By Amanda A. Mathews, Adams Papers

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.

We do know, however, what John Quincy Adams’s son Charles Francis Adams, minister to Great Britain during the Civil War, thought of President Lincoln. “Mr Lincoln is a tall, illformed man,” Adams wrote in his diary after their first meeting in February 1861, “with little grace of manner or polish of appearance, but with a plain, goodnatured, frank expression which rather attracts one to him.” Adams, part of the Boston elite, had little respect for his ability as a social host or leader. Shaking hands with Lincoln at his inauguration ball on March 4, Lincoln appeared to have forgotten him. “Were it any body but a Western man I should have construed it as an intentional slight,” Adams wrote.

illformed man,” Adams wrote in his diary after their first meeting in February 1861, “with little grace of manner or polish of appearance, but with a plain, goodnatured, frank expression which rather attracts one to him.” Adams, part of the Boston elite, had little respect for his ability as a social host or leader. Shaking hands with Lincoln at his inauguration ball on March 4, Lincoln appeared to have forgotten him. “Were it any body but a Western man I should have construed it as an intentional slight,” Adams wrote.

Lincoln’s handling of the Civil War only partially softened Adams’s impression. “Mr Lincoln has certainly in some respects acquitted himself with honor,” Adams wrote on  March 30, 1865, “But nothing could ever make him a gentleman, or a sagacious administrator in the selection of agents.”

March 30, 1865, “But nothing could ever make him a gentleman, or a sagacious administrator in the selection of agents.”

Upon hearing of Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Adams’s final assessment is in true Adams style, accurately recognizing Lincoln’s larger place in history as well as the questions left unanswered:

To the country, the loss of Lincoln is hardly reparable. There was a grandeur about the national movement under his direction which even he might not have been able fully to sustain, but which his successor will not attempt to continue. For his own fame, the President could not have selected a more happy close. The just doubts about his capacity for reconstruction are scattered to the winds in the solemnity of the termination. From that moment his fame becomes like that of Washington the priceless treasure of the Nation.

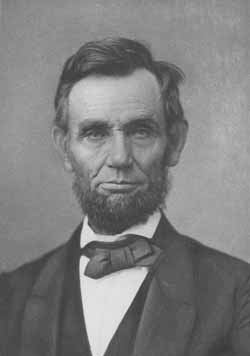

Images: Top, John Quincy Adams (17 -1848), carte de visite of daguerrotype (1847) by Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries, [Matthew B. Brady], after 1860; Middle, Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), photomechanical, from Portraits of American Abolitionists, MHS photograph #81.410; Bottom, Charles Francis Adams (1807-1886), photogravure, from Portraits of American Abolitionists, MHS photograph #81.2

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.

Recent viewers of Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln may be wondering whether an Adams-Lincoln connection exists as the Adamses always seem connected to the major figures of American history. John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln indeed served together in the 30th Congress for three months before John Quincy Adams died on February 23, 1848. Lincoln served on the Committee of Arrangements for Adams’s funeral, but that is the only conclusive connection between the two. They shared similar political outlooks, particularly on slavery, but what Adams thought about the young Lincoln, history does not record.