadside

This broadside, written shortly after the Battle of Bunker Hill, describes the destruction of Charlestown, Massachusetts, and summarizes the military conflict and the resulting casualties. It also includes a sorrowful poem comprised of a verse of 180 lines about the signficant losses due to the battle. The lower right corner of the broadside includes an acrostic on Joseph Warren.

Object

In Exhibit✨

General Joseph Warren (1741-1775), president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and the man who enlisted Paul Revere and William Dawes to ride from Boston to Lexington on their ""midnight ride,"" died at Breed's Hill in June 1775. This sword is believed to have belonged to him.

Map

British POV

This map shows British fortifications on the Boston peninsula and the positions of both British and colonial troops on 17 June 1775. The map was published in London in the fall of 1775, and also includes a printed version of a letter from General John Burgoyne to his nephew Lord Stanley. Writing from Boston on 25 June 1775, Burgoyne described the Battle of Bunker Hill this way, ""And now ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived.""

Object

In Exhibit✨

This plaque displays swords owned by Colonel William Prescott (1726-1795) of the Massachusetts revolutionary army and Royal Navy Captain John Linzee (1743-1798), who fought on opposite sides during the Battle of Bunker Hill, the first major military engagement of the American Revolution. The swords descended through their respective families, until both ended up in the possession of historian William Hickling Prescott, who married a Linzee relation. They were mounted in 1859 for the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Art

This engraving by Bernard Romans depicts a panoramic view of the battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June 1775. Here Romans shows two ships, the city in flames and lines of soldiers facing each other. The text under the title reads:

Map

This map by Thomas Jefferys and William Faden details the position of British and American troops during the Battle of Bunker Hill in Charlestown on 17 June 1775. It provides the locations of many regiments and ships, cannons, intrenchments, and redoubts.

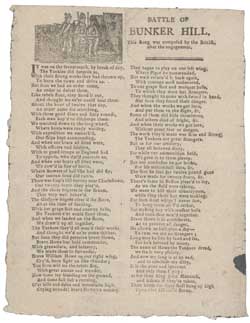

British POV

This printed document contains the lyrics of a ballad published in England after the Battle of Bunker Hill. The ballad describes the movements of British troops to Long Wharf where they got into boats, rowed across the harbor to Charlestown where, after landing on the shore, they directly fought their enemy on the battlefield.

James Warren

Letter from James Warren to Mercy Otis Warren, 18 June 1775Letter

Letter, June 18, 1775, from James Warren in Watertown, Massachusetts, to his wife Mercy Otis Warren. James Warren of Plymouth, a member of the Massachusetts General Court, married Mercy Otis of Barnstable in 1754. James, his wife Mercy, and her brother James Otis all were outspoken opponents of British rule. Mercy wrote a number of propagandistic plays and poetry in the Patriot cause; after the war, she published an early history of the Revolution. In his letter, James Warren recounts the ""extraordinary nature of the events"" leading up to and following the Battle of Bunker Hill. He also compares the death of Joseph Warren to the fate that General James Wolfe suffered during the Siege of Quebec in 1759—a comparison later captured in John Trumbull's painting The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill. James Warren succeeded Joseph Warren as president of the Massachusetts Provisional Congress.

Abigail Adams

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 18-20 June 1775Letter

Abigail Adams started writing this letter to her husband on 18 June 1775—the day after the Battle of Bunker Hill, and finished it two days later. Abigail writes from Braintree, Massachusetts, to John Adams who was in Philadelphia representing Massachusetts at the Continental Congress.

Joseph Palmer

Letter from Joseph Palmer to John Adams, 19 June 1775Letter

Letter, June 19, 1775, from Joseph Palmer in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to John Adams, who was in Philadelphia representing Massachusetts at the Continental Congress. After immigrating to America from England in 1746, Palmer operated a glassworks and various other manufacturing works in Germantown, now a part of Quincy, Massachusetts. He served in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1774 and 1775 and became a brigadier general in the Massachusetts militia in 1776. In his letter, he relates the events of the Battle of Bunker Hill in detail, including the death of their mutual friend Dr. Joseph Warren and the American army's desperate shortage of gunpowder. Compare Palmer's record to the letter Abigail Adams wrote the day before (June 18, 1775) describing the same events to her husband.

John Bromfield

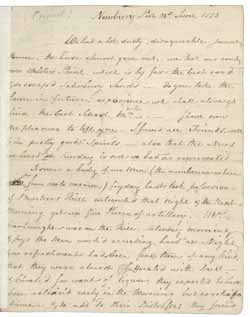

Letter from John Bromfield to Jeremiah Powell, 21 June 1775Letter

In this letter written four days after the Battle of Bunker Hill, John Bromfield of Newburyport recounts what he has heard from friends who were in Charlestown serving as part of two Newburyport companies. Bromfield's letter includes descriptions of the conditions in Charlestown; the overnight building of fortifications, the lack of food and water for the men the morning of the battle, and also the first skirmishes between the British and the colonists. Bromfield describes the casualties endured by both sides and the letter ends with the news that Joseph Warren has been killed in battle.

J. Waller

Letter from J. Waller to unidentified recipient, 21 June 1775Letter

This letter is written by Lieutenant Waller, the Adjutant of the 1st Battalion of Marines (later called the Royal Marines). The Marines, under the command of Major Pitcairn, were part of the expeditionary force that marched to Lexington and Concord, and experienced casualties, on 19 April 1775. This letter, written on 21 June 1775 includes a detailed account of the Battle of Bunker Hill, an action ""very fatal to the 1st Battalion."" Although his recipient is unidentified, it probably was a friend or fellow officer who would have been familiar with the officers of the battalion.

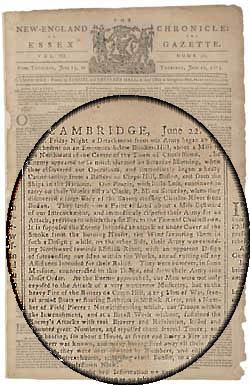

Newspaper

This newspaper article recounts significant events during the Battle of Bunker Hill, the cannonading of the American position in Charlestown from British guns on Copp's Hill in Boston's North End and the military actions that follow. The article contains a letter from a resident of Hingham, a town south of Boston, who was in Boston the day after the battle. It also contains a report from an unidentified source in Chelsea, just north of Charlestown, and an erroneous claim that either General Howe or General Burgoyne has been killed in action.

One week after the Battle of Bunker Hill, this document is printed and circulated by John Howe, a loyalist Boston printer, to demonstrate ""The Bravery of the King's Troops"" and produce a version of events that counteracts that being spread by the patriot press and Committees of Correspondence.

William Prescott

Letter from William Prescott to John Adams, 25 August 1775Letter

This letter is written by Colonel William Prescott, from the camp at the headquarters of the Continental Army in Cambridge, to John Adams who was in Philadelphia representing Massachusetts at the sessions of the Second Continental Congress. Prescott, a native of Groton, Massachusetts, and veteran of the French and Indian Wars, gives Adams a brief ""state of the facts"" of the ""Action at Charlestown""—the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June 1775. Prescott commanded the Patriot forces that fortified the heights in Charlestown and in the letter he describes the different orders sending troops to different parts of the battlefield.

John Allen

Teaspoons belonging to Relief ElleryObject

Miss Relief Ellery (later Vincent), a 20-year-old Charlestown resident, grabbed these dainty silver spoons from the breakfast table on the morning of 17 June 1775, fleeing to the woods as the British began firing on her town. When she returned, her entire home was gone. The spoons were all she had left.

Edward Savage

Joseph WarrenArt

This portrait depicts Joseph Warren (1741-1775) and was painted by Edward Savage (1761-1817), after a portrait by John Singleton Copley.

Object

A British Infantry officer’s sword believed to have belonged to First Lt. Zibeon Hooker (1752-1840), an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati. Zibeon Hooker was born in Medfield, Mass. in 1752, the son of William and Mary Hooker. In 1779 he married Sarah Barber. He began his military career at 17, as a musician in the Sherborne Company of Minute Men. He arrived at the Battle of Bunker Hill as a drummer, but when his drum was destroyed by a musket ball, he took up arms and joined the fight. The next year he fought in the British evacuation of Boston. In 1777 he enlisted with the Fifth Massachusetts Regiment, with whom he fought at Ticonderoga and Valley Forge. He continued his service under Washington until the Continental Army was disbanded in 1789, at which point he moved with his family to Newton, Mass., where he died in 1840.

This handbill, probably the only surviving copy, is an early example of American Revolutionary War propaganda, printed to encourage British soldiers to desert. It includes a satirical comparison of living conditions for soldiers on both sides of the lines as well as an appeal to British troops from an ""old soldier"" to refuse their orders to kill colonists, the ""sons of Englishmen.""

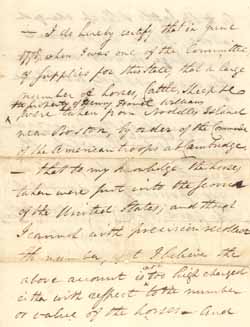

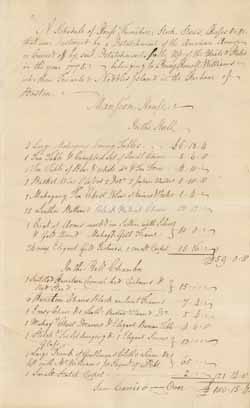

Manuscript

This statement of Moses Gill (1734-1800) certifies that the horses, cattle, and sheep removed from Henry Howell Williams's property on Noddles Island in June 1775 were used for the benefit of American troops. This manuscript is from the Noddles Island papers a collection of documents assembled by Henry Howell Williams when he requested compensation for losses incurred to his property during the Siege of Boston.

Art

These four panels, the first of which is shown, provide a panoramic view from Beacon Hill, Boston, as seen by a British officer during the siege of 1775. Each panel includes a numeric key to the major military and civilian locations shown in the illustrations. The drawing, by Lieutenant Richard Williams and Lieutenant William Wood of the Twenty-third Regiment of Foot (the Royal Welsh Fusiliers), was probably made in the late summer or early fall of 1775.

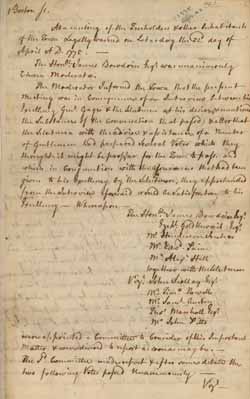

Manuscript

These manuscript town meeting minutes record the two votes passed at the meeting of property owners and residents of Boston on 22 April 1775, three days after the Battle of Lexington and Concord. The first vote pertained to peaceable actions and intentions of the Provincial army outside the city in conjunction with those men remaining in the city. In exchange for peace, inhabitants and their property within Boston would be protected by General Gage and His Majesty's Troops. The second vote related to communications and the transfer of supplies, provisions and people, which all had been prohibited once the army had blocked access at Boston Neck. Inhabitants of Boston were permitted to leave the town provided they left their arms behind at a secure location under the care of the Selectmen.

Letter

In Exhibit✨

In a letter written on 23 April 1775 (and finished on the 24th), Boston minister Andrew Eliot describes Boston shortly after the Siege began. Eliot was minister of the New North Church in Boston, and although he made great efforts to get his family safely out of Boston, he stayed to serve the members of the community and his congregation who remained in town. This letter written to one of his sons (most likely his oldest son, Andrew, who was a minister in Connecticut) describes the importance of getting his wife (Andrew Sr.'s wife) out of Boston.

Letter

In a letter written on 25 April 1775 to Thomas B. Hollis, Boston minister Andrew Eliot describes Boston shortly after the Siege began. Eliot was minister of the New North Church in Boston, and although he made great efforts to get his family safely out of town, he stayed to serve the members of the community and his congregation who remained in town. The letter discusses passionately the flight of many residents of Boston, lack of communication with the country, and being ""wholly deprived of the necessaries of Life,"" among other topics. On the fourth page is a draft letter Eliot wrote to an unknown recipient on 31 May 1775. He describes shops and warehouses being shut up, grass growing in the public walks and streets, and ""every one in anxiety and distress."" In addition to describing Boston he mentions Cambridge College (Harvard), Roxbury, and Dorchester.

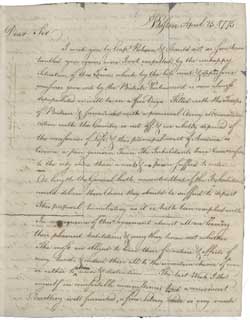

Broadside

This broadside announces the official agreement, made between General Gage and the Provincial Congress, allowing civilians to enter and exit Boston without harm while the town is occupied by British soldiers. Following the battles of Lexington and Concord, 12-13 thousand people fled Boston as a result of this agreement.

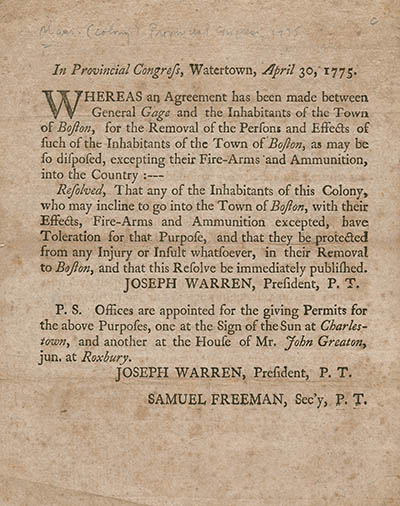

Issued by Thomas Gage

Permit to pass through British lines, May 1775In Exhibit✨

This permit, issued by General Thomas Gage, allows citizens of Boston to pass safely through British lines following the battle of Lexington and Concord. 12-13 thousand people flee Boston as a result of this agreement.

Rear Admiral Samuel Graves

Pass issued on behalf of Rear Admiral Samuel Graves to Henry Howell Williams allowing access to Noddles Island, 1 May 1775In Exhibit✨

This pass forms part of a selection of documents from the Noddles Island papers, a collection of documents Henry Howell Williams assembled when he requested compensation for losses incurred to his property during the Siege of Boston. Samuel Graves (1713-1787) was rear admiral of the Royal Navy and was stationed in Boston in early 1775. This pass authorized Henry Howell Williams unlimited access both to Boston and his residence on Noddles Island after the start of the Siege of Boston under the condition he ""carry no people from hence, or bring any thing off the Island.""

Rachel Revere

Letter from Rachel Revere to Paul Revere, 2 May 1775Letter

On 2 May 1775, Rachel (Walker) Revere wrote to her husband Paul about the difficulties she faced in leaving Boston, then under siege by American revolutionary forces after the Battles of Concord and Lexington. The outbreak of the fighting had stranded her behind British lines with six stepchildren and a new baby.

Manuscript

In Exhibit✨

This list inventories items that were destroyed or taken from Henry Howell Williams between 29 May and 2 June 1775 when American troops raided his property on Noddles Island. The detailed list (of furniture, clothing, housewares, food stores, livestock, grains, and tools) totals Williams's losses at £3,645. Williams and his wife, Elizabeth, declared the accuracy of the list in the presence of Boston lawyer William Tudor in 1787. This list is from the Noddles Island papers, a collection of documents assembled by Williams in 1787 when he formally petitioned the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for proper compensation for his losses during the Siege of Boston.

Letter

Women

In Exhibit✨

Letter from Hannah Winthrop (baptized 1727- 1790) to Mercy Otis Warren (1728–1814), circa May 1775, describing their harrowing journey to Andover, ""alternately walking & riding, the roads filld with frighted women & children some in carts with their tallest furniture.""

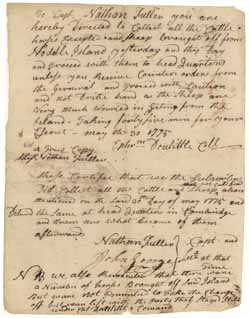

Manuscript

In Exhibit✨

In these military orders Colonel Ephraim Doolittle (spelled ""Doulittle"" in this manuscript copy) instructs Captain Nathan Fuller to seize livestock from Noddles Island on 30 May 1775. During the Siege of Boston, American troops occasionally confiscated property to use as provisions. This particular copy of Doolittle's orders was one of many documents assembled by Henry Howell Williams, the property owner who suffered losses, in the late 1780s when Williams formally petitioned the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for proper compensation.

Manuscript

In this letter written on 1 June 1775, John Andrews describes conditions in Boston. He details the struggles of various family members as they left Massachusetts in early May, his struggle to survive alone in Boston given the shortage of provisions, and general insecurity over the military activities. Andrews remained at his residence in Boston to ensure that his family's belongings were not stolen by the British troops. Andrews tells Barrell that those that leave the town ""forfeit all the effects they leave behind.""

Manuscript

This letter is written from Leverett Saltonstall (1754-1782) to Mary Cooke Saltonstall Harrod (1723-1804).

Hannah Winthrop

Letter from Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, 17 August 1775Letter

Women

Letter from Hannah Winthrop (baptized 1727- 1790), in Andover, Mass., to Mercy Otis Warren (1728–1814), 17 August 1775, describing her dismay that General Gage had forced Boston residents to leave their homes without allowing them to take any possessions. She writes of the ""Villainy"" of the British army, who promised that Boston ""should be the last place that would suffer harm"" in return for protecting the troops on their return from Concord, but instead ""[lay] a whole town in ashes.""

Based on Drawing from October 1775 by Lieutenant Richard Williams

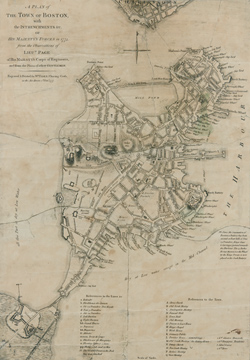

A Plan of Boston, and its Environs shewing the true Situation of His Majesty's ArmyMap

This map of the Boston area published in London in 1776 was based on a drawing made in October 1775 by Lieutenant Richard Williams, an officer in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, but not, as the map states, a trained engineer. The map includes points of military interest such as batteries and fortifications; the locations of prominent buildings (Town Hall, Faneuil Hall, and Roxbury Meeting House), roads, hills, nearby islands in Boston Harbor and the area exposed at low tide. It also notes the location of Henry Howell Williams's mansion house on Noddles Island. Oriented with north toward the upper right, this plan was drawn by and for British use and refers to the American militia as the ""Rebels.""

In Exhibit✨

Faced with a seige that must be sustained through winter, General Howe worried that his armies' hold on the city would crumble without supplies and assistance. This proclamation requests that the remaining citizens living in Boston, mostly loyalists, either enlist or offer aid to the British army.

Broadside

On Saturday 2 December 1775, during the Siege of Boston, British soldiers sought to entertain themselves with a production of The Tragedy of Zara. The play was performed at Faneuil Hall, and the proceeds were ""apply'd to the Benefit of the Widows and Children of the Soldiers."" This broadside advertisement for the play is of interest not only for the unusual circumstances under which it was performed--by the officers of the besieged British army during the opening phase of the American Revolution--but also because only the British occupation allowed a theatrical performance to take place; plays had long been banned in Puritan Boston.

John Andrews

Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 6 May 1775In this letter written to his brother-in-law on 6 May 1775, John Andrews describes conditions in Boston shortly into the Siege. Andrews mentions the large number of people to leave the town and the difficulty of communicating between town and country. As he closes the letter, Andrews says that his wife (Barrell's sister) Ruthy is preparing to leave Boston.

John Leach

John Leach diary 2, 1775-1776This is the second of two diaries kept by John Leach, a schoolmaster and civil engineer. Leach kept this diary from 29 June 1775 to 7 January 1776 and within the entries he describes his 97-day stay in a Boston prison during the Siege of Boston, prison conditions, trips to the Court of Inquiry, and the arrival and departure of prisoners. This diary also contains descriptions of the destruction of Leach’s wharf and schoolhouse by British troops in 1776.

In Exhibit✨

With the British Army in firm control of the city of Boston, Washington knows it is important to keep it bottled there, unable to attack the surrounding areas. He continues the process of fortifying the nearby strong points in Cambridge, Dorchester, and other areas. To do so, he relies on large companies of soldiers on fatigue duty: performing duties not related to fighting, such as digging trenches and building fortifications. For Washington to succeed, he needs the expertise of engineers like Captain Jeduthan Baldwin of Brookfield. Page 13 on display

![A Plan of Boston in New England with its Environs, including Milton, Dorchester, Roxbury, Brooklin [sic], Cambridge, Medford, Charlestown, Parts of Malden and Chelsea, with the Military Works Constructed in those Places in the Years 1775 and 1776 Facsimile map A Plan of Boston in New England with its Environs, including Milton, Dorchester, Roxbury, Brooklin [sic], Cambridge, Medford, Charlestown, Parts of Malden and Chelsea, with the Military Works Constructed in those Places in the Years 1775 and 1776 Facsimile map](/database/images36/5005_map_trans_work_ref.jpg)

Map

In Exhibit✨

Originally published in 1777, this 1907 facsimile printed by Boston publisher W. A. Butterfield reproduces the incredible detail captured by Loyalist Henry Pelham as he surveyed the theater of the Siege of Boston. The area covered is from modern-day Winthrop to Medford and from the area known as Squantum Point Park (in Quincy) to Brookline and shows major military works; roadways; important public buildings, farms, and wharves; rivers, creeks, and ponds and the Harbor Islands. Pelham has listed individual land owners (for example Henry Howell Williams's property on Noddles Island). In the upper left corner, this map includes an illustration of a document issued to Pelham on 28 August 1775, which granted him access to plot the geography of both British and American forces.

Map

In Exhibit✨

This manuscript map shows the shape of Boston, Boston Harbor, and the islands during the Siege. It also depicts the south shore to Hingham and includes the locations of ships, army encampments, and a lighthouse. A statement on the map conveys information about the size of the troops involved in the Siege of Boston: ""The King's Army in Boston 8000. Our army 20,000 around Boston 1776.""

Object

Maj. Samuel Selden (1723-1776) of the Connecticut Militia etched this detailed map of Boston on his powder horn during the Siege of Boston. The map shows the fortifications of the Continental Army just before the British evacuated the city. The inscription reads: ""Made for the defence of liberty.""

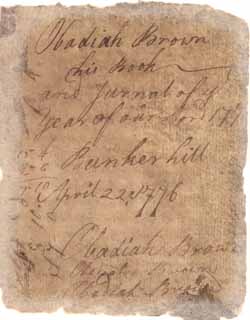

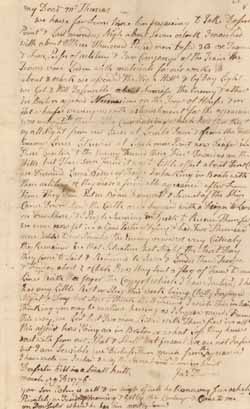

Obadiah Brown

Obadiah Brown diary, 1776-1777This diary kept by Obadiah Brown, a soldier from Gageborough (now Windsor), Massachusetts, who served as a private in a regiment near Boston during the Siege and in upstate New York in 1777, contains entries dating from 30 January 1776 to 7 January 1777. Brown's entries written during the Siege of Boston include brief descriptions of basic military duties, summaries of British troop activities, a statement about being fired upon while standing guard at Lechmere Point, and daily life--disciplinary actions and injuries--in his regiment. Brown's diary also describes his military experiences after the Siege of Boston when his regiment went to New York where he was shot in the arm.

![Poem about British by an American Lady, 11 Feb. [1776] Poem about British by an American Lady, 11 Feb. [1776]](/database/images9/5246_poem_work_ref.jpg)

Manuscript

Women

This manuscript poem by an anonymous ""American Lady"" satirically describes British officials and generals including General Thomas Gage who relinquished command of the British Army to General Howe in October 1775 and departed for England.

John Thomas

Letter from Gen. John Thomas to Hannah Thomas, 9 March 1776Letter

In this letter written to his wife Hannah from Dorchester Hill on 9 March 1776, John Thomas details the military preparations toward the end of the Siege that would lead to the evacuation of the Boston eight days later. In addition to his role as an army officer with the rank of major general, Thomas was a doctor. He died of small pox within three months of this letter.

John Sullican

Letter from John Sullivan to John Adams, 15 March 1776Letter

In this letter a commander named John Sullivan writes to John Adams, who requested that his home be checked during the fighting. Sullivan describes his division's activity, as well as the futile efforts of British troops to defend Boston after the cannons were laid in Dorchester Heights by colonial troops.

![Account of damages done to Jonathan Green during the Siege, [7 May 1776] Account of damages done to Jonathan Green during the Siege, [7 May 1776]](/database/images9/5259_account_p1_work_ref.jpg)

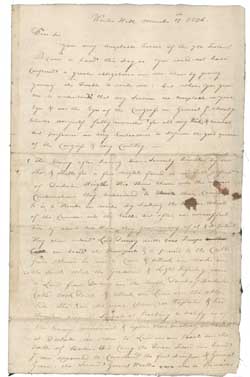

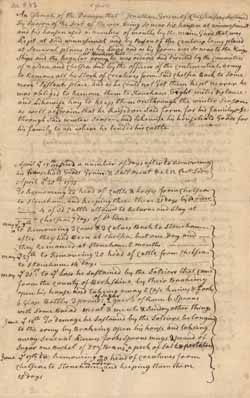

Jonathan Green

Account of damages done to Jonathan Green during the Siege, [7 May 1776]Manuscript

This two-page account lists the monetary value relating to the losses and expenses of Jonathan Green (1719-1795) of Chelsea, whose crops, property, and livestock were affected by the Siege of Boston. Green's property along Boston Harbor faced Charlestown, a location that got the attention of both the British and American troops. At the request of the Committee of Correspondence, Green moved much of his livestock inland (to Stoneham, where some of his family lived) to protect them from being taken by British soldiers. However, Green's property was damaged and his crops were lost to plundering groups of soldiers from both sides.

Jonathan Green

Estimate of damages done during the Siege, list by Jonathan Green, 7 May 1776Manuscript

This detailed list outlines the expenses and losses of Jonathan Green (1719-1795) of Chelsea, whose crops, property, and livestock were affected by the Siege of Boston. Green's property along Boston Harbor faced Charlestown, a location that got the attention of both the British and American troops. At the request of the Committee of Correspondence, Green moved much of his livestock inland (to Stoneham, where some of his family lived) to protect them from being taken by British soldiers. However, Green's property was damaged and his crops were lost to plundering groups of soldiers from both sides.

Hannah Winthrop

Letter from Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, 8 July 1776Letter

Letter from Hannah Winthrop in Cambridge, Mass. to Mercy Otis Warren, 8 July 1776, about visiting Boston for the first time since the Seige.

Object

George Washington

Congress awarded Washington this medal for his ""wise and spirited conduct in the siege and acquisition of Boston.""

Nathaniel Ober

Nathaniel Ober diary, 15 May - 3 September 1775, with accounts and notes, 1776-1781Manuscript

This diary was kept by Nathaniel Ober from 15 May - 3 September 1775. Ober, a shoemaker, served as a member of John Mansfield's Massachusetts Regiment. (This regiment was recruited in southeastern Essex County and was taken into the Continental Army when it formed in June 1775.) Although his entries describe events and army life during the Siege (including a description of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the arrival of Gen. Washington at Cambridge, the desertion of soldiers, and military punishments), on many days Ober simply writes, ""nothing remarkab[le] today.""

Peter Edes

Peter Edes diary, June-October 1775Manuscript

In this diary, Boston resident Peter Edes records entries about his capture and his 3 1/2-month-imprisonment by the British. In entries dating from 19 June 1775 to 3 October 1775, Edes, an apprentice printer (and son of the printer Benjamin Edes) writes about the difficulty of getting information about his case and describes the Boston Jail and mentions James Lovell, John Leach, and other prisoners. The last page of the diary is a list of 30 prisoners taken from the Battle of Bunker Hill and in his entry of 21 September 1775, Edes mentions that only 11 of them are still living.

William Cheever

William Cheever diary, 1775-1776Manuscript

In Exhibit✨

This brief diary kept by William Cheever in Boston from 19 May 1775 --17 March 1776 contains remarks on skirmishes between British and American troops, the food shortage, and the evacuation of the British. Diary entries make mention of many events that occurred in numerous locations: Noddles Island, Thompson Island, Charlestown, lighthouse on Little Brewster Island, Thatcher's Island, Gardner's Island, Fisher's Island, Bunker's Hill, Prospect Hill, West Hill, Roxbury, West Meeting House, Cambridge, Quebec. Cheever's diary also mentions the troubles of Henry Williams, and the imprisonment of James Lovell, John Leach, and John Gill.

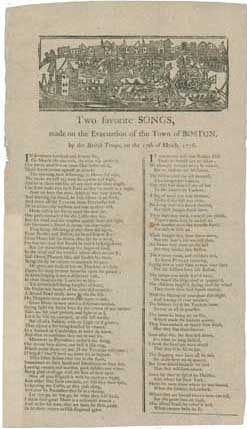

Broadside

This is one of a set of broadsides rejoicing in the retreat of the British troops from Boston. Both songs retell the events leading up to the retreat, ridiculing General Howe and celebrating the patriots' retaking of the city.

William Jackson

Letter from William Jackson to the Continental Congress, 6 July 1776Letter

William Jackson was born in Boston in 1731 and was a long-time Boston merchant. He consistently defied patriot attempts to embargo British goods during the years before the Revolution, earning him the ire of the Sons of Liberty who urged Bostonians to boycott his shop. He left Boston with the British in March 1776, but his ship was captured, and he was returned to Boston and jailed. In this letter to the Continental Congress on 6 July 1776, Loyalist William Jackson complains of his imprisonment in the Boston jail and requests that his confiscated property be recovered. Jackson also describes the evacuation of Boston on 17 March 1776. Jackson went into exile in England and was formerly banished by the Revolutionary government of Massachusetts in 1778

Isaac Bangs

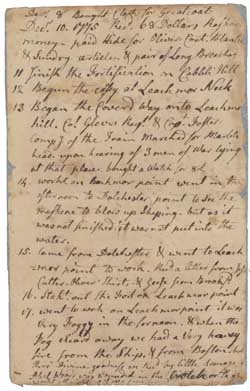

Isaac Bangs journal, 1776Manuscript

A journal kept by Isaac Bangs of Harwich, Mass. after he joined the Continental Army as a 2nd lieutenant. In journal entries dating from January - July 1776, Bangs recounts his service in a militia regiment stationed near Boston during the Siege and as an officer in New York from April - July. The entries he kept during the Siege mention the following locations: Roxbury, Dorchester, Prospect Hill, Lechmere's Point, Cobble Hill, Nooke Point and the Neck. Throughout his diary, Bangs mentions fatigue duty, the manual labor such as digging ditches or trenches that soldiers were often required to do. Bangs continues to record entries in his diary after the Siege of Boston. In late March, Bangs continued his enlistment and marched to New York. It was there on 6 July 1776 (page 89) where he heard the news of the Declaration of Independence and on 8 July 1776 (page 91) when he heard it read. Bangs reports “it was received with Joy which [the Brigades] Severally testified by three Cheers.” Bangs also discusses a major water work project in NY and attends several religious services talking at length about ""the method of the Jewish worship.""

Object

This sword belonged to General John Thomas (1724-1776) and was used by him in the French and Indian War as well as during the American Revolution.

Thomas Jefferson, John Dickinson, Continental Congress

A Declaration by the Representatives of the United Colonies of North-America, Now Met in General Congress at PhiladelphiaThis declaration was drafted by Thomas Jefferson and rewritten by John Dickinson. In it the 13 colonial representatives resolve that while a war of independence can still be avoided, colonial Americans would sooner die than continue to live in slavery. It was approved by Congress on 6 July, 1775.

John Adams

John Adams diary 25, pages 6 and 7, [memorandum of measures to be pursued in Congress]Having been voted back into his position as delegate to the Continental Congress with 126 out of 129 possible votes, John Adams keeps his diary along the road back to Philadelphia. Among the records of dinner engagements and inspections of cannon, Adams also keeps his notes on what he believes the Congress must achieve both to support the war effort, and to support the cause of independence.

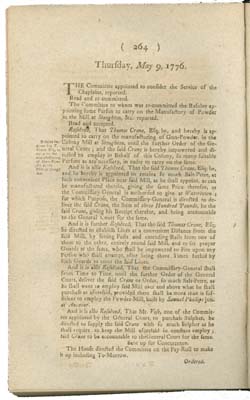

Massachusetts General Court, House of Representatives

Thursday, May 9, 1776It is May of 1776, and the delegates to the Continental Congress are still strongly divided on the question of independence. The colonial assemblies of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York have only authorized their delegates to work for reconciliation with Great Britain, which looks increasingly impossible, but the delegates from Massachusetts hope that the Massachusetts General Court will lead the other legislatures by example. Among the other business of the day, the General Court introduces a motion to prod the Massachusetts citizens into action.

In response to the Massachusetts General Court's resolution, towns all across the colony begin to draft instructions to their representatives in the Continental Congress, either for or against independence. The towns take time to deliberate and discuss, because they understand the gravity of this process. Once each town reaches consensus, local newspapers publish these instructions across Massachusetts and beyond.

All across the colonies, the movement for independence gains strength. In April, the North Carolina assembly instructs its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence if the issue is called. In May, Rhode Island makes the first public declaration of its independence from Great Britain. The towns of Massachusetts still deliberate, and while they take their time to vote, the Virginia Legislature at Williamsburg now sits to decide its position on the issue of independence. Soon the word will spread from Williamsburg to the Congress in Philadelphia and beyond.

Abigail Adams

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March - 5 April 1776Letter

Women,Philosophy of Goverment

The ""Remember the Ladies"" letter

Broadside

This broadside outlines the rules for the administration of the newly created Continental Army under Commander George Washington. Included are specific regulations for uniforms, rations, wages, munitions, and personnel, as well as designated responsibilties and allowances for officers.

"This November 1775 newspaper article from the New-England Chronicle: or, The Essex Gazette announces the printing of

Artemas Ward

Artemas Ward orderly book, 3-8 July 1775George Washington

Washington arrives in Cambridge and begins to take stock of the troops and supplies now under his command. His initial reaction is far from favorable. Later in September he records his first impressions, saying that he finds the true situation of the troops very different from what is advertised. They come from towns and villages all across the colonies, and scarcely one can agree on the same rules for functioning as another. From his very first day in charge he begins issuing new sets of general orders, which are dutifully copied down and distributed by his orderlies to his officers. Artemas Ward, now officially a Major General, keeps careful notes of all the new General's rules and requirements in his Orderly Book.

Edmund Randolph (kept minutes)

Minutes of a conference, held by the delegates of the honble Continental Congress with General Washington, 18-22 October 1775George Washington

The troops assembled in Cambridge come from multiple colonies and various backgrounds, with different levels of military training and experience, different expectations on how to relate to their superior officers, different weaponry, and even different ideas about how long they will be serving in the cause of the revolution. Even their campgrounds vary from military standard canvas tents to sod houses with doors and windows. Food and supplies from nearby towns and fields are exhausted, and over 20,000 men need to be fed, housed, clothed, and trained. From this confusion, Washington, Franklin, and others seek to create the guidelines for the new Army of the United Colonies.

Robert Harrison

Letter from Robert Harrison to Loammi Baldwin, 13 November 1775Letter

This letter, written on 13 November 1775 from the Continental Army's headquarters in Cambridge, from Robert Harrison to Col. Loammi Baldwin in Chelsea grants permission to distribute livestock such as oxen and milch cows. Harrison, an aide-de-camp of General George Washington, cautions Baldwin of the importance that the livestock not fall into the hands of the British soldiers.

Object

This cuttoe, an American Revolutionary War era sidearm known alternately as a hanger, or cutlass, belonged to Major General Artemas Ward (1727-1800). Artemas Ward was born in Shrewsbury, Mass. in 1727, the son of Nahum and Martha (How) Ward. He graduated from Harvard in 1748 and married Sarah Trowbridge of Groton in 1750. Ward was a colonel in the French and Indian Wars, a member of the provincial council, and general and commander-in-chief of the Massachusetts troops in 1775 until George Washington assumed command of the Continental Army. He was chief justice of the Worcester county court of common pleas, a member of the first and second Massachusetts provincial congress and the Continental Congress, the United States Congress and the Massachusetts legislature. He died in Shrewsbury in 1800.

Object

These pistols belonged to Artemas Ward (1727-1800), a major general in the American Revolutionary War and a Massachusetts Congressman.

Manuscript

The troops assembled in Cambridge come from multiple colonies and various backgrounds, with different levels of military training and experience, different expectations on how to relate to their superior officers, different weaponry, and even different ideas about how long they will be serving in the cause of the revolution. Even their campgrounds vary from military standard canvas tents to sod houses with doors and windows. Food and supplies from nearby towns and fields are exhausted, and over 20,000 men need to be fed, housed, clothed, and trained. From this confusion, Washington, Franklin, and others seek to create the guidelines for the new Army of the United Colonies.

Thomas Sully

Artemas WardArt

This portrait of Revolutionary War general Artemas Ward (1727-1800), commissioned by Ward's grandson Nahum Wood circa 1830-1840, is by Thomas Sully (1783-1872). Sully copied an original portrait painted by Charles Willson Peale in 1794-1795 but Sully's portrait depicts General Ward in his military uniform.

The December 1775 Prohibitory Act, which severed trade between England and its colonies and removed the colonies from the King's protection, doomed colonial trade vessels to attacks by England as well as other countries. In response, Congress released this broadside declaring that American vessels would answer aggression with aggression, arming trade ships and taking English vessels as ""lawful Prize.""

![Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy by Thomas Jefferson, 1776] Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy by Thomas Jefferson, 1776]](/database/images/declaration_1_ref.jpg)

Thomas Jefferson

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy], page 1 by Thomas JeffersonThis manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence, one of several in Jefferson's hand, represents the Declaration as drafted by the Committee of Five. This copy is comprised of 4 pages; pages 3 and 4 are fragments only. This copy is sometimes referred to as the ""Washburn Copy of the Declaration of Independence"" since it was given to the Massachusetts Historical Society by Mr. and Mrs. Arthur C. Washburn in 1893. For additional information about this and other copies of the Declaration, please see: The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text, revised edition, by Julian P. Boyd, edited by Gerard W. Gawalt. (Library of Congress and the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Inc., 1999.)

![Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy] handwritten copy by John Adams, before 28 June 1776 Manuscript Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy] handwritten copy by John Adams, before 28 June 1776 Manuscript](/database/images/1938dci1JADeclarationp1_ref.jpg)

John Adams

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy] handwritten copy by John Adams, before 28 June 1776On 11 June 1776, Congress appointed a committee of five to draft a formal declaration of independence: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. In his Autobiography, Adams wrote that he and Jefferson were members of a subcommittee, and that he pressed the chore upon his younger colleague for a variety of political and personal reasons; Jefferson simply said that he was chosen by the committee as a whole to draft the document. Scholars now generally agree that Jefferson showed his draft first to Adams and then to Franklin before he presented it to the entire committee. On 2 July 1776, once the resolution on independence passed, Congress turned immediately to the Declaration itself and the committee of the whole considered its language. At an early stage of the revisions, before it was even presented to the committee of five, Adams copied the entire document. The Adams copy is extremely important for demonstrating the evolution of the text from Jefferson's ""original Rough draught,"" as he called it, which exists now only as a much marked-up document, to the Declaration so familiar today.

Art

This portrait of Robert Treat Paine (1731-1814), delegate to the Continental Congress and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was begun by painter Edward Savage (1761-1817), who painted Paine's head and face, and finished by John Coles, Jr. (1776?-1854).

John Adams

Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776 ""Had a Declaration""Letter

The Continental Congress resolved on 2 July 1776 ""That these United Colonies are, and of right, ought to be, Free and Independent States."" The next day, 3 July 1776, John Adams wrote to Abigail Adams, and reflected on the event and tried to sum up what it meant for Americans of his own time and in the future. He was right about everything except the date:

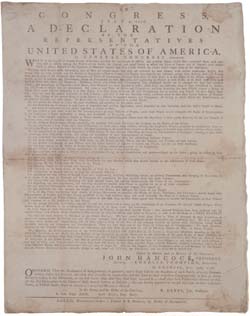

Printed by John Dunlap, Philadelphia

In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress Assembled.On 4 July 1776, the Committee that had drafted the Declaration of Independence presented their corrected and approved text to the printing shop of John Dunlap. The small number of copies that he printed that night provided, as they went forth the next day, the first step in the official declaration of independence throughout the colonies. Independence was proclaimed in Philadelphia on 8 July, in New York on 9 July (where the document was read aloud to Washington's assembled army), and in Boston on 18 July. At each new stop, local printers reprinted the text in their own newspapers and broadside editions. Despite its hurried production, this handsomely printed version of the Declaration conveyed the revolutionary news throughout the new nation and fixed 4 July as the national anniversary. (The famous manuscript copy at the National Archives was authorized and signed after the fact.) The Massachusetts Historical Society's copy is one of only 25 known copies of the first Dunlap printing, the most important single printed document in American history.

Robert Treat Paine

Robert Treat Paine diary, unnumbered page with entries for July 1776In his diary entry for 4 July 1776, Robert Treat Paine, a delegate to the Continental Congress from Massachusetts, records the weather and gives us a matter-of-fact description of the epochal events in Philadelphia: ""Cool, the Independence of the States Voted and declared."" Paine provides some contextual information about the Declaration of Independence (the weather), but frustrates our wish for a more detailed eyewitness account.

Printed by Mary Katherine Goddard, Baltimore

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of AmericaThis broadside was the first printed copy of the Declaration of Independence to list the names of the signers, except Delaware's Thomas McKean, who probably signed the Declaration later. The MHS copy of this document, printed in Baltimore by Mary Katharine Goddard, includes the signatures of John Hancock and Charles Thomson.

John Rowe

John Rowe diary 13, 18-20 July 1776, page 2197In his diary entry for 18 July 1776, John Rowe writes that the Declaration of Independence was read from the balcony of the ""Council Chamber"" in Boston (the building that is now known as the Old State House).

Henry Alline

Letter from Henry Alline to his brother and sister, 19 July 1776Letter

Yesterday the Declaration for Independency was Published out of the Balcony of the Town House. In this letter to an unnamed brother and sister, Henry Alline, Jr. describes how the Declaration of Independence was proclaimed in Boston on 18 July 1776.