Analyzing the Meaning and Legacy of the Declaration of Independence

Inquiry Question 1: According to the Declaration of Independence, why did the colonies declare independence from Great Britain?

Inquiry Question 2: In what ways did individuals use the Declaration of Independence to argue for the end of slavery?

- Historical Context

-

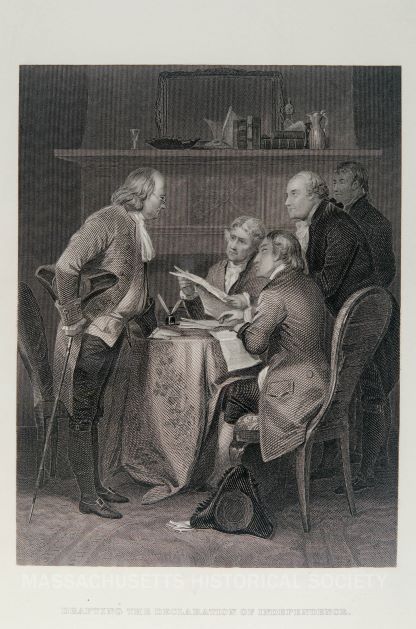

Drafting the Declaration of Independence, Engraving by Alonzo Chappel, 1857, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/3306 Student Background

The Declaration of Independence was written in the summer of 1776 at the first Continental Congress. Drafted by Thomas Jefferson and edited by four other committee members, the Declaration laid out for the King and the rest of the colonists their reasons for claiming independence from Great Britain. It was intended to inspire the colonists to fight against the Crown and to put their lives on the line for the cause. The writers detailed specific grievancescomplaints against the King for his taxation without representation, quartering of soldiershousing soldiers in colonists’ homes, waging war on the colonies, and a long list of other problems. The writers also included a list of ideals they held for a new government that understood that “all men are created equal” and the government should guarantee “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of happiness” for all individuals.

Source Set

Download Source Set

Glossary

Broadside:

a sheet of paper with information printed on one or both sides that is meant to be shared publicly

Manuscript:

a handwritten, unpublished document

Declaration:

a formal statement or announcement

Unanimous:

fully in agreement; all decision-makers agree with one another

Inalienable:

cannot be taken away or given away

Petition:

a written request to an authority (e.g., Legislature), usually signed by many people

Analyzing Primary Sources

As you read the primary sources, consider:

-

Who wrote the document?

-

When was the document written?

-

What is the document’s purpose?

-

Who was the intended audience for the document?

Created by MHS staff and Katharine Cortes, PhD, University of California, Davis

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

This manuscripta handwritten, unpublished document copy of the Declarationa formal statement or announcement of Independence, one of several written by Jefferson, represents the Declarationa formal statement or announcement as drafted by the Committee of Five. This copy is four pages long, but pages three and four are fragments (pieces) only.

Citation: Jefferson, Thomas, Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy]. 4 pages, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/thomasjeffersonpapers.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.

After the Committee of Five drafted the Declarationa formal statement or announcement of Independence, the Continental Congress made additional changes and then approved the text. On July 4, 1776, the Congress sent the text to the printing shop of John Dunlap, who printed a small number of copies that night. Messengers rode on horseback to deliver copies of the Declarationa formal statement or announcement of Independence to all of the colonies, where it was read aloud publicly. To reach more people, the text of the Declarationa formal statement or announcement of Independence was also printed in newspapers and on broadsidesa sheet of paper with information printed on one or both sides that is meant to be shared publicly.

The MHS also holds a printed copy of the Declaration of Independence from 1777 that refers to the document as “unanimousfully in agreement; all decision-makers agree with one another” in its title and includes the names of the signers (except for Delaware’s Thomas McKean, who probably signed later).

Citation: In Congress, July 4, 1776, A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress Assembled, Broadside, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/50.

Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony ‘that these united Colonies, are, and of right ought to be free and independent States, and as such, they have, and of Right ought to have full Power to make War, conclude Peace, establish Commerce, and to do all the other Acts and Things, which other States may rightfully do.’

The Continental Congress voted in favor of independence on July 2, 1776. On July 3, John Adams wrote two letters to his wife, Abigail Adams. In the final two paragraphs of this first letter, John Adams describes the importance of the Continental Congress’s unanimousfully in agreement; all decision-makers agree with one another vote in favor of independence from Great Britain. Adams also briefly reflects on the originsbeginnings of the separation between Great Britain and the colonies, and how the call for independence came to be.

Citation: Adams, John. Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, "Your Favour of June 17...". 2 pages. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L1776.

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.—I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival.

The Continental Congress voted for independence on July 2, 1776. On July 4, the Congress formally adopted the written Declarationa formal statement or announcement of Independence. In this second letter to his wife Abigail, John Adams describes what he thought the lasting impact, or legacy, of this moment would be for future generations. (Notice which date he thought would be used for annual celebrations.)

Citation: Adams, John. Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776, "Had a Declaration..." . 3 pages. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society,https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L1776.

...The petitiona written request to an authority (e.g., Legislature), usually signed by many people of A Great Number of Blacks detained in a State of Slavery in the Bowels of a free & christian Country Humbly… Apprehendunderstand that they have in common with all other men a natural and inalienablecannot be taken away or given away right to that freedom … bestowed equally on all mankind…They were unjustly dragged by the hand of cruel power… from a populous pleasant and plentiful country and in violation of laws of nature and off nations …brought here either to be sold like beast of burthen & like them condemnd to slavery for life…They cannot but express their astonishments that … every principle from which America has acted in the course of their unhappy difficulties with Great Britain [applies to] your petitioners.

In this petitiona written request to an authority (e.g., Legislature), usually signed by many people , free Black men in Massachusetts state their case for freedom, suggesting that such is the natural right of all people. This is a manuscripta handwritten, unpublished document copy of a petitiona written request to an authority (e.g., Legislature), usually signed by many people . An official copy, dated 13 January 1777, was submitted to the legislature and was signed by Prince Hall (1735-1807) and seven other free Black men.

The excerpt from the petitiona written request to an authority (e.g., Legislature), usually signed by many people quoted in the gray box has been modified for clarity.

Citation: Petition for freedom (manuscript copy) to the Massachusetts Council and the House of Representatives, [13] January 1777, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/557.

Read a longer excerpt.

What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?...

The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine…

Born into slavery in Maryland, Frederick Douglass learned how to read and write and, in 1838, freed himself. He and his wife, a free Black woman, escaped to New York and then Massachusetts. He became a noted speaker for abolition and women’s rights. In 1845, he published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass spoke to the ladies’ anti-slavery sewing society at Corinthian

Hall in Rochester, New York. His speech was then printed and published in what is now known as Douglass’ “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” speech.

Citation: Frederick Douglass, photomechanical, halftone, oval image, from Portraits of American Abolitionists (a collection of images of individuals representing a broad spectrum of viewpoints in the slavery debate), Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/1050.

To-day, we are called to celebrate the seventy-eighth anniversary of American Independence. In what spirit?... With what purpose? To what end? [The Declaration of Independence had declared] that all men are created equal ... It is not a declaration of equality of property, bodily strength or beauty, intellectual or moral development, industrial or inventive powers, but equality of RIGHTS--not of one race, but of all races.

William Lloyd Garrison speaking at anti-slavery rally in Framingham, MA, July 4, 1854

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society published this broadsidea sheet of paper with information printed on one or both sides that is meant to be shared publicly advertising a Fourth of July rally they were sponsoring in Framingham in 1854. Black and white abolitionists–including Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison, and Henry David Thoreau–addressed the crowd. In a dramatic climax, Garrison burned copies of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law and the United States Constitution.

Citation: No Slavery! Fourth of July! The Managers of the Mass. Anti-Slavery Soc'y .. Broadside, Worcester: printed by Earle & Drew, [1854], Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/database/431.

For Teachers

Complete list of excerpts, transcriptions, and worksheets

Historical Overview for students and teachers

Supplementary: Excerpts from firsthand accounts describing the public reading of the Declaration of Independence in Boston, 18 July 1776

Created by MHS staff and Katharine Cortes, PhD, University of California, Davis

Analyzing the Meaning and Legacy of the Declaration of Independence

Teacher Background Reading

- Historical Overview: Analyzing the Meaning and Legacy of the Declaration of Independence

-

In the summer of 1776, the Continental Congress selected a Committee of Five to draft a formal statement declaring independence from Great Britain. The five men on the Committee were Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert L. Livingston. Jefferson wrote the initial draft and the other committee members commented upon and edited it. The Continental Congress then made further changes before the Declaration of Independence was shared with the thirteen colonies—and the world.

Intended for not just the King, but fellow colonists and the world to read the document, the writers of the Declaration of Independence infused the document with their ideals for humanity. The writers argued that “all men are created equal” and that they held God given rights to “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of happiness.” They insisted that the colonists had the right to overthrow a tyrannical government and install a new one that would be in alignment with their vision of a representative government that would protect the rights of individuals and provide for stability of economy, security, and identity. By detailing the multitude of transgressions made by the King,they had intended the Declaration to rally the colonists to revolution and put their lives on the line.

But the Declaration was not without its own hypocrisy. In addition to ignoring the enslavement of Africans by many of the signatories, it also signals the ways the founders intended to treat Indigenous communities as an independent nation. One of the often overlooked grievances in the Declaration claims, “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” This grievance highlights a central paradox of the Revolutionary era. On the one hand, leaders of the colonies invited representatives from the Iroquois nation to the writing of the Declaration to counsel them on governing a geographically large nation. On the other hand, they utilized racist rhetoric to justify war on the frontier and take Indigenous lands. The writers of the Declaration used the racial prejudice against Indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans to help unite the disparate colonists who agreed on little else.

While the text of the Declaration is essential for students to understand as it provides the basis for many of the ideals and beliefs we hold today, what is equally important is for students to examine its legacy. Students should also explore the multitude of ways that individuals have used the Declaration to argue for their own rights. For example, in 1848 at the Seneca Falls convention, the female delegates presented their “Declaration of Sentiments” that closely mimics the text and content of the Declaration of Independence. They declared “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” calling attention to women being denied rights and using the language of the document to strengthen their argument. Others such as Benjamin Banneker and Frederick Douglass used the language of natural rights, liberty, freedom, and denunciation of tyrants to call for the end of slavery. Benjamin Banneker, a free Black man born in Maryland, exchanged letters with Thomas Jefferson in 1791 in an effort to convince the politician that Black individuals were equal to whites, but that the institution of slavery prevented equality. Together, Banneker and Douglass’s words highlighted the hypocrisy of the founders like Thomas Jefferson who claimed to be enslaved by Great Britain while owning enslaved persons themselves.

Sources

- Examining A Racist Passage In The Declaration Of Independence : NPR (Ari Shapiro, host, and Professor Donald Grinde Jr., Yamassee Nation)

- How the Iroquois Great Law of Peace Shaped U.S. Democracy | Native America (pbs.org) (Terri Hansen, Winnebago tribal member)

- Founding Fathers and Slaveholders | History| Smithsonian Magazine (Professor Stephen E. Ambrose)

Close Reading Questions

- Inquiry Questions

-

Declaration of Independence (Jefferson draft)

-

Who did Jefferson and the Continental Congress include in the phrase "all men are created equal"? Who did they exclude?

In 1774, Thomas Jefferson enslaved 187 people. On pages 15-18 of his Farm Book, Jefferson recorded on which of his seven plantations the people he enslaved lived. He lists each person's name and sometimes indicates their birth year; he draws brackets around families; and he also notes the people he has sold or hired out to another enslaver. Students can look at pages 15-18 of the Farm Book to see the names of the people who made Jefferson's wealth, and time away from his home to pursue politics, possible.

Everyone in the Continental Congress was a white man. Many were also enslavers. Students can look at a list of all of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence | National Archives to see the names and occupations of the framers.

-

How many are listed as "plantation owners"?

-

(Remember also that some, like John Hancock, were not plantation owners but did enslave small numbers of people to work in their households, or in skilled crafts.)

-

John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776 (letter 1)

John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776 (letter 2)

-

According to Adams, what rights do “free and independent States” have?

-

He tells Abigail that the Declaration of Independence will lay out the causes that led to it and the reasons that will justify it. Return to the Declaration. Do the writers identify the major causes that led to Independence?

-

Adams says “Britain has been filled with folly [foolishness] and America with wisdom”. Where in the Declaration of Independence do the writers list one of Britain’s “follies”?

-

What does the Declaration of Independence and John Adams’ private writings tell you about what the writers of the Declaration believed?

-

How important was the role of published texts to the cause for independence?

-

In his letters, Adams emphasizes that the Declaration was adopted unanimously by all colonies. The word “unanimous” is also used to begin the Declaration of Independence itself. Why was unanimity so important to the framers?

-

Why do you think it is important that we have a document written by free Black and enslaved peoples?

-

What is their view of Africa?

-

What do they want from the Massachusetts House of Representatives?

-

In what ways are they referencing the Declaration of Independence?

No Slavery! Fourth of July!, Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, 1854

-

Why are they holding this rally on July 4th? What are they trying to signal?

-

How do they feel about the institution of slavery?

-

In what ways are they using the language of the Declaration of Independence in their announcement?

The below documents are not part of the source set, but are used in the “Legacy of the Declaration: Pairs Squared” Jigsaw Activity.

-

To what rights and privileges is Banneker referring?

-

Of what act does Banneker find Jefferson guilty?

Frederick Douglass 1852 Fourth of July speech excerpt

-

What is Douglass’ opinion of the 4th of July? What does the day mean for free Black and enslaved people?

-

What principles does he feel only apply to white people and not Black people?

-

Suggested Activities

- Reading for Meaning

-

Materials:

Teacher Directions

Note: In this activity, students read some of the colonists' grievances against the King. They do not read the final grievance ("[King George III] has excited domestic insurrections amongst us. . ."), which uses racist terminology to describe Native Americans. If you choose to read this passage with your students, it is important to frame this grievance so that your students understand it is racist and was included to inflame anti-Indigenous sentiment in white people as the U.S. tried to claim more land in the (then) west.

In groups, students will work together to identify the reasons the Declaration of Independence gives for seeking independence. Students will then identify which of those reasons are the most compelling.

- Read the Declaration of Independence excerpt out loud as a class.

- As a class, discuss what some of the more difficult passages mean, identify vocabulary, and allow students a chance to take notes.

- In groups, students work together to paraphrase each passage excerpt and answer the guiding question.

- In their groups, students jig-saw the paraphrasing of some of the grievances. Students then draw arrows between the grievances and Revolutionary events.

- Contemporary Perspectives

-

Materials:

John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776 (letter 1)

John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776 (letter 2)

Contemporary Perspectives excerpts and discussion questions worksheet

In this activity, students can read both letters in their entirety, or read excerpts from the two letters John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail on July 3, 1776.

Context:

The Continental Congress voted for independence on July 2, 1776. On July 4, the Congress formally adopted the written Declaration of Independence.

In the final two paragraphs of the first letter, John Adams describes the importance of the Continental Congress’s unanimous vote in favor of independence from Great Britain. Adams also briefly reflects on how this moment came to be.

In this second letter to Abigail, John Adams describes what he thought the lasting impact, or legacy, of this moment would be for future generations. (He also notes he believes July 2 will be the day of annual celebrations.)

Teacher Directions:

1. Students read letter 1 (or the excerpt of it) and discuss, in pairs or as a class, the inquiry questions:

- According to Adams, what rights do “free and independent States” have?

- He tells Abigail that the Declaration of Independence will lay out the causes that led to it and the reasons that will justify it. Return to the Declaration. Do the writers identify the major causes that led to Independence?

- Adams says “Britain has been filled with folly [foolishness] and America with wisdom”. Where in the Declaration of Independence do the writers list one of Britain’s “follies”?

- What does the Declaration of Independence and John Adams’ private writings tell you about what the writers of the Declaration believed?

2. Students read letter 2 (or the excerpt of it) and discuss, in pairs or as a class, the inquiry question.

- In his letters, Adams emphasizes that the Declaration was adopted unanimously by all colonies. The word “unanimous” is also used to begin the Declaration of Independence itself. Why was unanimity so important to the framers?

- Legacy of the Declaration – Pairs Squared Jigsaw

-

Materials:

Legacy of the Declaration – Pairs Squared excerpts and worksheet

Teacher Directions:

- Place students in groups of 4.

- Each group member will receive an excerpt from one of 4 documents.

- Students read their assigned excerpt independently and write in the provided box how the author is using the Declaration of Independence to argue for the end to slavery.

- Then, each group splits into pairs. Students fill in the box with their explanation and find a connection or pattern between the 2 documents each partner read.

- Repeat the process with the other 2 documents.

- As a group of four, students brainstorm patterns between the 4 documents.

- Finally, synthesize all the documents by answering the question in the center: According to these four sources, what are some of the ways that individuals used the Declaration of Independence to argue for the end of slavery?

Applicable Standards

- C3 Framework for Social Studies Standards

-

D2.Civ.8.3-5. Identify core civic virtues and democratic principles that guide government, society, and communities

D2.Civ.8.6-8. Analyze ideas and principles contained in the founding documents of the United States, and explain how they influence the social and political system.

D2.Civ.8.9-12. Evaluate the social and political systems in different contexts, times, and places, that promote civic virtues and enact democratic principles.

D2.His.3.3-5. Generate questions about individuals and groups who have shaped significant historical changes and continuities.

D2.His.3.6-8. Use questions about individuals and groups to analyze why they, and the developments they shaped, are seen as historically significant.

D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

- MA HSS and ELA Standards

-

Practice Standards

Demonstrate civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence.

Content Standards

Grade 3, Topic 6, Massachusetts in the 18th century through the American Revolution

Grade 5, Topic 2, Reasons for revolution, the Revolutionary War, and the formation of government

Grade 8, Topic 2, The development of the United States government

US History 1, Topic 1, Origins of the Revolution and the Constitution

US Government and Politics Elective, Topic 1, Foundations of Government in the United States

ELA Standards

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text

Additional Resources

Analyzing the Meaning and Legacy of the Declaration of Independence

Additional Primary Sources

- Firsthand Accounts: Hearing the Declaration of Independence be read aloud at the Boston State House, 18 July 1776

-

In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress had adopted the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776, and "published"--publicly announced--it the next day. Express riders carried copies of the first printing of the Declaration to Boston, arriving on 15 July. The Declaration was re-printed in a Salem newspaper, the American Gazette, the following day. On July 18, 1776, Colonel Thomas Crafts publicly proclaimed the Declaration of Independence from the balcony of the Town House (now the Old State House) on King Street in Boston. Below, read the accounts of three Bostonians who were present for the reading.

Letter from Henry Alline to his brother and sister, 19 July 1776 (masshist.org)

The day after the Declaration of Independence was read aloud in Boston, Henry Alline, a clerk living on King Street, wrote to family members. Alline's letter begins with news of his children's recent inoculation against smallpox, and then goes on to describe the public reading of the Declaration of Independence.

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 21 - 22 July 1776 (masshist.org)

On page two of this letter, Abigail describes gathering on King Street to hear the Declaration of Independence as it was read aloud from the balcony of the State House. She begins, "Last Thursday after hearing a very Good Sermon I went with the Multitude into Kings Street to hear the proclamation for independance read and proclamed. Some Field peices with the Train were brought there, the troops appeard under Arms and all the inhabitants assembled there (the small pox prevented many thousand from the Country)."

John Rowe diary 13, 18-20 July 1776, page 2197 (masshist.org)

John Rowe was a Boston merchant. On July 18, 1776, he wrote a short diary entry in which he mentions the public reading of the Declaration of Independence.

Excerpts from all three documents

Read excerpts from the three eye-witness accounts. The google doc also has glossary supports.

- Additional Primary Source Documents at the MHS

-

Declaration of Independence [manuscript copy] handwritten copy by John Adams, before 28 June 1776

Thomas Jefferson shared his earliest drafts of the Declaration of Independence first with John Adams and then with Benjamin Franklin. At an early stage of the revisions, before it was even presented to the Committee of Five, Adams copied the entire document. The Adams copy is extremely important for demonstrating the evolution of the text from Jefferson's "original Rough draught," as he called it, which exists now only as a much marked-up document, to the Declaration so familiar today. (There is no transcription of this document, so you’ll be reading John Adams’ handwriting!)

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America

This broadside was the first printed copy of the Declaration of Independence to list the names of the signers, except Delaware's Thomas McKean, who probably signed the Declaration later. The MHS copy of this document, printed in Baltimore by Mary Katharine Goddard, includes the signatures of John Hancock and Charles Thomson.

Diary of John Adams, Volume 3, [In Congress May—July 1776], p. 335-337

John Adams began writing his autobiography in 1802. He used the diaries, letterbooks, and professional papers he had kept as his sources. In this entry, Adams gives a brief account of the Continental Congress from May-July 1776, which included the drafting and adoption of the Declaration of Independence. He explains, from his perspective, why Thomas Jefferson was chosen to write the document.

Thomas Jefferson Papers : Farm Book

The "Farm Book" is Jefferson's records about his plantation holdings, including Monticello, Shadwell, Lego and Poplar Forest. The volume spans from 1774 to 1824 (with gaps when he was away from Virginia), and contains information about the people he enslaved, planting and harvesting schedules, crop yields, livestock and farm equipment.

Abraham Lincoln to Joshua Fry Speed, 24 August 1855

In 1855, Abraham Lincoln was practicing law in Springfield, Illinois. In 1854, he had lost an election for the U.S. Senate in which he had campaigned in opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In this letter, Lincoln writes to his close friend Joshua Fry Speed about his personal feelings about slavery and the future of the Union should slavery be extended into the new territories. Speed came from a family of enslavers in Kentucky and disagreed with Lincoln's opinions. While discussing political parties near the end of the letter, on page eight, Lincoln references the Declaration of Independence: "As a nation, we began by declaring that "all men are created equal." We now practically read it "all men are created equal, except negroes" When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read "all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics." When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty..."

- Non-MHS primary sources used in the suggested activities

-

To Thomas Jefferson from Benjamin Banneker, 19 August 1791 (archives.gov)

Benjamin Banneker, a free Black man born in Maryland, exchanged letters with Thomas Jefferson in 1791 in an effort to convince the politician that Black individuals were equal to whites, but that the institution of slavery prevented equality.

On 5 July 1852, Frederick Douglass addressed a crowd of white, anti-slavery women in Rochester, New York about the meaning of the fourth of July to enslaved and free African Americans. His speech was later published.

- Additional primary source petitions

-

Just as Prince Hall and other free Black men petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature to end slavery in the state based on their natural rights to freedom, Indigenous people also petitioned state legislatures for land and fishing rights based on their natural rights to their land.

Samson Occom, Petition, to the Connecticut General Assembly, 1785 (dartmouth.edu)

Samson Occom (Mohegan) petitions the CT Legislature on behalf of Mohegan and Niantic fishing rights.

Similar to the above petition, Ocoom wrote this October 1784 petition to the CT Legislature on behalf of Mohegan and Niantic fishing rights, specifically on the Connecticut River. The original petition is held at Connecticut State Library. In addition to the transcription, the Native Northeast Portal has images of the original.

Samson Occom and Montaukett tribe to State of New York, 1780s (Internet Archive)

On pages 10-11 is a petition written by Samson Occom (Mohegan) and addressed to the New York legislature, on behalf of the Montaukett tribe. In the petition, Occom asserts the Montaukett’s natural rights to their land.

This 1775 speech of the Sachem of the Stockbridge Indians is a response to a message sent by the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts.

Digital Resources

This MHS website on the Coming of the American Revolution has a page on the Declaration of Independence: Coming of the American Revolution: Declarations of Independence (masshist.org)

External Institutions

Declaration of Independence: A Transcription | National Archives

From the National Archives: This transcription of the Declaration is made from “the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum.) The spelling and punctuation reflects the original.”

The site also contains additional context about and activities related to the Declaration of Independence.

Series: The Declaration of Independence Through Time (nps.gov)

This article by the National Park Service links to different copies and printings of the Declaration of Independence.

Signers of the Declaration of Independence | National Archives

This spreadsheet lists the names, ages, home states, occupations, and more, of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration of Independence | Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

This resource contains transcripts and audio downloads of the Declaration of Independence; more on Jefferson’s authorship of the document; and, various legacies of the Declaration, at home and abroad.

This article contains additional context and information related to Frederick Douglass’ famous 1852 speech.

“Reading Frederick Douglass Together Discussuion Guide” (Mass Humanities)

This discussion guide includes basic biographical details on Douglass’ life; close reading questions for his speech; links to additional primary and secondary sources; related lesson plans; and, links to picture books on Douglass.

Setting the stage with the colonists’ hostility towards Indigenous peoples in the 1770s (and in the Declaration of Independence), this article examines Stockbridge-Mohicans’ service in the Revolutionary War, their reasons for allying with the Americans, and the ways in which the U.S. government not only failed to honor their contributions, but pushed them off their land and erased them from the story of the war.

Do American Indians Celebrate the 4th of July? | Smithsonian Voices | National Museum of the American Indian Smithsonian Magazine (Dennis W. Zotigh (Kiowa/Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo/Isante Dakota Indian)

This article looks back at the ways in which U.S. government policy (from the Declaration of Independence through the 1930s) existed to take Indigenous land and prevent Indigenous peoples from celebrating their own traditions. Against this backdrop, the author–and many Native commentators –describe how Native peoples have chosen to spend the 4th of July, in the past and today.

This digital exhibit at the Library of Congress contains information on Thomas Jefferson and the drafting of the Declaration of Independence