Collections Online

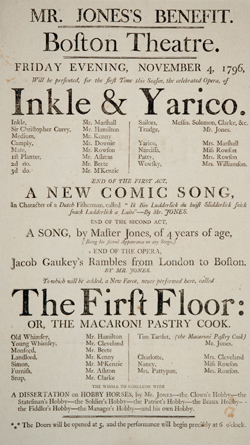

Mr. Jones’s Benefit. Boston Theatre. Friday Evening, November 4, 1796

To order an image, navigate to the full

display and click "request this image"

on the blue toolbar.

-

Choose an alternate description of this item written for these projects:

- Main description

[ This description is from the project: Object of the Month ]

This broadside announcing a benefit performance at the Federal Street Theatre in Boston on 4 November 1796 contains the name of the novelist, playwright, and actress, Susanna Haswell Rowson (here listed as “Mrs. Rowson”) in two supporting roles.

A danger to the souls of men—the controversial birth of public theater in Boston

Puritan Boston long looked with disapproval on theatrical productions as “a danger to the souls of men.” There were occasional attempts to stage plays in taverns and other public spaces during the colonial period, but they were strongly resisted. In 1750, the Massachusetts legislature passed An Act to Prevent Stage-Plays, and Other Theatrical Entertainment. In spite of the ban, illicit theatrical performances continued in Boston and, during the Revolution, officers of the besieged British garrison acted and performed in plays that they presented for their own entertainment and to satirize their self-righteous foes. Click here to view information about one such performance.

During the early national period, religious scruples combined with a residue of “anti-Britishness” (theatrical performances were seen as symbols of old world corruption) continued to stifle the development of a public theater in Boston, but a new generation of merchants and property owners, men and women who had come of age during the Revolution flouted the ban by opening an illegal theater in a “rough boarded hovel” in Board Alley. When Sheriff Jeremiah Allen attempted to close the theater during a performance of Sheridan’s School for Scandal on 5 December 1792, a riot ensued.

While public theatrical performances remained illegal, pro-theater forces in Boston pressed ahead. On behalf of his fellow stockholders, architect Charles Bulfinch designed an elegant 1,000-seat theater at the center of a town with a population of only about 20,000. On 3 February 1794, the Federal Street Theatre opened with performances of Gustavus Vasa and Modern Antiques or, the Merry Mourners.

The American Sappho: Susanna Haswell Rowson

The playbill for Edward Jones’s 4 November 1796 benefit lists “Mrs. Rowson” in supporting roles in both Inkle & Yarico, a comic opera by George Colman first performed in London in 1787, and James Cobb’s The First Floor: or, the Macaroni Pastry Cook, another imported English musical farce. Susanna Haswell Rowson (“Mrs. Rowson” in the playbill) had relatively minor, stock roles in both: as “Patty” in Inkle & Yarico, and as the easily-beguiled “Mrs. Pattypan” in The First Floor, but by 1796, Rowson already had several careers—and many adventures—behind her and, after a brief interlude at the Federal Street Theatre, she would soon set forth on another, as the proprietor of the first academy for young women in Boston.

Born in 1762 in Portsmouth, England, the daughter of an officer in the Royal Navy, Susanna Haswell was shipwrecked in Boston Harbor when she arrived there at the age of five. She settled with her family in Hull, a small coastal town south of Boston. During the Revolution, her father was imprisoned and the family went into exile in England after he was freed in a prisoner exchange in 1778. An impoverished refugee, Susanna began writing songs, poetry, theater criticism, and novels, including Charlotte: A Tale of Truth (1791) that, republished in America as Charlotte Temple (1797), would become early America’s best-selling novel. In 1786, she married William Rowson, a musician and actor who was never able to support his family, so “Mrs. Rowson” continued her literary career and became an actress. The couple toured the British Isles with a theater company and then emigrated, Susanna for a second time, to America in 1793. A versatile actress and dramatist (she wrote a topical musical entertainment about the Whiskey Rebellion, The Volunteers), Susanna Rowson had performed in Annapolis, Philadelphia, and Baltimore before coming to Boston to appear at the Federal Street Theatre in 1796. She had continued to write novels and plays; her Slaves in Algiers and Americans in England would be performed the following year at the Federal Street Theatre.

Women were born for universal sway; men to adore, be silent, and obey.

Few early American playwrights had any real success in breaking into the standard repertoire of British theater imports, but Susanna Rowson’s Slaves in Algiers kicked up a controversy when it was first performed in Philadelphia in 1794. The strong feminist statements delivered by Rowson’s characters: “a woman can face danger with as much spirit, and as little fear, as the bravest men among you,” and lines from the epilogue that she delivered herself from the stage, after acting in the play: “women were born for universal sway; men to adore, be silent, and obey,” provoked an immediate, scornful attack by William Cobbett, writing under the pseudonym of “Peter Porcupine.” In A Kick for a Bite; or Review upon Review; with a Critical Essay, on the Works of Mrs. S. Rowson (1795), Cobbett described her as “The American Sappho.” While more temperate commentators pointed out that Slaves in Algiers was a comedy, Rowson proved perfectly able to defend herself in print, referring to Cobbett as a “loathsome reptile” who had “crawled over” her writings.

For all of its early promise, the Federal Street Theatre was not a success, and it burnt to the ground in February 1798. While it arose phoenix-like and reopened later the same year, by then the Rowsons had moved on. Although Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple became extraordinarily popular when it was republished in the United States and, over time, Slaves in Algiers entered the American theatrical repertoire, Rowson embarked on yet another career. She opened a school for young ladies in Federal Street, in the shadow of the theater, from where it moved to neighboring towns before returning to fashionable Hollis Street in Boston. Rowson died in 1824, mourned by her students and much celebrated by the enormous readership of Charlotte Temple and her other eclectic writings.

A New Exhibition on the Federal Street Theatre

Further reading

Ball, William T. W. "The Old Federal Street Theatre." The Bostonian Society Publications. Vol. 8. Boston, 1911, 41-91.

Nathans, Heather S. Early American Theatre from the Revolution to Thomas Jefferson: into the Hands of the People. Cambridge: New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Parker, Patricia L. Susanna Rowson. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1986.

Rust, Marion. Prodigal Daughters: Susanna Rowson’s Early American Women. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Weil, Dorothy. In Defense of Women: Susanna Rowson (1762-1824). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976.