Massachusetts Historical Society

Collections Relating to the Boston Tea Party

Tangible Connections to the Boston Tea Party

On 16 December 1773, a group of Bostonians disguised as Native Americans boarded three ships docked in the harbor and destroyed hundreds of chests of East India tea, an event now known as the Boston Tea Party. The collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society include items that provide tangible connections to the past and convey the historical context of this significant event. The Tea Act (passed in the spring of 1773) was highly unpopular in the colonies and prompted intense discussions and protests. The Sons of Liberty and other supporters of the patriot cause were prepared to use direct action--including the threat of mob violence--in their long-standing dispute with royal authorities. The destruction of the tea on 16 December 1773 in Boston Harbor was the culmination of weeks of posturing, threats, and counter-threats among the merchants, government officials and radical colonists. [An overview to the Tea Act and the Destruction of the tea in Boston harbor is available.]

While tea was destroyed elsewhere in the American colonies, the town of Boston was singled out for severe punishment. In the aftermath of the destruction of the tea, Parliament passed the "Coercive" or "Intolerable Acts," closing the port and garrisoning the town with thousands of soldiers. The extreme reaction of the British government to the events in Boston galvanized public opinion in the colonies.

Die Einwohner von Boston werfen den englisch - ostindischen Thee ins Meer am 18 December 1773.

Die Einwohner von Boston werfen den englisch - ostindischen Thee ins Meer am 18 December 1773.

See an imaginative--although not wholly accurate--depiction of the Boston Tea Party by a German artist.

Tea leaves in glass bottle collected on the shore of Dorchester Neck the morning of 17 December 1773

Tea leaves in glass bottle collected on the shore of Dorchester Neck the morning of 17 December 1773

Look at a small glass bottle of tea leaves gathered on the shore of Dorchester Neck (across the harbor from Boston) 17 December 1773, the morning after the Boston Tea Party.

Tea, Destroyed by Indians

Tea, Destroyed by Indians

Examine a broadside with rousing stanzas urging citizens to defend their rights

Edes family Tea Party punch bowl

Edes family Tea Party punch bowl

View the punchbowl from which participants in the Boston Tea Party enjoyed libations before heading to Griffin's Wharf on 16 December 1773.

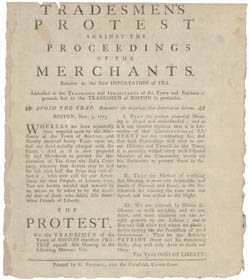

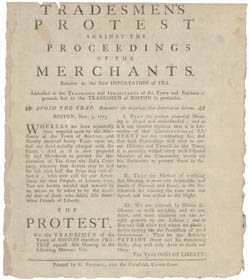

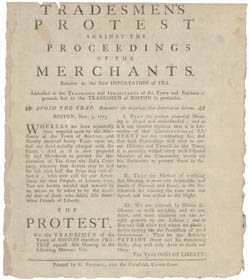

Tradesmen's Protest against the Proceedings of the Merchants ...

Tradesmen's Protest against the Proceedings of the Merchants ...

Consider a broadside published on 3 November 1773 defending the rights of merchants to import British tea, despite other merchants and citizens advocating nonimportation practices.

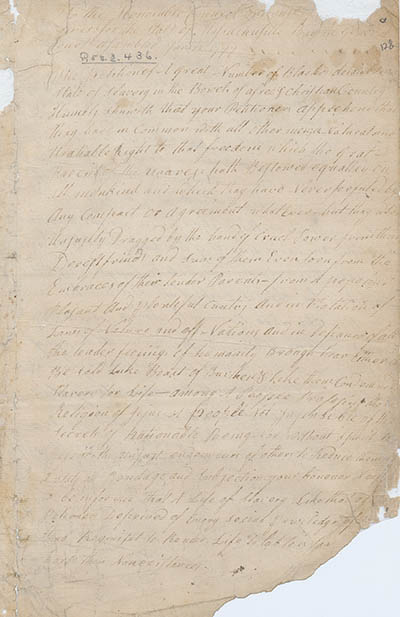

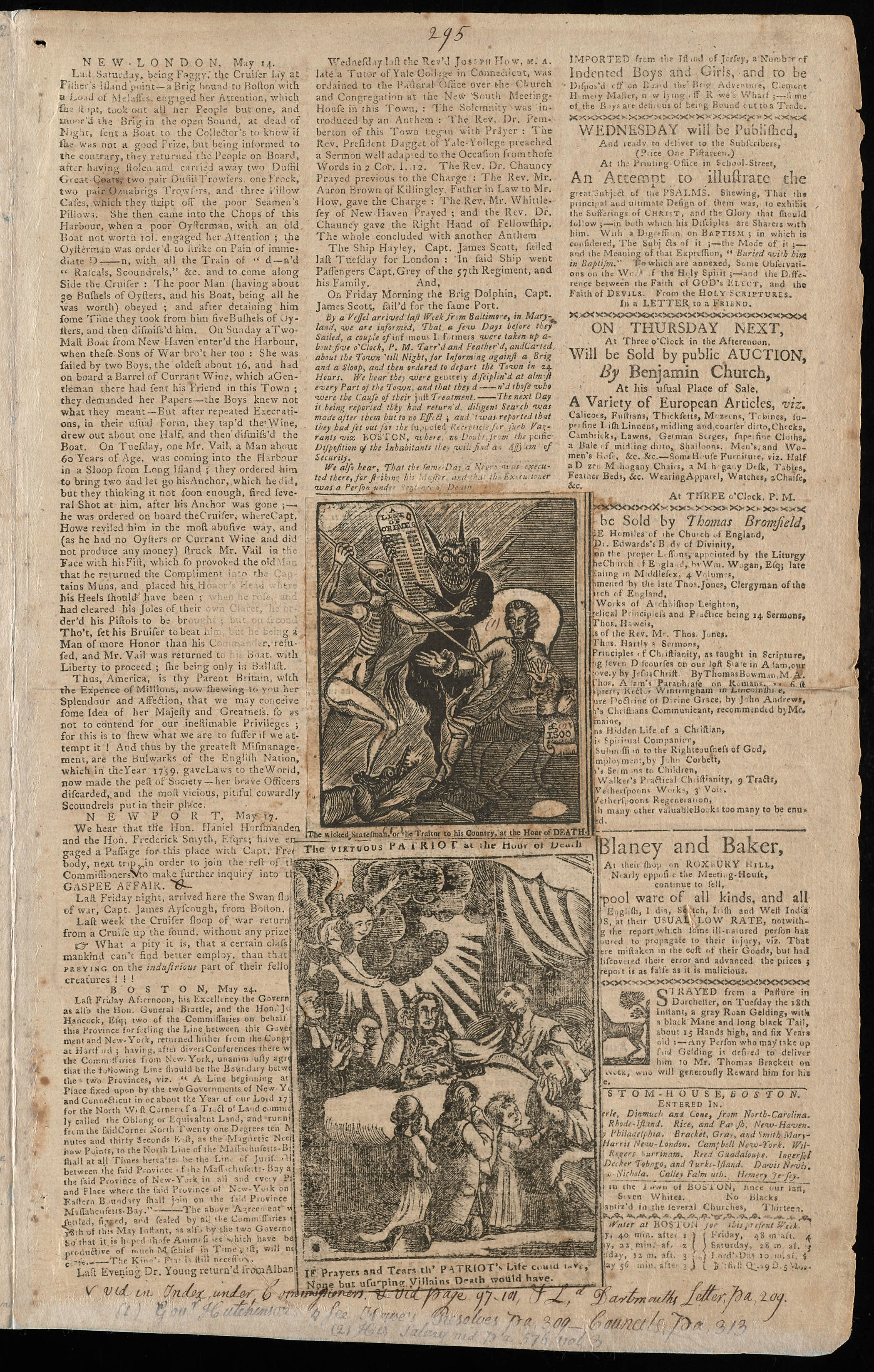

"The following was dispersed in Hand Bills among the worthy Citizens of Philadelphia ..."

"The following was dispersed in Hand Bills among the worthy Citizens of Philadelphia ..."

Read a handbill distributed in Philadelphia and reprinted in a Boston newspaper in October 1773 describing the Tea Act as unjust and urging colonists to refuse shipments of British tea.

Boston, December 1, 1773. At a meeting of the people ...

Boston, December 1, 1773. At a meeting of the people ...

Peruse the account of a town meeting on 29 November 1773 where the townspeople of Boston grappled with how to prevent the unloading, receiving, or selling of the 114 chests of tea that arrived on the ship the Dartmouth.

Boston Tea Party

Related Events Timeline

1763

The Treaty of Paris ends the French and Indian War

1765

Parliament enacts the Stamp Act

1767

The Townshend Acts create a customs commission based in Boston and impose duties on tea, lead, glass, and paper

1768

Boston merchants make non-importation agreements to resist the Townshend Acts; British troops land in Boston to restore order

1770 March 5

The Boston Massacre

1770 April 12

Repeal of the Townshend Acts, except for the tax on tea

1771

Thomas Hutchinson is appointed governor

1772

The Boston town meeting forms a Committee of Correspondence

1773 May 10

Parliament passes the Tea Act

1773 November 3

Sons of Liberty demand resignations of tea consignees

1773 November 5

Meeting at Faneuil Hall resolves to prevent sale of tea

1773 November 28

The arrival of the Dartmouth in Boston with a cargo of the "detested tea" provokes a mass meeting of thousands the next day

1773 December 3

Arrival of the Eleanor, a second tea ship

1773 December 7

Arrival of the Beaver, a third tea ship

1773 December 10

A winter storm wrecks a fourth tea ship, the William on Cape Cod

1773 December 16

Mass meeting at the Old South Church followed by the Boston Tea Party

Additional Context About

the Tea Act and Destruction of the Tea

The Tea Act The seeds of the Boston Tea Party were sown in the spring of 1773, when Parliament passed the Tea Act of 1773 in an attempt to prevent the East India Company from going bankrupt. This act authorized the company to sell a half million pounds of tea directly to the colonies, without paying the usual duties and tariffs. This meant that the East India Company could undersell anyone, including smugglers, whose tea colonists had been drinking almost exclusively since the passage of the 1767 Townshend Acts that placed taxes on everyday items like glass, paper, and tea (all the Townshend Acts except that on tea had been repealed in 1770). Parliament reasoned that if the colonists could buy East India Company tea more cheaply than any other, they would begin drinking it again, thus saving the company. Instead, the act revived the colonists' old argument about taxation without representation and led to the events of 16 December 1773 that later became known as the Boston Tea Party.

Destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor On the night of 16 December 1773, a party of men dressed as Native Americans boarded three vessels--Dartmouth, Eleanor, and Beaver--that were moored at Griffin's Wharf in Boston, intending to destroy their cargoes of East India Company tea. The act was the culmination of many days of posturing, threats, and counter-threats among the merchants, government officials and radical colonists. Incensed at the landing of three ships carrying East India Company tea in late November, colonists had been blocking the unloading of the tea and convening meetings demanding that the tea be returned to England without delay. Earlier that day, a mass meeting at the Old South Church attracted thousands of people from Boston and the surrounding towns. After a day of inflammatory discourse, Governor Thomas Hutchinson's refusal to allow the ships in port to leave without discharging their cargoes of tea was apparently the last straw. Samuel Adams rose, announcing that he did not see what more the inhabitants could to do save their country. At this, war-whoops filled the hall, and between 30 and 60 disguised men, rushed out of the hall and into the streets of Boston, heading for Griffin's Wharf and its three tea-laden ships. In all, 340 large wooden chests containing some 90,000 pounds of tea were dumped into Boston Harbor that night.

Written Reactions and Accounts

Read descriptions and comments about the Boston Tea Party

John Rowe diary 10, 16 December 1773, page 1727

John Rowe diary 10, 16 December 1773, page 1727

See John Rowe's diary entry for 16 December 1773 describing the end of the town meeting and followed by the tea being "flung...overboard."

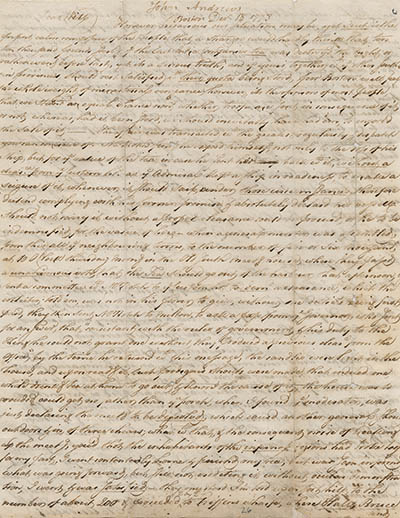

Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 18 December 1773

Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 18 December 1773

Learn about what happened to Captain Conner who ripped open the lining of his coat and waistcoat and filled them with tea during the Boston Tea Party. (Spoiler alert: He was handled "pretty roughly" and stripped of his clothes and given a coat of mud!)

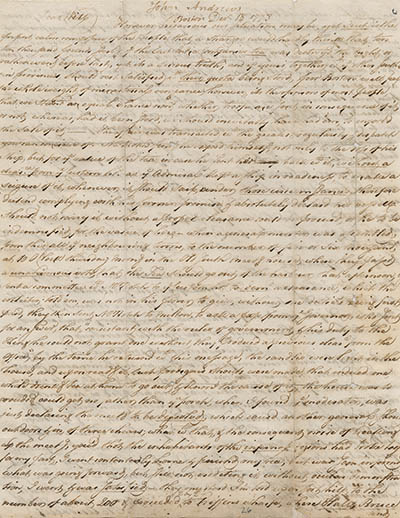

John Adams letter from Adams Papers Digital Edition

John Adams letter from Adams Papers Digital Edition

Read the letter John Adams writes to James Warren the day after the event from the Adams Papers Digital Edition.

John Adams diary from Adams Digital Collection Entry

John Adams diary from Adams Digital Collection Entry

Find out what John Adams thoughts of the destruction of the tea in his diary entry for 17 December 1773.

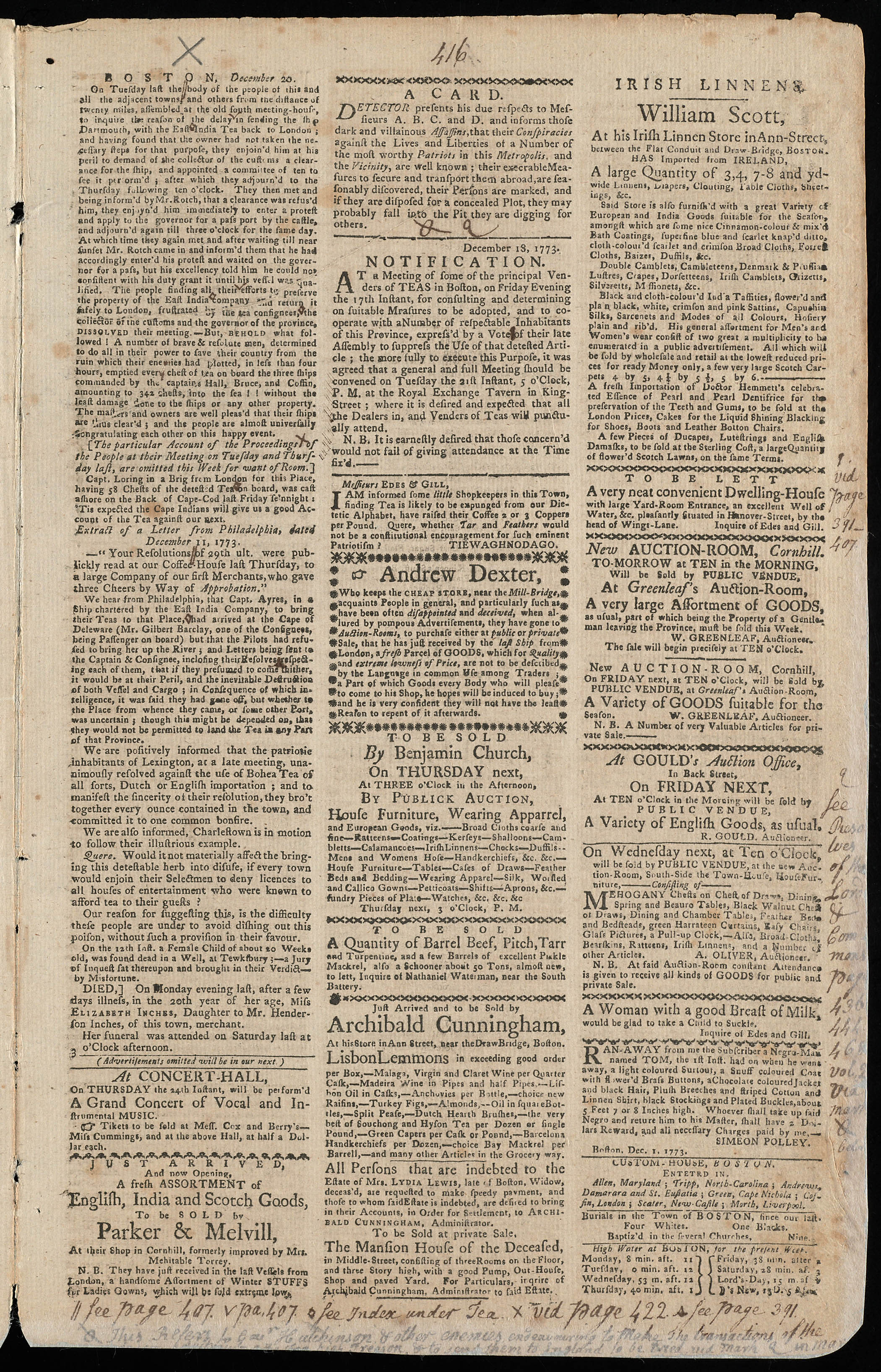

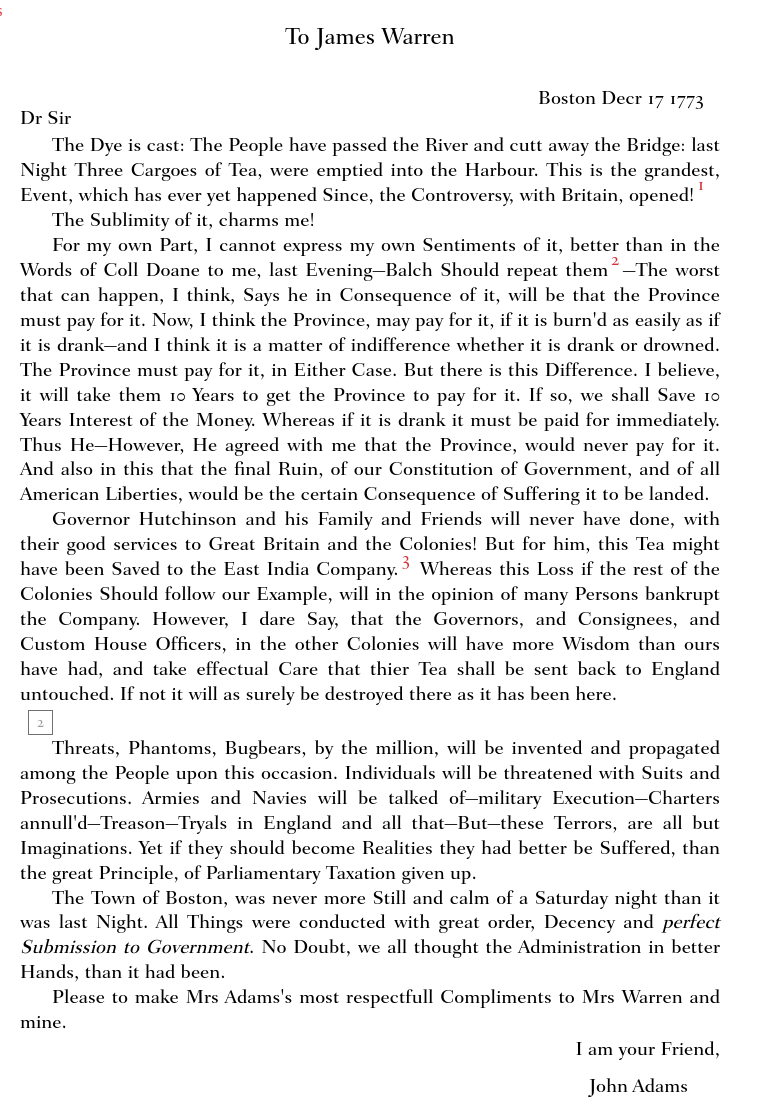

Newspaper from The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Jr.

Newspaper from The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Jr.

Explore a Boston newspaper from 20 December 1773 that includes an article (page 3, column 1) summarizing the town meetings and the aftermath, "A number of brave & resolute men, ... in less than four hours, emptied every chest of tea...." This newspaper is from a collection of annotated newspapers assembled by Harbottle Dorr, Jr., during the years leading up to the American Revolution.

Six Points of View

On the Boston Tea Party

The exhibition, "The Dye is cast": Interests & Ideals That Motivated the Boston Tea Party, is on display at the MHS through 29 February 2024. The exhibition delves into a pivotal moment in American history through the perspectives of six individuals.

Understanding multiple perspectives gives us insight as to why the Boston Tea Party happened. Consider the perspectives of these six individuals: Prince Hall, a free Black man who petitioned on behalf of the enslaved; Joseph Warren, who worked behind the scenes as an opposition organizer; Thomas Hutchinson, the royal governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony; Paul Revere, a silversmith and political propagandist; Phillis Wheatley, a newly emancipated young poet, and John Rowe, a merchant.

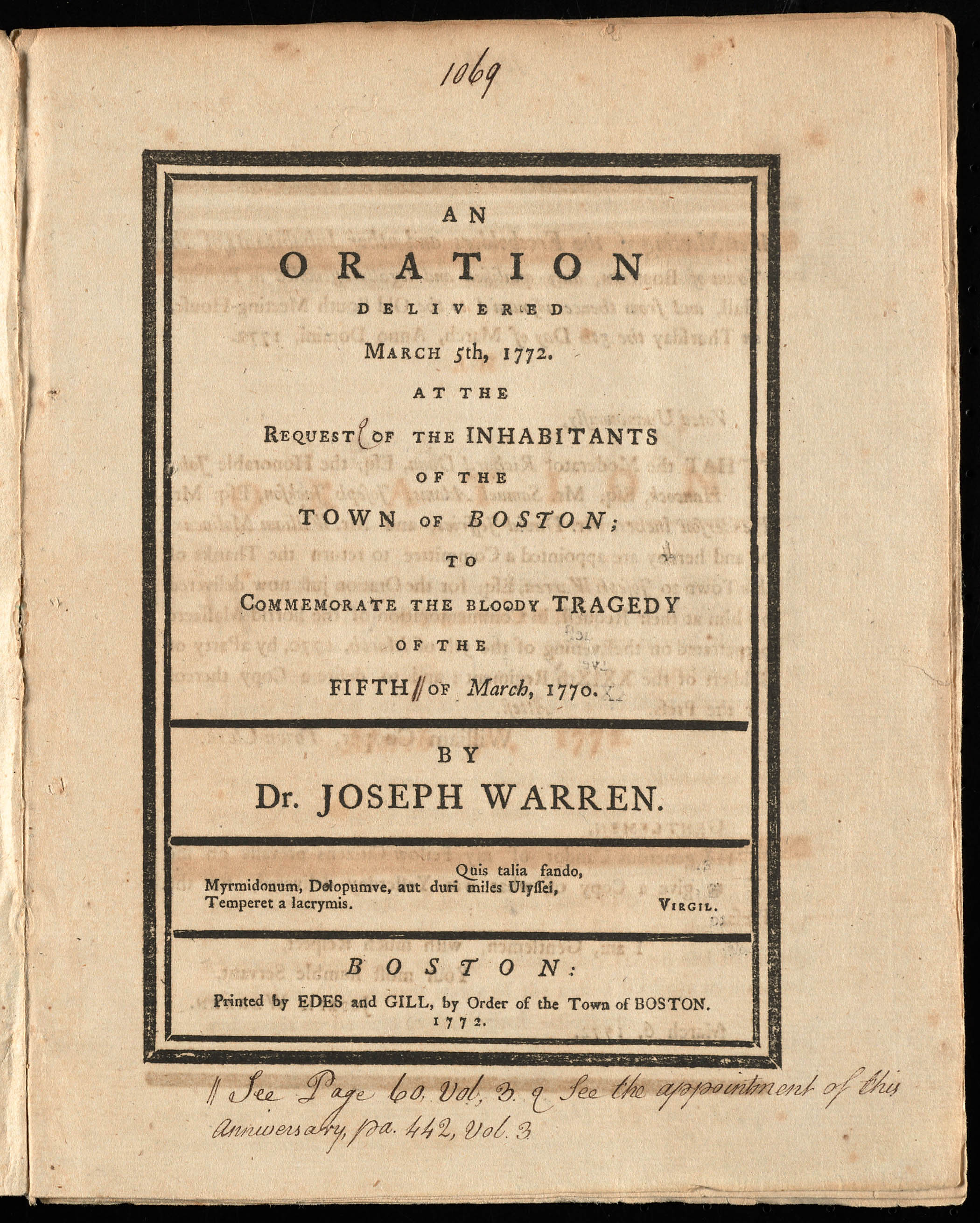

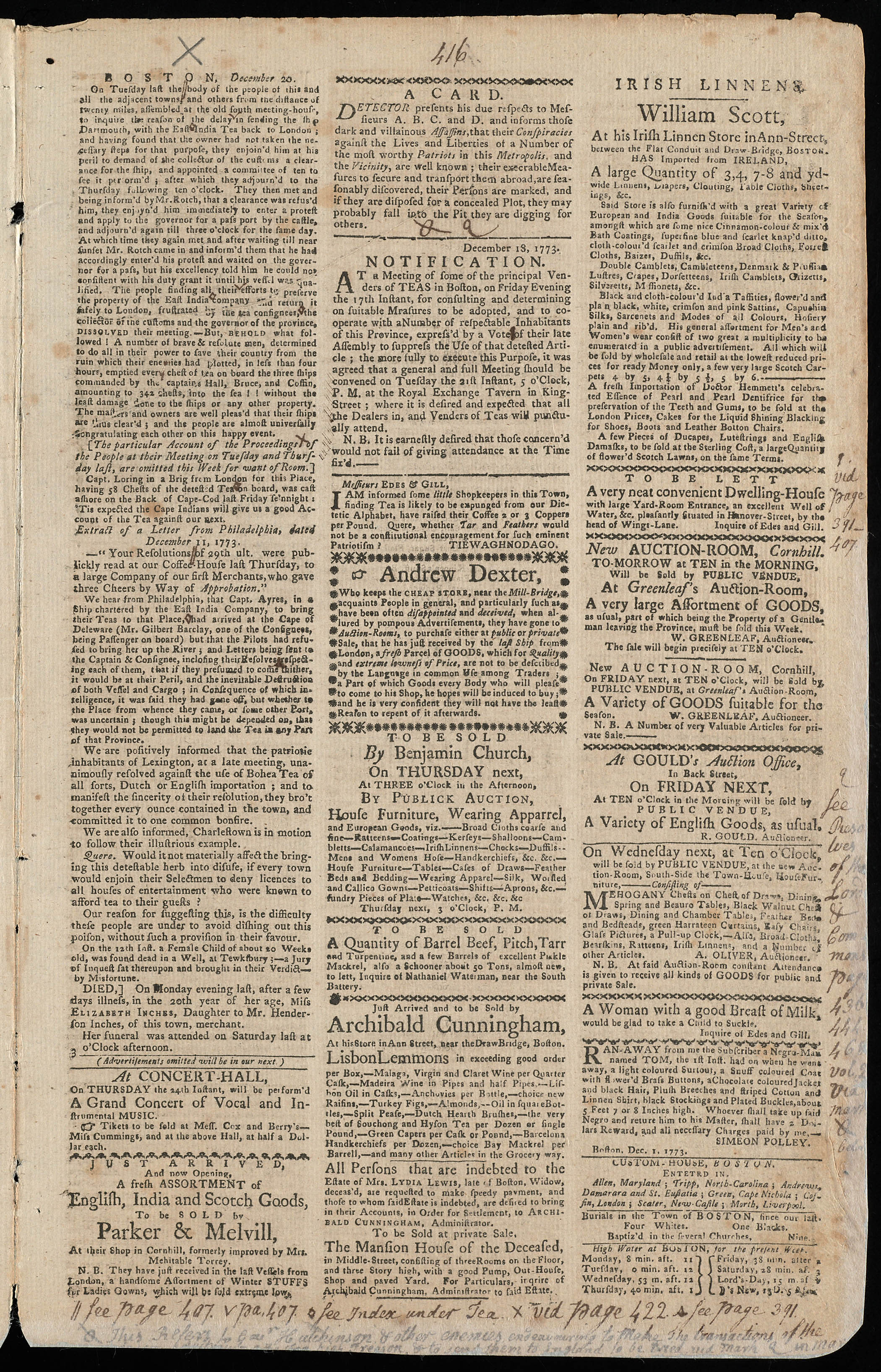

Joseph Warren

In a year of great personal loss--Joseph Warren's wife Elizabeth Hooten Warren, the mother of four young children, died in May 1773--he strove to maintain a balance between resisting unjust royal authority and preventing mob violence. In this effort he drew upon a large network of political and masonic connections.

After the Tea Party April 1775, Dr. Joseph Warren was elected president of the provincial congress. In June 1775, he was killed fighting as a volunteer, at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Featured Item

Published version of Dr. Joseph Warren's Oration delivered on the second anniversary of the Boston Tea Party.

Published version of Dr. Joseph Warren's Oration delivered on the second anniversary of the Boston Tea Party.

Also in MHS's Collection

Sword said to have belonged to Gen. Joseph Warren

Sword said to have belonged to Gen. Joseph WarrenGovernor Thomas Hutchinson

Born in Boston, Thomas Hutchinson was the royal governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. A talented colonial historian, Hutchinson looked to the past to guide the policies of the parliament. He recommended conciliatory measures in the face of colonial resistance but argued for a firm commitment to the final authority of the royal government.

After the Boston Tea Party: Governor Thomas Hutchinson left American for consultations with King George in 1774. he never returned to America and he died in exile in 1780.

Paul Revere

Paul Revere was a talented silversmith and an active member of many political groups and fraternal organizations including being a Freemason for more than 50 years. He combined his political interests and artistic talents as a prolific engraver of satirical cartoons. He made the first of his famous "revolutionary rides" on 17 December 1773 when he set out to carry the "glorious news" of events in Boston to New York and Philadelphia.

After the Boston Tea Party: the Revolution, Paul Revere spread his wings as a business entrepreneur. At the time of his death in 1818, the revolutionary generation was rapidly fading away.

Also in MHS's Collection

Letter from Paul Revere to Jeremy Belknap, circa 1798

Letter from Paul Revere to Jeremy Belknap, circa 1798 Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

Phillis Wheatley

In September 1773, Phillis Wheatley returned from a trip to England, where she had been greeted as a literary celebrity, her poems had been published to considerable acclaim, and her emancipation from slavery had been secured. She arrived just as news of the Tea Act reached America. The cargo of the Dartmouth, the first tea ship to arrive in Boston, included copies of her recently published poems

After the Boston Tea Party: Phillis Wheatley married John Peters, a free Black man, in 1778. A celebrated figure in 1773, she died in obscurity in 1784. The manuscript of a second volume of her poems has been lost.

Also in MHS's Collection

Phillis Wheatley's writing desk

Phillis Wheatley's writing deskJohn Rowe

Moderate in all things, merchant John Rowe tried to balance his business interests with his political sympathies. He was the owner of one of the ships that brought East India tea to Boston and, at the same time, an active participant in the Protest meetings that led to the Tea Party. A prolific diarist, he may have "moderated" his record of his role in public events.

After the Boston Tea Party: John Rowe remained in Boston during the Siege but did not leave when the British evacuated the town in 1776. By 1779, Rowe had returned to a position in town government. He died in 1787.

Featured Item

John Rowe diary 10, 16 December 1773, page 1727

John Rowe diary 10, 16 December 1773, page 1727Also in MHS's Collection

"Summary of the Cargo of the Snow Pittt [sic] ..."

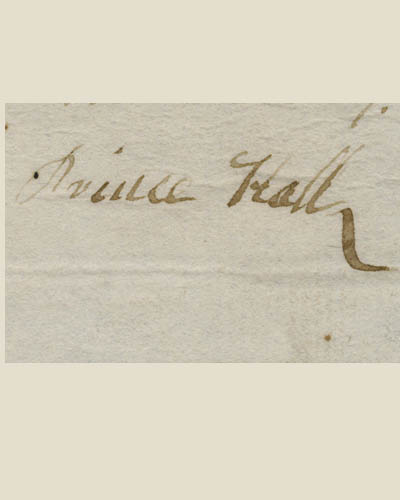

"Summary of the Cargo of the Snow Pittt [sic] ..." Prince Hall's signature from a manuscript bill

Prince Hall's signature from a manuscript bill

[Note: At this time there is no known image of Prince Hall.]

Prince Hall

Prince Hall, a Black man who was emancipated in 1770, began petitioning first the colonial and later the revolutionary government to end slavery in Massachusetts. He also wanted to open the brotherhood of freemasonry to Black men. Hall's actions demonstrate that the struggle for freedom was more complex than simply resistance to royal authority

After the Boston Tea Party: Prince Hall continued to petition for the abolition of slavery. In 1775, he turned to a masonic lodge of British soldiers to be initiatied into freemasonry. He died in Boston in 1807.

Explore More

- The Coming of the American Revolution, an online collection of primary sources and contextual essays for educators and learners, includes a section on The Boston Tea Party

- The manuscript collection, John Greenough papers, contains papers relating to the sale of East India Company tea that was recovered from a vessel, the William that was shipwrecked off the coast of Cape Cod. The small collection has been has been fully digitized and every page can be viewed online.

- The Papers of John Adams, volume 2 (digital edition), contains the letter John Adams sends to James Warren on 17 December 1773 describing the destruction of the tea as "the Grandest Event, which has ever yet happened Since, the Controversy, with Britain opened!"

- Precious Cargo: Phillis Wheatley's Poems and the Boston Tea Party is MHS's Object of the Month web feature about a letter Wheatley sends to David Wooster in October 1773 mentioning the imminent arrival of copies of her book of poetry. It turned out that the Dartmouth, the vessel carrying crates containing her book of poems, also carried crates of tea in its cargo hold.

- Revolutionary-era newspapers may be explored within a digital collection, The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Jr. Dorr was a shopkeeper in Boston who collected, annotated and indexed over 800 newspapers during the years leading up to the American Revolution.