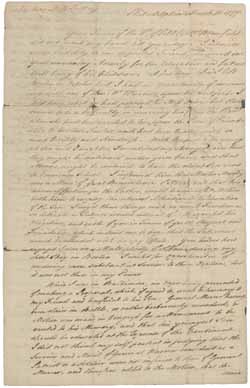

Letter from Samuel Adams to Mercy Scollay, 18 March 1777

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

The Death of Warren

At the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June 1775, although he was a leader of the Massachusetts Revolutionary government and had been commissioned as a major general two days before, Dr. Joseph Warren died fighting as an ordinary volunteer during the final British assault on the American redoubt on Breed's Hill. The battle was a moral victory for the American forces, but at great cost. Many people, including Warren's close friends John and Abigail Adams, saw his death as a heavy blow to the Revolutionary cause; please see the online presentation of Abigail Adams's letter mentioning the death of Warren.

Who was Joseph Warren?

Joseph Warren was born in Roxbury in 1741, the son of Joseph and Mary (Stevens) Warren. He graduated from Harvard in 1759 and married Elizabeth Hooton in 1764. Elizabeth died in 1773 at the age of 26, leaving Joseph the parent of four children under the age of 10 -- Elizabeth, Joseph, Mary, and Richard. In 1774, Warren met Mercy Scollay, a Boston schoolmistress; their engagement would be cut short by his death in 1775.

Warren had a successful medical practice in Boston and was one of the town's most prominent citizens. A radical leader in activities leading to the Revolution, Warren delivered addresses commemorating the Boston Massacre in 1772 and 1775, and drafted the Suffolk Resolves. He also was a member of the St. Andrews Lodge of Freemasons, a group that included many participants in the patriot movement. Elected to the Provincial Congress in 1774, Warren served as president pro tem and was chairman of the Provincial Committee of Safety.

Honoring the Revolutionary dead

From the time of his death in June 1775 until early the following year, Warren's children stayed with Mercy Scollay and the Freemasons contributed money for their care. During the Siege of Boston, a smallpox epidemic ravaged the city and the children were moved to safety at their uncle Ebenezer's home in Worcester, Mass. In 1777, the children returned to Scollay's home in Boston, as Samuel Adams and their uncle Dr. John Warren "thought it best that the three children should be kept together" (elder son Joseph was being educated at the school of Rev. Phillips Payson of Chelsea).

The question of the children's education was first raised by Mercy Scollay in a 1776 letter to John Hancock and later acted upon by Samuel Adams and Benedict Arnold. The death of Gen. Hugh Mercer, another physician turned soldier, who had been mortally wounded at the Battle of Princeton, 3 January 1777, sparked a movement in the Continental Congress to erect a monument in his honor and for the nation to pay for the education of his youngest son. In his letter to Mercy Scollay, Adams reports that "an opportunity presented of making a Proposal, which, if agreed to, would be honorary to my friend and beneficial to his Son ... I did not think my self partial in judging that the services and Merit of General Warren considered as a Patriot or as a Soldier were not inferior to those of General Mercer, and therefore added to the Motion that the same Honor should paid to his memory and that one of his Sons should be educated ..."

In 1778, Benedict Arnold learned that Congress had done nothing for the care or education of Warren's children. Arnold sent Mercy Scollay a letter accompanied by five hundred dollars and instructions for Richard to be clothed and sent to the best school in Boston. Arnold continued his advocacy for Warren's children, twice petitioning Congress for their support. His appeal was rebuffed at first but succeeded the second time--in July 1780, Congress allowed Warren's heirs the half-pay pension of a major general from the date of his death until the youngest was of age.

After his marriage in 1777, young Dr. John Warren adopted his orphaned nephews and nieces. Both of Joseph Warren's sons died at an early age: Joseph graduated from Harvard in 1786, but died suddenly in 1790 at the age of 22; Richard, a merchant in Alexandria, Virginia, died in Boston at age 21. Daughter Mary married Judge Richard E. Newcomb of Greenfield, Mass.; had one son, Joseph; and died in 1826. Elizabeth married Gen. Arnold Welles and lived in Boston, dying at the age of 39 in 1804.

Suggestions for further reading:

Cary, John H. Joseph Warren: Physician, Politician, Patriot. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Fowler, William M. Samuel Adams: Radical Puritan. New York: Longman, 1997.

The John Collins Warren Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society include the manuscripts of four generations of Warren family physicians: Joseph Warren (1741-1775), his brother, John Warren (1753-1815); John's son, John Collins Warren (1778-1856); John Collins's son, Jonathan Mason Warren (1811-1867); and Jonathan Mason's son, John Collins Warren (1842-1927).

Ketchum, Richard M. Decisive Day: the Battle for Bunker Hill. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974.

Truax, Rhoda. The Doctors Warren of Boston: First Family of Surgery. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1968.

For more about Dr. John Warren, see the November 2004 Object of the Month.