By Susan Martin, Collection Services

The Joseph H. Hayward family papersis one of five collections on deposit at the MHS from the Mary M. B. Wakefield Charitable Trust. The collection contains over two centuries of correspondence, diaries, sketchbooks, and other personal papers of members of the Hayward family of Milton, Mass., including Civil War surgeon John McLean Hayward (1837-1886).

John McLean Hayward, or “Mac,” graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1858. His family had already produced a number of doctors, including his father Joshua Henshaw Hayward, his uncle George Hayward, and his grandfather Lemuel Hayward. While still in his twenties, Mac was commissioned surgeon of the 12th Regiment of Massachusetts Infantry, otherwise known as the “Webster Regiment” after its first commander Col. Fletcher Webster. Mac served with distinction at Bull Run, Antietam, and other battles.

Unfortunately, on 19 November 1862, he was captured by the Confederate Army at Warrenton, Va. The Hayward collection contains some fascinating documents related to this incident, including the certificate of his parole, signed by Capt. Robert Randolph of the Black Horse Troop, 4th Virginia Cavalry. On the reverse of this document is a note granting Hayward passage “from Confederate into Federal lines.”

Hayward’s capture was complicated by the fact that he served as a non-combatant. General Order No. 60, issued on 6 June 1862 by the U.S. War Department, stated in no uncertain terms that medical personnel were off-limits. Paragraph 4 of the order read: “The principle being recognized that medical officers should not be held as prisoners of war it is hereby directed that all medical officers so held by the United States shall be immediately and unconditionally discharged.” On 26 June, the Confederate States of America did the same with its General Order No. 45.

On 26 November 1862, Hayward forwarded his parole to the assistant adjutant general in Washington, enclosed in a letter describing the circumstances of his capture. He explained that he had been ill for some time. When the 12th Regiment had decamped from Warrenton, he stayed behind to recuperate and was captured when Confederate troops marched into town. He wrote, “On the 19th Gen. Steward [Jeb Stuart] arrived and demanded my parole. I at first refused to give it on the ground that I was a surgeon and could not be paroled, but Steward took the ground that as I was not in charge of any sick at Warrenton I should be treated like any other officer in the same circumstance and if I refused my parole I should go a prisoner to Richmond.”

Annotations on the back of Hayward’s letter show a series of referrals. In just three days, the letter made its way to the Commissary-General of Prisoners Col. William Hoffman, then to Lt. Col. William H. Ludlow at Fort Monroe, Agent for Exchange of Prisoners. In his referral to Ludlow, Hoffman wrote, “This case comes clearly under Order No. 60, June 6th par. 4 – and Dr. Hayward should be released.” Ludlow agreed, writing, “The parole given by Dr. Hayward is null and void.”

Hayward eventually returned to his regiment, but had to resign his commission in April 1863 due to poor health. After serving for a short time as post surgeon at the Long Island conscript camp in Boston Harbor, he opened a private practice in Boston. In an interesting postscript to his Civil War service, documents in the collection indicate that, on 26 March 1864, he exhibited an invention to the Suffolk District Medical Society – a “mule ambulance” of his own design. The society immediately approved his invention for submission to the War Department.

John McLean Hayward was clearly well-respected as a doctor and a military man. His friend Col. James L. Bates, speaking on behalf of the regiment in a letter to the surgeon general, described Hayward as “a gentleman whom we all love and esteem, and in whose skill in surgery and medicine we have an unbounded faith.”

To learn more about the Hayward family, please visit the MHS library.

to tell portions of the story. MHS materials feature prominently in two segments of the film. In the segment “Dying” a letter written by Wilder Dwight to his mother Elizabeth Dwight (

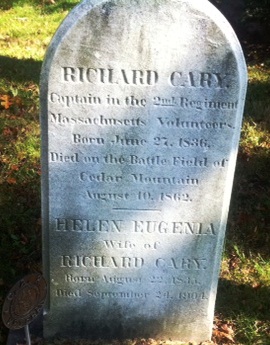

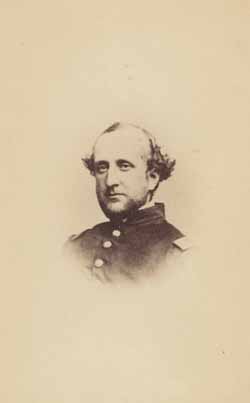

to tell portions of the story. MHS materials feature prominently in two segments of the film. In the segment “Dying” a letter written by Wilder Dwight to his mother Elizabeth Dwight ( Captain Richard Cary of the Second Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the subject of the

Captain Richard Cary of the Second Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the subject of the