Collections Online

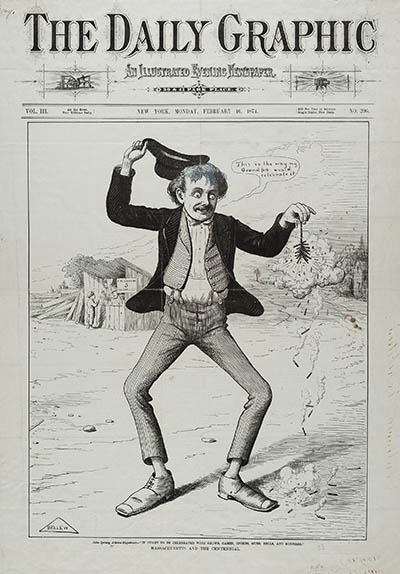

John Quincy Adams (loquiteur) : "It ought to be celebrated with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, and bonfires." Massachusetts and the centennial

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Object of the Month ]

This cartoon by Frank Bellew in the New York Daily Graphic lampoons a February 1874 speech of John Quincy Adams II (1833-1894) in the Massachusetts House in which he tried to assert that the upcoming centennial Fourth of July should be celebrated just as his great-grandfather had prescribed in 1776, rather than with the huge industrial exhibition that was then being planned. Adams—as in his many runs for governor of Massachusetts—did not prevail.

Who was John Quincy Adams II?

Named for his grandfather, the sixth president of the United States, John Quincy Adams II was born in Boston to diplomat Charles Francis Adams and his wife Abigail Brown Brooks on 22 September 1833. He graduated from Harvard with the Class of 1853 and practiced law for a time, a career that his obituary noted he was “never overfond of.” He established a model farm in Quincy and devoted himself to local and state politics. Although he began political life as a Republican and staunch supporter of Lincoln, he broke ranks with the party over their reconstruction policies. As a Democrat, he ran unsuccessfully for governor every year from 1867-1871 and served four terms as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from Quincy, and in many other local offices. His New York Times obituary eulogized him as a man “of exceptional ability, of sterling character, strong parts, independence of thought and spirit, of good training and sound judgment … [whose] political opinions … were always peculiarly his own.”

Guns, bells, and bonfires

The story behind this cartoon began on 3 July 1774, when John Adams, a delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, wrote to his wife, Abigail, about the vote to declare independence from Great Britain, asserting

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.—I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by Solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be Solemnized with Pomp and Parade with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

Although the date of the celebration would be the fourth of July, rather than the second, John was prescient about the mode of celebration, although his great-grandson apparently believed that “from this Time forward forever more” meant just that—even for the milestone 100th anniversary.

In the Massachusetts House

The Boston Daily Advertiser of 8 February 1874 carried this brief notice of legislative activity:

The House had a field day on Saturday, being in session about three hours and having two pretty lively discussions. John Quincy Adams made an attack, in his characteristic style, on the centennial resolution, or rather on the centennial itself, which he stigmatized as merely a glorification of the almighty dollar. The house listened to his speech with attention, but with what degree of approval cannot be told, as the subject was laid over with very few more words. Mr. Crocker of Boston, however, took occasion to say that he would be ashamed to make such a speech as that of Mr. Adams.

Although the full text of this speech has been elusive, newspapers across the country picked up on it and used it to further their own agenda regarding the exposition. The Daily Graphic, obviously, opposed Adams’s views in their description of the cartoon:

Mr. John Quincy Adams has made a speech, setting forth his objections to celebrating the Centennial with an International Industrial Exhibition. He quotes with admiration the saying of his illustrious great-grandfather … and insists that the Centennial, which is only a Fourth of July of larger growth, should be celebrated in the same way. The cartoon on our first page represents Mr. Adams actively engaged in celebrating the Centennial according to the Adams prescription. The enthusiasm with which he watches the noisy explosion of a pack of fire-crackers and waves his hat in honor of our nation’s birthday is very evident, but, with the exception of a small-boy who is negotiating for fire-crackers at a distant shop window, Mr. Adams is as solitary as he is when running as the Democratic candidate for the Governorship of Massachusetts. He will find few persons except depraved small-boys to applaud his method of celebrating the Centennial …

The Milwaukee Daily Sentinel of 20 December also came out strongly against Adams writing, “it is to be hoped that the apathy, not to say hostility, of the Massachusetts Legislature … will not be generally imitated throughout the country … Action … was postponed for the reason that old John Adams, our second President, once said something which has been tortured by his ingenious great grandson … into an opposition to anything but bonfires and firecrackers.”

The Cincinnati Gazette (quoted in the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean) agreed with Adams, saying that the exhibition “is all well enough” but “nobler principles than mere business shrewdness and mechanical skill … should accompany our republic’s notification to the world that she has entered upon the second century of her existence.” In the same article, however, the Daily Inter Ocean questioned whether John Quincy Adams was “not so dazed by the halo around the memory of his distinguished relative as to be blinded to the actualities of the present time” and suggesting that, if John Adams were still around, even he would have modified his views on the proper mode of celebrating the centennial to be in “closer consonance with the spirit of the age.”

His father may also have disagreed

Interestingly, at the same time that John Quincy Adams spoke against the centennial exhibition, his father Charles Francis Adams had just submitted his report on the 1873 Vienna Exposition. Critical of many facets of the exposition, Adams noted that in planning for our country’s centennial, organizers should “not lose a moment … The legislatures now in session should decide on the course to be pursued and not swerve from that decision whether it be to do something or nothing.” Rather than “a glorification of the almighty dollar,” Charles Francis Adams saw great potential in the commercial aspects of a centennial exhibition, as noted in the 7 February 1874 Boston Daily Advertiser

The mercantile element, however, which have proved the great main spring of all recent expositions will there be present in a more than ordinary degree. Throughout the civilized world America is known as a great market, as a market in which fabulous prices are paid … Accordingly all the leading producers of the world … will wish to be represented …

The Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition

Despite the protestations of John Quincy Adams II, the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine opened to the public on 10 May 1876, running through 10 November and attended by more than 10 million visitors. Massachusetts had its own building highlighting the arts, institutions, and industries of the Commonwealth.

For further reading

The newspaper articles cited here can be accessed through Gale’s Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, available to cardholders through the Boston Public Library’s website.

Massachusetts. Centennial Commission. Report of the Massachusetts Commissioner to the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia Boston: Albert J. Wright, 1877