Collections Online

Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 18 December 1773

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Object of the Month ]

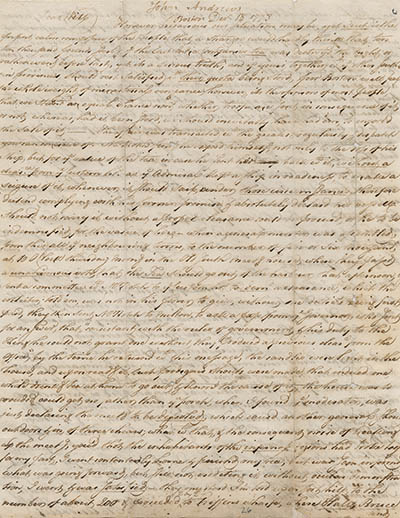

On the evening of 16 December 1773, John Andrews, a young Boston merchant, after finishing his tea at his home on School Street, set out for the waterfront to have an “ocular demonstration” of “what was going forward” at Griffin’s Wharf—the destruction of the East India Company tea that we know today as the Boston Tea Party. Two days later, Andrews wrote a “more particular account” of the events he witnessed in a letter to his brother-in-law William Barrell, a merchant in Philadelphia.

Who was John Andrews?

John Andrews was born in Boston in 1743, a son of John and Hannah Andrews. The younger Andrews began his career as a merchant before the Revolution and later ran a hardware business on Union Street in Boston. In 1771, he married Ruth (often, sometimes even in official documents, “Ruthy”) Barrell, born in 1749. Ruthy and John had four children born during and after the Revolution. John Andrews’s correspondence with Ruthy’s brother William, who was born in Boston but worked as a merchant first in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and later in Philadelphia, extended from 1771 until William’s death in 1776.

A more particular account

John Andrews’s engaging letters to William Barrell, rediscovered in Philadelphia during the Civil War, provide a detailed account of political and military affairs—and everyday life—in Boston before and during the Revolution. The letters have been cited in published accounts and more recently on websites, but often from an extended “digest” of them published by the Massachusetts Historical Society soon after their discovery.

The destruction of the “banefull herb”

In his 18 December letter, John Andrews gave his brother-in-law (and modern readers) a detailed description of what became known during the 19th century as the Boston Tea Party. He wrote of “the affair” on the evening of 16 December as having been “transacted with the greatest regularity & dispatch.” His estimate of the number of people “mustered” for meetings in the Old South Meeting House that day (five or six thousand) seems fantastic but less than Samuel Adams’s estimate of seven thousand. Ironically, Andrews reported that he was at home having tea when he heard the tumult as the public meeting dissolved and went to see “what was going forward,” but returned home to “contentedly” finish his repast before proceeding to Griffin’s Wharf to observe the destruction of the “ill-fated” cargos. “Before nine O Clock in ye eveng,” he wrote, “every Chest, from on board the 3 vessells, was knocked to pieces and Flung over ye sides.” Andrews speculated that the “Indian” disguise of the “actors” who destroyed the tea was that of members of the local Narraganset tribe, and that their “jargon was unintelligible to all but themselves”—and concealed their plans and preparation.

He also described the rough justice dealt out to an Irish immigrant, “one Capt Conner,” who had attempted to conceal tea stolen from the cargo in the “ript” lining of his coat—a memorable scene that, with other details of the Tea Party, was integrated into the plot line of Esther Forbes’s historical novel, Johnny Tremaine.

"The weather as yet, continues wth us very mild & at the same time very unhealthy"

The John Andrews letter ends with more domestic and personal news from Boston, what often is missing from descriptions of political and public events. An inflammatory fever “prevailed much” in Boston, striking down and killing young and otherwise healthy people, but after three weeks of illness, Andrews’s wife (Bill Barrell’s sister) “dear Ruthy,” was deemed on the path to recovery.

The complete text of Andrews’s 18 December letter to Barrell was—and remains—difficult to decipher. It is filled with the author’s idiosyncratic contractions, abbreviations, and underlining of names and words, perhaps written in haste to get the “particular account” onto two sides of a single sheet of paper and off in the post to Philadelphia. If so, Andrews was not entirely successful in his plan and had time and space to add two postscripts (at right angles to the original text) on the covering sheet where the letter was addressed.

In the addenda, Andrews reported the wreck of a fourth tea ship on Cape Cod, making the total number of tea chests destroyed four hundred, but also reported that the brig William, the tea ship that never arrived, also had been carrying streetlamps to illuminate Boston (the cargo of both lamps and tea later was salvaged). In a second addenda about business matters, Andrews noted news already received from Philadelphia of the peaceful, but successful resistance to the importation of tea there.

Phillis Wheatley and dinner for General Washington

John Andrews continued to provide William Barrell with a description of life in Boston before and during the first year of the Revolution. Both men (and Ruthy Andrews) were interested in Phillis Wheatley, the young Black poet who lived in Boston. John and William were impatient to see the publication of Wheatley’s poems, while Ruthy was a poet in her own right. While not mentioned in the 18 December letter, newly published copies of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral were part of the cargo of the Dartmouth, one of the ships that brought East India tea to Boston.

John Andrews remained in Boston during the siege (1775–1776) to protect his own property and that of other merchants, but he did not leave with the British forces and loyalists when they evacuated the town—just the opposite, as he related to William Barrell, on short notice he hosted General George Washington and his entourage (including Martha Washington) for a dinner in April 1776.

After the Revolution, the Andrews family lived in an elegant Winter Street house near Boston Common, surrounded by gardens that were a “public benefaction.” John Andrews was the proprietor of a hardware business and served as a selectman and town officer. John and Ruthy later moved to Jamaica Plain, a countrified neighborhood of Roxbury, outside of Boston. John Andrews died there in 1822 at the age of eighty; Ruthy lived on at their country home until her death in 1831.