Collections Online

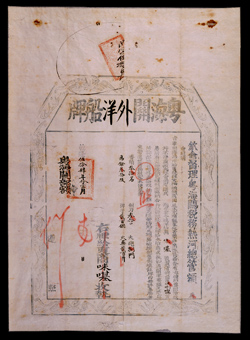

Grand chop of the ship Astrea, January 1790

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- MHS 225th Anniversary

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Witness to America's Past ]

All foreign traders approaching Canton, the only port open to international trade before 1840, were obliged to observe a complex series of customs and formalities. When a ship reached the Portuguese colony of Macao, a permit and pilot were secured to take the ship to Whampoa on the Pearl River, the anchorage for Canton, beyond which foreign ships were not allowed to progress. The ship and its cargo then had to be sponsored by one of the co-hong, a group of usually twelve senior merchants who paid a substantial fee to the emperor for a monopoly on all international trade. The shipmaster or supercargo in charge of the ship's cargo employed a linguist, or custom-house clerk, to manage all transactions and communications between the custom house officers and the foreign merchant, and a comprador was hired to act as steward and purser for the ship and the merchant's household. At Whampoa the Hoppo (superintendent of customs) or his deputies came aboard to receive presents and measure the ship for taxes. Finally, the merchandise was transported upriver in sampans (lighters) to Canton. It was there stored in a "factory" or warehouse hired from one of the hong merchants, who oversaw the trade procedures.1 The strange laws and customs of Chinese trade led to the creation of Boston mercantile agencies at Canton to ease the way for American traders. The first of these was Shaw and Randall, established by Major Samuel Shaw of Boston in 1786.2

The formalities for shipping cargo out of Canton were similarly complex. Permits or "chops" were issued at Canton, examined and countersigned at Whampoa; dues, fees for pilotage, and bribes were paid, and when all was in order, the final Canton port clearance, or "Grand Chop," was issued to the ship. Everything with a government stamp or seal became known as a chop to foreigners, and this was the grandest of them all, "a formidable-looking document . . . ornamented with curling dragons."3 This document enabled ships to depart from the Whampoa anchorage and continue down river.

The grand chop shown here was issued to the Salem ship Astrea, whose supercargo Thomas H. Perkins kept a journal of part of the voyage to China in 1789, and who retained this document. The Astrea obtained her grand chop in early January 1790, but was so overloaded with cargo and extra crew that she delayed her departure from Whampoa until January 22 so as to build an extra shack on deck to shelter the men.4

The grand chop states that all proper duties have been paid for the ship and should not be required again if the ship is driven into another port by contrary weather. It also lists the number of crew members, swords, cannons, guns, bullets, and gunpowder aboard ship, and the date of issue.5

George Edward Cabot, the donor of this document, was the great-grandson of Thomas Handasyd Perkins. He gave a large collection of T. H. Perkins papers to the Society, as well as papers of another China Trade merchant, Samuel Cabot, Perkins's son-in-law.

1. Kenneth Scott Latourette. The History of Early Relations between the United States and China, 1784-1844. New York: 1964, pp. 22-23; Samuel Wells Williams. The Chinese Commercial Guid. 5th ed. Hong Kong, 1863, pp. 160-161.

2. Samuel Eliot Morison. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860. Boston, 1921, p. 66.

4. Richard H. McKey, Jr. "Elias Hasket Derby and the Foundingof the Eastern Trade (Part II)." Essex Institute Historical Collections 92 (1962), p. 77.

5. Williams 1863, p. 168; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Asiatic Department translation, 1990.