By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

Feb. 2d, 1864

The President has just ordered out 500,000 men.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

The President has just ordered out 500,000 men.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

In regard to public events, the year has witnessed many calamities, through the rage of civil war; but God has sustained us, and it now seems as if the end, – and a righteous and permanent end, – was nigh. May He grant its speedy attainment!

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

The life of a Civil War soldier was difficult even at the best of times, but holidays were particularly poignant. Many of the men were very young and away from home for the first time. Edward J. Bartlett of Concord, Mass. had been just 20 years old when he enlisted in August 1862. In his letters home in November of that year, written from New Bern, N.C., he described his first Thanksgiving as a soldier, the elaborate preparations, the decorations, and especially the food:

First we had oysters then turkey and chicken pie then plum pudding then apple raisin & coffee with plenty of good soft bread & butter. After we had all eaten a little too much, people usualy do on Thanksgiving days and we who had lived so long on hard tack did our best[,] we had a fine sing.

The meal was followed by songs (including “Auld Lang Syne”), speeches, toasts to President Lincoln and the troops, games, and a dance. Deep in hostile territory, the men were determined to celebrate “in the true home style.” Bartlett concluded that:

The whole day was very succesfull every thing went of[f] pleasently, not a thing went wrong. We were surprised that such a dinner could be got up in this God forsacken country. Twas pleasent to celebrate Thanksgiving in such a way.

The next year, his letters were more sober. Writing on 15 November 1863 from Nashville, Tenn., Bartlett reflected:

Our company Thansgiving in the barracks last year is a day that I can never forget. Six of those boys are now dead. Poor Hopkinson, the president, in his address, [said] “that he hoped the next year would see us all at our own family tables.” He died two months after.

Bartlett spent Thanksgiving 1864 stationed at Point Lookout, Md., guarding Confederate prisoners-of-war. He wrote to his sister Martha about his homesickness on the evening before the holiday:

Thankgiving eve. I sat over the fire, thinking of what you were doing at home, and what I had done on all the Thanksgiving eve’s, that I could remember.

The day itself, however, proved to be a rousing celebration that included music and dancing (“It was fun to see them kick thier heels about.”), horse races, sack races (“Such a roar of laughter I never heard before. Most of them were flat in the dirt before they had gone three steps.”), wheelbarrow races, a turkey shoot, greased-pole climbing, and greased-pig chases (“This made more sport than all the rest put together.”). Bartlett again, unsurprisingly, lingered over his description of the meal: oysters, turkey, duck, beef, chicken, vegetables, apple pie, pumpkin pie, mince pie, etc., finished off with cigars.

Edward J. Bartlett survived the Civil War and lived to 1914. To learn more about Bartlett, visit our Civil War Monthly Document feature for November 1863 or visit the MHS Library to read more of the papers in his collection.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

Of military affairs, the rumor is now, – said to be confirmed to-day, – of the taking of Fort Sumter by our forces. We hear of late sad accounts of the treatment of Union prisoners by the rebels, – their suffering from want of food, etc. Their own destitution may partly extenuate this wrong. God grant the end be soon, & the victory of Union & freedom!

The rumor mentioned in my last entry [the recapturing of Fort Sumter] was not corroborated; but successive advantages give good hope for the cause of Union and Freedom. We lament meanwhile, for the sufferings of our brave men, prisoners in Richmond, said to be almost starved. A plot has been revealed through the British authorities, formed by refugees in Canada, for attacks on our lake cities etc.

Last week occurred the Dedication of the Battle Cemetery at Gettysburg. An oration by Mr. Everett, & some noble words from President Lincoln.

Of public events, I must name with solemn gratitude the victory granted to the union arms near Chattanooga & Lookout Mountain. Hope is again encouraged that the end of this awful strife is near.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

Sunday Oct. 4th, 1863

“Of public news, the battle near Chattanooga, & in which my relative Major Sidney Coolidge, and my friend S. Hall’s son Henry were wounded, – The favorable news from England, – and the arrival of a Russian fleet at New York, where it is warmly welcomed, are the chief items. The first is unfavorable, but on the whole, our country’s cause seems advancing, thanks be to God!”

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

I have received to-day a very pleasant letter from Maria….She writes pleasant intelligence also, of my brother-in-law and former assistant, George A. Howard. He is now in beleaguered Charleston, but the seriousness of the time, or some other cause, seems to have made a very happy change in him. His nephew and mine, my godson, Cyrus Bulfinch Carter, is in the Confed service, & has been stationed at Fort Wagner, at Charleston.

With a sigh for all the miseries of this time, – of which, as of its crimes, a most awful example is given by the recent massacre of Lawrence, Kansas, – I yet rejoice at the increasing success of the Union Arms – God grant his keeping for the restoration of peace, & the progress of freedom!

Today I went in to preach at King’s Chapel but did not, owing to some mistake. Heard a good sermon from Mr. Foote, referring touchingly to the losses by the war, – particularly the cares of Major Paul Revere and Mr. Perkins, the death of the latter having been only learned of yesterday.

The war continues with varied success in individual encounters, but important gain on the whole, to the cause of Union and Freedom. The eyes of public expectation are now fixed on Charleston, – Northwestern Georgia, – the Texas expedition, – and the Rappahannock. There is anxiety about our foreign relations, but we can hardly think English statesmen will be guilty of so great a crime and folly as to force us into a war. God grant that way be spared us! Mr. Sumner’s speech, recently delivered, must, one would think, make them feel the unworthiness of their position. The danger from France seems to be passing away.

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

Unfortunately we’ve come to our last installment on the letters of Moses Hill here at the MHS. After the devastating fighting around Richmond that I described in my previous post, Robert E. Lee drove the Union army south to Berkeley Plantation on the shores of the James River. This estate served as George B. McClellan’s headquarters in July and August 1862, and here Moses and the other Andrew Sharpshooters got a short respite, a chance to regroup while the Union forces were replenished with new recruits.

Over the last two weeks, Moses had fought in multiple battles, including Savage’s Station on June 29, Glendale on June 30, and Malvern Hill on July 1. He wrote to his wife Eliza about the grueling retreat:

I think there must of been a great meny sick & wonded left behind. After I gave out I saw hundreds of wonded & sick limping and working themselvs along the best way they could. It was a horable sight to see them exert every nurve and strife for life. I am glad you did not see them. Horses would run over them and nock them down. They had to creep crall any way to get along.

Union morale was low after the failure to take Richmond, but Moses still hoped to be back home in Medway, Mass. soon. He treasured a photograph Eliza had sent him:

I received your Picture and I think it looks very naturel or as you looked when I left home. I think I shold remember how you all looked if I was off for a long while. I like to take your picture out and look at it. I think of you a great deal and the children too.

However, Moses had been complaining more frequently of illness, and he finally confessed to his wife, “I have been quite unwell long back.” He suffered from diarrhea and fatigue, weighed only 126 pounds, and was sometimes too weak to walk even a half-mile. His clothes were in tatters, and he was plagued by the heat and the flies. His mother, Persis Hill, described one of his letters as “the most disenharted letter he ever has rote. It seames he is all down and discouraged.”

On 16 Aug. 1862, the Union troops decamped from Berkeley Plantation and moved downriver to Newport News. Moses wrote to his family from there a week later. But while he had been a regular correspondent during his year of military service, they wouldn’t hear from him again for almost a month. On September 18, he wrote from Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C.:

It is a very pleasant place but it is not home….Eliza I should of writen before but I have been so unwell that I did [not] feel as I could. I think I have wored about you as much as you have about me, for I knew that you did not know what had be[c]ome of me. I am run down and I want a good nursing. I ought to be at home. Some days I am better and then I am worse, but If I take good care of myself I think I shall get a little stronger….Dear Eliza do not worry about me for I shal try to getalong. I will write again soon. You must excuse me for I am very tired. My love to all and lots of kisses.

This is the last letter in the collection written by Moses Hill.

His family received his letter “with the greatest pleasure imaginable.” Eliza was relieved he had been spared from the battle at Antietam, where his regiment suffered terrible losses. (She added guiltily, “I know it is selfish to say so, but I cannot help it.”) She and their teenaged daughter Lucina wrote to Moses several times at the hospital, but did not receive any replies. Their letters became more and more frantic. On October 5, Eliza wrote:

I feel very anxious about you. If you are not able to write yourself, do get some one to write for you. Mother Hill and your sisters are as worried as I am. We want to know just how you are, what ails you. I want to have you come home for me to take care off, if it is possible….I think of you, and pray for you, daily, and hourly….I want to see [you] so much. I send you my best love, and wishes, with many kisses.

Lucina added a postscript about her three-year-old brother: “Georgie askes for father about every day.”

With the help of George Lovell Richardson of East Medway, Moses Hill was discharged from service on 13 Oct. 1862. Richardson accompanied him home, and they reached Medway on the 17th. Moses died of consumption 12 days later. He is buried at Prospect Hill Cemetery in Millis, Mass.

Eliza Hill died in 1888.

Left to right: Lucina (Hill) Howe, Helen Richardson, Eliza Hill, and Genieve Richardson

Left to right: Lucina (Hill) Howe, Helen Richardson, Eliza Hill, and Genieve Richardson

Undated photograph, circa 1885. Frank Irving Howe, Jr. Family Papers.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

Have sympathized with the relatives of Henry Foster, who died by his own rash or bewildered act, at New Orleans, and of my friend Rev. T. B. Fox’s son, who received a mortal wound at Gettysburg.

Monday, we had the pleasure of welcoming home our young neighbors, C. & D. Weymouth, who arrived with their regiment, the 42d. They have been prisoners in Texas, and since then in a paroled camp near New Orleans…Today, the village (Bridgewater) is lively with the mustering-out & paying off, of three companies of the returned Third Regiment.

By Susan Martin, Collection Services

Welcome back to our series on the letters of Moses Hill, part of the Frank Irving Howe, Jr. family papers here at the MHS. In my last post, I described Moses’ experiences during the Siege of Yorktown as part of McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. After the siege, Rebel forces retreated to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, with the Union army hard on their heels. Moses’ regiment, the 1st Massachusetts Sharpshooters, had been attached to the 15th Regiment Massachusetts Infantry, Sedgwick’s Division, since April 1862. They traveled up the York River to West Point, arriving in the midst of the fighting there, then continued west through New Kent toward Richmond.

Some of my favorite letters in the collection were written during this time. Moses was especially reflective and honest after nearly a year of hard service. On 26 May 1862, he wrote to his mother Persis (Phipps) Hill:

Some times it looks rather dark and as if the war might last for some time yet, and some times It looks as if it might close soon. I supose you have seen all my letters that I have sent Eliza so I will not write meny poticulers but I can say I have seen some hard times….I am sick of fighting and shooting our Brother man.

…Dear Mother I do not see such times as I use to when I could go to the old cupboard and eat of your cooking and eat my fill of boild vitils and custard pie and every thing that was good. I cannot have that now….I hope I shal live to come home and eat one good meal with you. How I would enjoy it.

…Love to all, From your never forgetful Son Moses Hill

While Moses approached Richmond, two of his sister’s sons, John and Albert Fales, were serving under Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks in the 2nd Regiment Massachusetts Infantry, Company E, and currently fighting Stonewall Jackson’s troops in the Shenandoah Valley. Moses worried about his nephews in his usual understated way:

They dont know what fighting is and I hope the[y] never will. I have seen enough of it and I hope I shal not see any more….It is not very agreeable.

Unfortunately, just days later, Moses would take part in the worst battle he had seen yet. The Battle of Seven Pines, otherwise known as the Battle of Fair Oaks, was fought from 31 May-1 June 1862 on the outskirts of Richmond. Moses described it to his wife Eliza in gruesome day-to-day detail:

The Surgents [surgeons] was cutting of[f] legs and armes, and dressing wounds all night. The grones was terible. I did not sleep that night. [31 May]

…The dead and wonded lay one top of another when the Battle was through. The ded lay on all sides of us where they was kiled the day before. Along the fences they lay some with their faces up, and some with their fases down and in all shapes. It was a horable sight. [1 June]

…The dead was about all buared today. Our armey did not bring meny shovels with them so it took some time….There was one on each side of where I slep that lay dead with in a few feet of me. They s[c]ented very bad. The magets was on them, but they burried them as fast as they could. [2 June]

…If you see any body that complains of hardship tell them to come into this armey and they will begin to find out what it is.

Even in the darkest times, however, Moses never seemed to lose sight of the humanity of his enemy. He wrote about the Confederate soldiers captured by the Union army:

They Belonged to Georgia Alabamma North Carlonia. I went and talked with them. They said they wanted to get home. The ground was so wet that it was very uncomftible for them. I pitied them from the Bottom of my heart. The ground was most all coverd with water. One of them asked me for my pipe and I gave it to him to smoke.

McClellan failed to take the city of Richmond and was driven back by Robert E. Lee in the Seven Days Battles. Stay tuned to the Beehive for more!

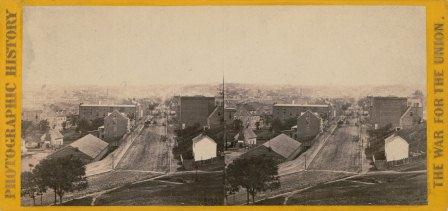

**Image: “War Views. Panoramic View of Richmond, Va. From Libby Hill, looking west.” Published by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co. (New York, N.Y.). Original photographer unknown. From Adams-Thoron Photographs, MHS.

By Elaine Grublin

The following excerpt is from the diary of Stephen Greenleaf Bulfinch.

4th. The great anniversary, rendered still more famous now, was very quietly spent here. At ½ past 1, I went into Boson, & at the depot bought a paper, containing the announcement by the President of the successful issue so far of the three days’ fight at Gettysburg, – which I read with thankfulness & hope.

The great theme of conversation has been the riots in New York & Boston, occasioned by the Conscription. Blood shed in both. Law triumphant here, and I trust also there.

Meantime, thanks to God for victory at Port Hudson, – near Vicksburg, – in Arkansas, – and some success near Charleston.