Collections Online

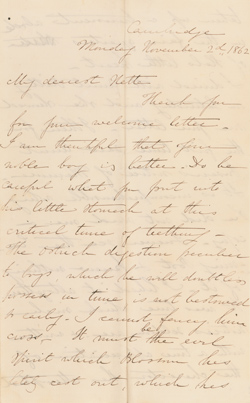

Letter from Elizabeth Sedgwick Child to Henrietta Ellery Sedgwick, 2 November 1862

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Civil War ]

In this chatty letter to her sister Henrietta, Elizabeth Sedgwick Child writes with family news, sisterly advice, and a description of her recent charitable work cutting material to be made into “picturesque” suits for slave women seeking refuge with the Union Army.

Elizabeth Sedgwick Child was born into the prominent—and expansive—Sedgwick family in 1824. In 1860, she married Francis J. Child, an intellectually gifted and well respected Harvard professor. The couple settled in Cambridge, and together had four children: Helen, Susan, Henrietta, and Francis. Elizabeth Sedgwick’s sister, Henrietta Ellery Sedgwick (“Netta”), lived in Stockbridge with her two young children, three-year-old Jane and infant Henry III, referred to in this letter as “Blossom,” and “your noble boy.” Throughout the letter Elizabeth mentions several other family members including her sister, Katherine (“Kate”); Henrietta’s husband, Henry II (“Hal”); and her mother, Elizabeth Ellery Sedgwick, who died on 6 September 1862.

After some discussion of Netta’s children and the death of her mother, in the final pages of this letter Elizabeth describes her recent exertions “cutting petticoats & sacks for the contrabands” (page 5). Although her description of her efforts may seem rather frivolous, focusing on turning “gay material, once window curtain” into a “picturesque suit,” (page 6) her work supported a serious cause, providing relief to slaves who sought freedom and refuge with Union forces over the course of the war. The status of these men and women was ambiguous. Early in the war Union General Benjamin Butler applied the term “contraband” to these men and women to justify not returning the escaped slaves to their southern masters. While the passage of the Confiscation Act later in 1861 rendered the term contraband obsolete, it remained the popular phrase for describing the refugee slaves living in camps within proximity of Union forces throughout the war.

Elizabeth’s husband, Francis Child, was among the first members of the Boston Educational Commission for Freedmen, the precursor to New England Freedmen’s Aid Society. Formed in February 1862, the Commission worked to provide for the industrial, social, intellectual, and religious development of former slaves released over the course of the war. Francis Child served on the Commission’s Committee on Correspondence, which was responsible for coordinating local efforts with the work of the federal government and Union Army.

As demonstrated in this letter, Elizabeth Child contributed to the Commission’s work as well. The Commission was initially confronted by a lack of basic supplies, including food and clothing, for the men and women they hoped to aid. The federal government was providing foodstuff, but the Commission was dependent on private charity for donations of clothing. Elizabeth was one of many women throughout Boston cutting donated fabric, some of which they donated themselves, in November of 1862. The fabric they cut was subsequently sewn into garments by seamstresses throughout the city. It is likely that, when finished, the practical “petticoats & sacks” Elizabeth cut were sent to the Port Royal area in South Carolina, as the Educational Commission worked to support the Port Royal Experiment throughout 1862.

Over the course of the war the Boston Educational Commission for Freedmen evolved into the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society. Originally intent on supporting the efforts in Port Royal, the organization rapidly expanded its scope, sending teachers and other necessities to the South. At the end of the war, the Society worked alongside the federal Freedmen’s Bureau, continuing the work of providing education for freedmen.

Sources for Further Reading:

The letter featured here is one of many Civil War era documents contained in the multigenerational Sedgwick Family Papers. In addition to letters concerning the relief work of various family members, there are also letters detailing the Civil War service of Elizabeth Sedgwick Child’s cousin William Dwight Sedgwick (1831-1862). Included among those is a moving letter written by William’s wife, Louisa Frederica Tellkampf Sedgwick, after William’s death at the battle of Antietam in September 1862.

The MHS also holds a small collection of the records of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society, containing a volume of meeting minutes including activities of the Boston Educational Committee.

Educational Commission for Freedmen (Boston, Mass.). The Clothing Committee of the Educational Commission Ask …. [Boston: s.n., ca. 1862].

Educational Commission for Freedmen (Boston, Mass.). First Annual Report of the Educational Commission for Freedmen. Boston: David Clapp, 1863.

Ochiai, Akiko. “The Port Royal Experiment Revisited: Northern Visions of Reconstruction and the Land Question.” New England Quarterly. Vol. 74 (2001), 94-117.