Collections Online

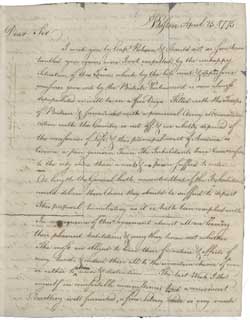

Letter from Andrew Eliot to Thomas B. Hollis (copy), 25 April 1775 and letter from Andrew Eliot to unidentified recipient (draft), 31 May 1775

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- Siege of Boston

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Object of the Month ]

These letters dated April and May 1775 from Rev. Andrew Eliot of Boston to Thomas Hollis and an unidentified recipient describe the conditions in Boston during the early days of the Siege of Boston.

“The unhappy Situation of this Town”

Less than a week after the opening salvos of the Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord, Andrew Eliot, minister of the New North Church in Boston, wrote to his friend Thomas Brand Hollis about the rapidly deteriorating conditions in the town of Boston. “Filled with the Troops of Britain & surrounded with a provincial Army, all communication with the Country is cut off, & we wholly deprived of the necessaries of life,” Boston had become “a poor garrison Town.” Filled with dread, yet bearing a responsibility toward his flock, Eliot sent his wife and children away from the town as soon as it became possible and hunkered down to tend to the spiritual needs of those remaining. The letter to Hollis predicts in no uncertain terms that the colonists were ready to fight and that “Great Britain may ruin the Colonies, but she will never subjugate them” and that the contest would end in a “total Separation of the Colonies from the Parent Country.”

“I have remained in this Town much agt: my inclination”

In a draft letter to an unknown recipient written on page four of Eliot’s letter to Hollis, he writes of further developments. His family gone, himself one of only a few ministers left in Boston, Eliot describes his situation as “uncomfortable to the last degree.” After the Battle of Bunker Hill in June, Eliot worked with sick and wounded prisoners and tended to civilians who were dying of heat, malnutrition, and disease in the besieged town. Finally, in September of 1775, Eliot had seen enough and applied for a pass to leave Boston, which was denied by the authorities. He steeled himself and remained for the duration of the British occupation. After the British finally evacuated Boston on 17 March 1776, George Washington asked Eliot to preach the Thanksgiving sermon on 28 March 1776 (a sermon on Boston during the Siege, which unfortunately, does not survive). Privately, Eliot wrote to Isaac Smith, “We have been afraid to speak, to write, almost to think. We are now relieved, wonderfully delivered … Independence, a year ago, could not have been publicly mentioned with impunity. Now nothing else is talked of.” He would not live to see American independence come to fruition, however.

“Hutchinson’s parish priest and his devoted idolator”

Bernard Bailyn wrote that in the years leading up to the Revolution, Eliot “had learned to avoid public polemics, to seek comfortable middle-of-the-road positions on difficult current issues, and, as much as a consequence of natural geniality as of principle, extended the hand of fellowship to those who differed with him.” This tendency was entrenched in him, perhaps due to the experience of his grandfather (also named Andrew) who had served on the Salem witchcraft jury in 1692 and harbored regrets about its actions for the rest of his life. Unfortunately, in the early days of the Revolution, this balancing act made Eliot suspect to Patriots and Loyalists alike. John Adams rebuked him as “[Thomas] Hutchinson’s parish priest and his devoted idolator,” for his friendship with the hated governor; in 1772, Ezra Stiles echoed this, referring to him as “Andrew Sly, who oft draws nigh To Tommy’s skin & bones” in his description of the Boston ministers’ views of liberty. During the Siege, Eliot’s ministrations to revolutionary James Lovell got him banned from the prison where he had been caring for the sick and wounded and cost him the friendship of some Boston Loyalists.

Who was Andrew Eliot?

Andrew Eliot was born in Boston in 1718, the son of cordwainer Andrew Eliot and his wife Ruth Symonds. He graduated from Harvard with the Class of 1737 and received his masters degree from the College three years later. In 1741, he was invited to preach as a candidate at the New North Church and accepted the call to the pulpit in February of 1742. Later that year, he married Elizabeth Langdon, the daughter of Deacon Josiah Langdon of the New North Church, and together they had a family of 11 children. In 1756, he bought a house at Hanover and North Bennet Streets in the North End neighborhood of Boston which had been built by Rev. Increase Mather in 1677.

Eliot died on 13 September 1778 after a brief illness and was honored by a funeral procession half a mile long. He was buried at Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in the North End of Boston. His son John was called to succeed his father in the pulpit of the New North Church and was later one of the co-founders of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

For further reading

Bailyn, Bernard. “Religion and Revolution: Three Biographical Studies,” in Perspectives in American History, vol. 4 (1970), p. 85-169

Shipton, Clifford K. “Andrew Eliot,” in Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College in the Classes 1736-1740, p. 128-161. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1958

Sprague, William B., “Andrew Eliot,” in Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 1, p. 417-421. New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1857.

Thacher, Peter. The Rest which remaineth to the People of God, and the Character of such as shall enjoy it, shewn in a sermon preached at the New North Church in Boston, September 13, 1778 : Being the Day of the Death of Their excellent Pastor Andrew Eliot, D.D. Boston: Printed by Thomas and John Fleet, 1778.