Collections Online

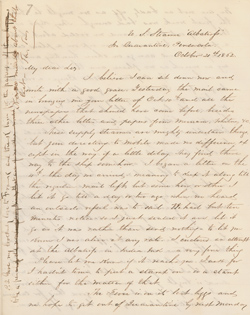

Letter from John Eliot Parkman to Eliza Shaw Parkman, 21 October 1862

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Civil War ]

While his ship, the USS Albatross, is in quarantine off the coast of Pensacola, Florida, John Eliot Parkman writes a serial letter, spanning from 21 to 30 October 1862, to his sister Elizabeth living in Boston. Writing with his trademark wit and humor, Parkman shows a range of emotions -- from homesickness to excitement to anger and frustration – as he describes the conditions aboard the ship, remarks on current events, and ruminates about what the future holds for the country.

John Eliot Parkman, known to his family as both Eliot and Jack, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1834, the youngest child of Unitarian minister Francis Parkman, Sr., and Caroline Hall Parkman. Among his many siblings were his better-known brother, historian Francis Parkman, Jr., and his sister Elizabeth, the recipient of this letter. As a young man, Eliot circumnavigated the globe several times aboard various mercantile vessels. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the crew of the USS Bainbridge as a captain’s clerk, a civilian position he held on various ships throughout the war.

In August 1862, Parkman transferred to the USS Albatross, to serve as a clerk to Captain Henry French. The Albatross was assigned to the western portion of the Gulf of Mexico, and was patrolling the mouth of the Rio Grande when yellow fever broke out among the men on the ship. In this letter he describes the lack of sanitation aboard the Albatross, noting that he and his fellow seamen had not been able to wash their clothes for over two months (page 3) and that the water the sailors drink is “bright yellow and sometimes red from iron rust” (page 2). Displaying his sharp and witty sense of humor, Parkman tells his sister that the water is “pretty to look at and a good thing for canaries when moulting but nasty as a beverage for man.”

Extolling his love for and pride in his native Boston, Parkman states “Old Boston is a perfect old trump, & the longer I live the more I glory in being born there” (page 4). He attributes this outburst to having read his sister’s account of “that Sunday work at Tremont Temple,” a reference to events that transpired on Sunday, 31 August 1862, when news reached Boston of the Union loss in the Second Battle of Bull Run. An estimated eighteen hundred women – the number given in an eye-witness account – gathered at Tremont Temple in Boston and spent the day sewing clothing and bandages for the surviving and wounded soldiers, while other citizens offered donations to fund the transportation of those goods to the front. Commenting on other current events, Parkman indicates his horror at accounts told to him by deserters and prisoners from the Confederate Army that the slave holders have become exceptionally cruel in the few weeks since President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam. He relates that slave holders have been known to shoot their slaves “down in their tracks” if the latter “as much as look queer” (page 4).

Parkman also relates his frustration with the state of the country, especially the soaring rate of inflation due to the now seemingly lengthy war ahead. He ruminates that “if our beloved country should continue to go to the devil at the rate it has been traveling for the last year, it will reach its destination quite soon enough” (page 6). Eliot then fantasizes about an alternative life after the war adding, “I move we quietly pack up our traps and move to some country that isn’t quite so free. Canada seems to offer inducements – with what it costs to live in Boston one might, I imagine hire the best house in Montreal and live like fighting cocks and Mother might slam round town behind her own horses too” (pages 6 & 7).

Once the Albatross was released from quarantine, Captain French was recalled, losing command of his ship for leaving the Rio Grande without permission when yellow fever struck. Parkman transferred to the USS Susquehanna, an “old fashioned side wheel steamers … with a crew of four or five hundred men’” to serve as clerk to Captain Robert Bradley Hitchcock. In the summer of 1863 he transferred to the USS Aries. In January 1864, Parkman and several of his mates from the Aries were captured by a Southern cavalry unit. After spending eight months as a Confederate prisoner he was released as part of a prisoner exchange. Upon his release, he joined the crew of the USS Brooklyn, where he remained until the end of the war.

Following the war, Parkman spent several years traveling in the Midwest, settling for a few years in Colorado. He later took a position as secretary to Commodore Roger N. Stembel, commander of the North Squadron of the Pacific Fleet. In December of 1871, while in San Francisco awaiting orders to sail, 37-year-old Parkman died from injuries sustained in a fall.

Sources for Further Reading

The featured letter is from the John Eliot Parkman Papers, a collection of about 350 letters written by John Eliot Parkman, primarily to his mother, Caroline, and his sister, Elizabeth. The MHS also holds a small collection of John Eliot Parkman Civil War Papers and additional material within the Francis Parkman Papers III. The latter contains a wonderful set of letters written while the younger Parkman was traveling in India in the mid-1850s.

Parkman, Francis. Letters of Francis Parkman. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960.

Underwood, Rodman L. Waters of Discord: The Union Blockade of Texas during the Civil War. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2003.