By Katherine Dannehl, Reader Services

Gallipolis, Ohio is a village of 3,462 people nestled on the banks of the Ohio River. It has a few claims to fame, including being the birthplace of artist Jenny Holzer and hometown of Bob Evans of “Bob Evans” restaurants. Unrelated to conceptual art or country-themed restaurants, the town also played a major role in the American Civil War as the site of an extensive U.S. Army General Hospital for Civil War soldiers.

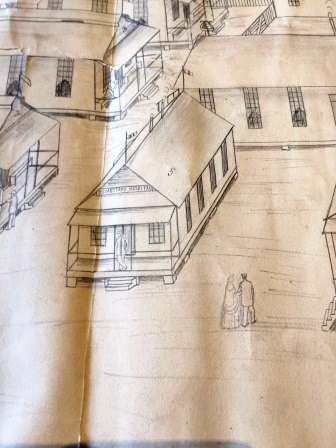

From the society’s collections: a hand-drawn map of the hospital, which stood from April 1862 until July 1865

The (unknown) artist drew detailed representations of the multi-building hospital, numbering and labeling each structure at the bottom of the map.

“Numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 are hospital ward buildings.”

The first four buildings are the dedicated hospital wards for the sick and injured. Building 5 is the two-in-one office and dispensary. The surgeon’s quarters and staff quarters are buildings 6 and 7, respectively. A dining hall and kitchen, house for the dead, bakery, laundry and linen room, stable, carpenter’s shop, and coal house round out the number of buildings at 14.

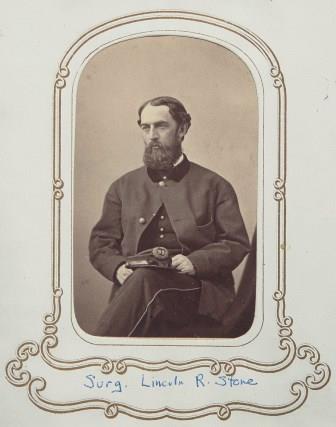

The hospital map is officially titled in our online catalog, ABIGAIL, as “Plan of U. S. A. Hospital at Gallipolis, Ohio, where Dr. and Mrs. Lincoln R. Stone spent the first seventeen months of their married life.” A military hospital doesn’t sound like an ideal place to honeymoon, but Dr. Lincoln R. Stone of Newton, Massachusetts was called to action to become the head surgeon of the hospital at Gallipolis immediately after his wedding in February 1864. He would reside there until the hospital’s closure in July 1865.

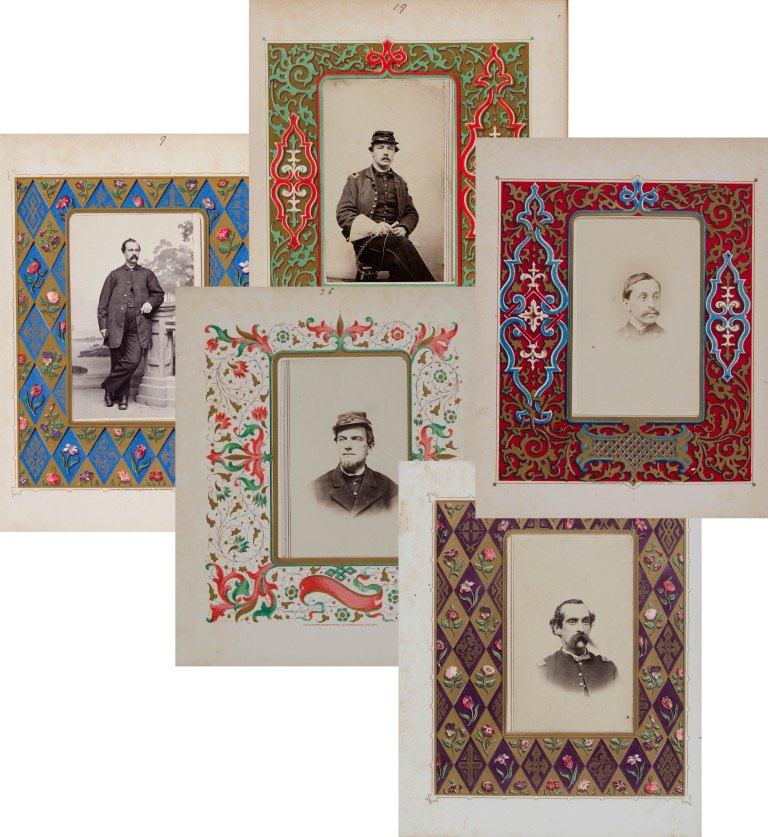

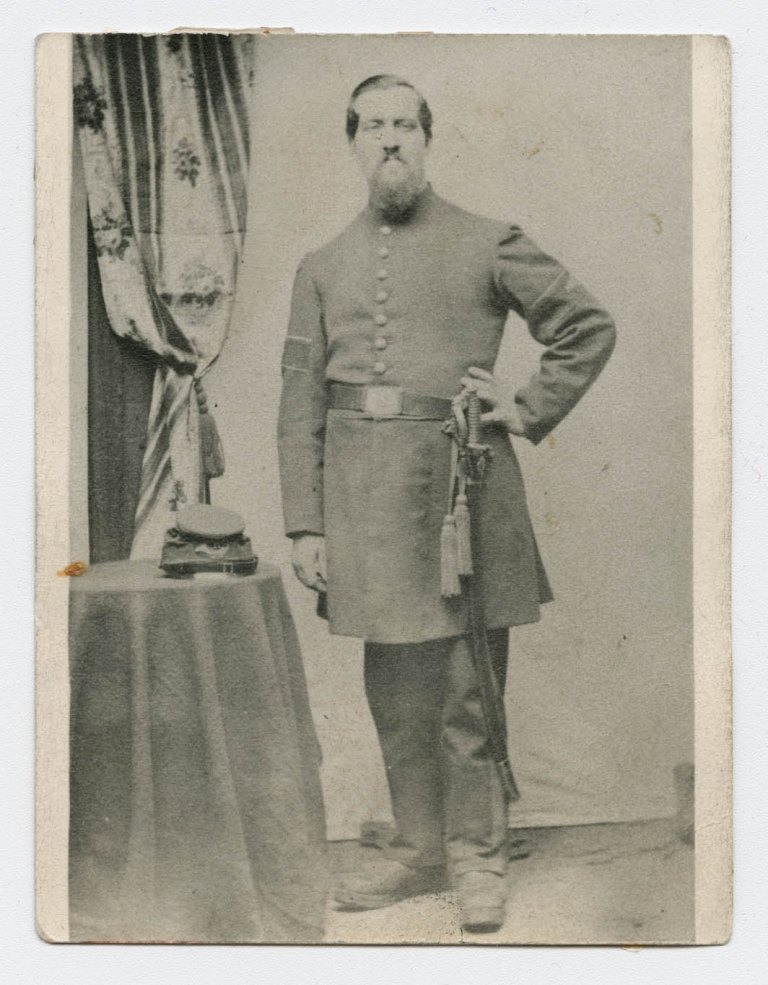

From the National Museum of African American History and Culture

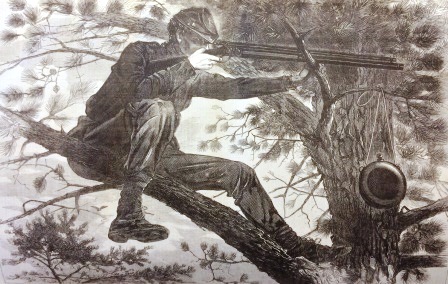

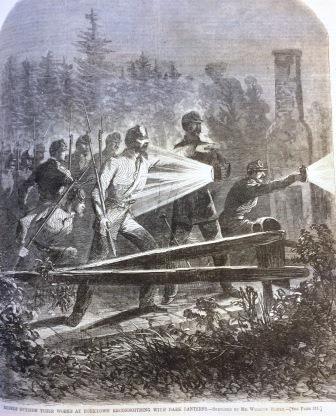

A native of Maine, Dr. Stone graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1854 and worked at Massachusetts General Hospital for a year before opening his own medical practice. In 1861, duty called him to serve as assistant surgeon to the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. At Winchester, Virginia, Stone was taken prisoner after refusing to abandon the hospital in his charge. He survived this ordeal and continued his military service, transferring to the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment upon the direct invitation of his close friend Robert Gould Shaw.

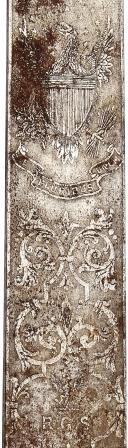

Robert Gould Shaw’s name has been buzzing through the halls of the society following our recent acquisition of the sword he wielded at Fort Wagner just before his death. Due to Dr. Stone’s consistently shifting posts at military hospitals, Dr. Stone would come to learn of Shaw’s death secondhand.

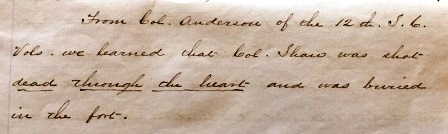

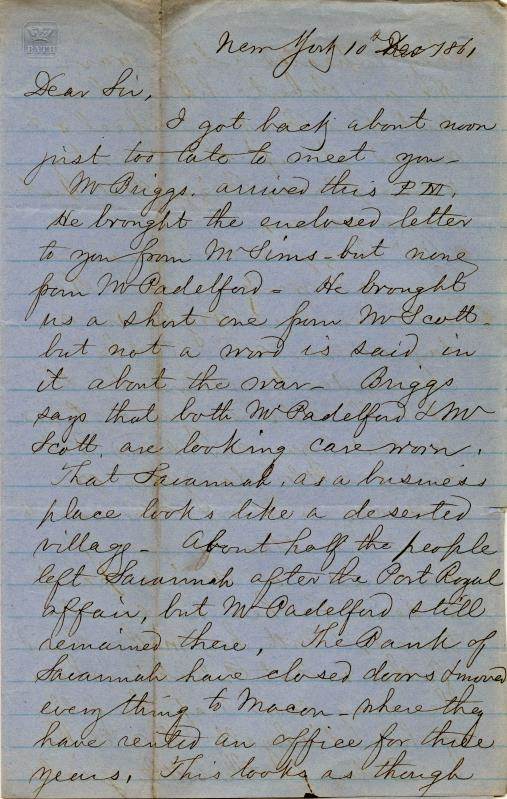

“…we learned that Col. Shaw was shot dead through the heart and was buried in the fort.”

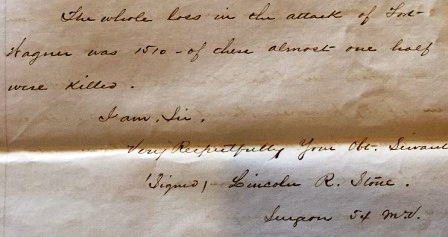

In this copy of a letter from our archives, which was sent to Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, Dr. Stone himself informs the governor of Shaw’s passing and of the total loss experienced at the battle.

“The whole loss in the attack of Fort Wagner was 1,510 – of these almost one half were killed.”

About seven months after the Fort Wagner attack, Stone married Ms. Harriet Hodges of Salem, Massachusetts and moved to Gallipolis to assume his post as resident surgeon. On October 1st, 1865, to honor his service, Stone was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Subsequently, he was mustered out on October 13th, 1865, and would return home to Newton to continue practicing medicine.

His wife Harriet Hodges Stone would become well-known to the community 30 years later as the founder of the Newton branch of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women.

Dr. Stone would come to live well into his nineties. He is buried at Harmony Grove Cemetery in Salem, Massachusetts with his family.

To view these featured American Civil War materials in person, consider visiting the library at MHS. If you get here sometime this summer, you can view Robert Gould Shaw’s sword while you’re at it!

You can also find additional information about the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women within our collections, though you will find those specific to the Newton branch and Harriet Hodges Stone at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

In Gallipolis you can visit the historical marker where the U.S. Army General Hospital once stood, on the corner of Ohio and Buckeye Avenues.

*****

Sources and Related Materials:

Marquis, Albert Nelson, ed. Who’s who in New England: A biographical dictionary of leading living men and women of the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Chicago: A.N. Marquis & Company, 1916. https://books.google.com/books?id=RmUTAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

“12-27 U.S. Army General Hospital,” Remarkable Ohio, accessed July 29, 2017, http://www.remarkableohio.org/index.php?/category/435

Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women. Newton Branch Committee. Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women Newton Branch Committee records, 1894-1902. http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/deepLink?_collection=oasis&uniqueId=hou02149

United States. Army. General Hospital, Gallipolis, Ohio. Army General Hospital of Gallipolis, Ohio: Correspondence, orders, rules, and regulations. 1864-1865. Located in: Modern Manuscripts Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD; MS C 24. https://oculus.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/f/findaid/findaid-idx?c=nlmfindaid;idno=army024

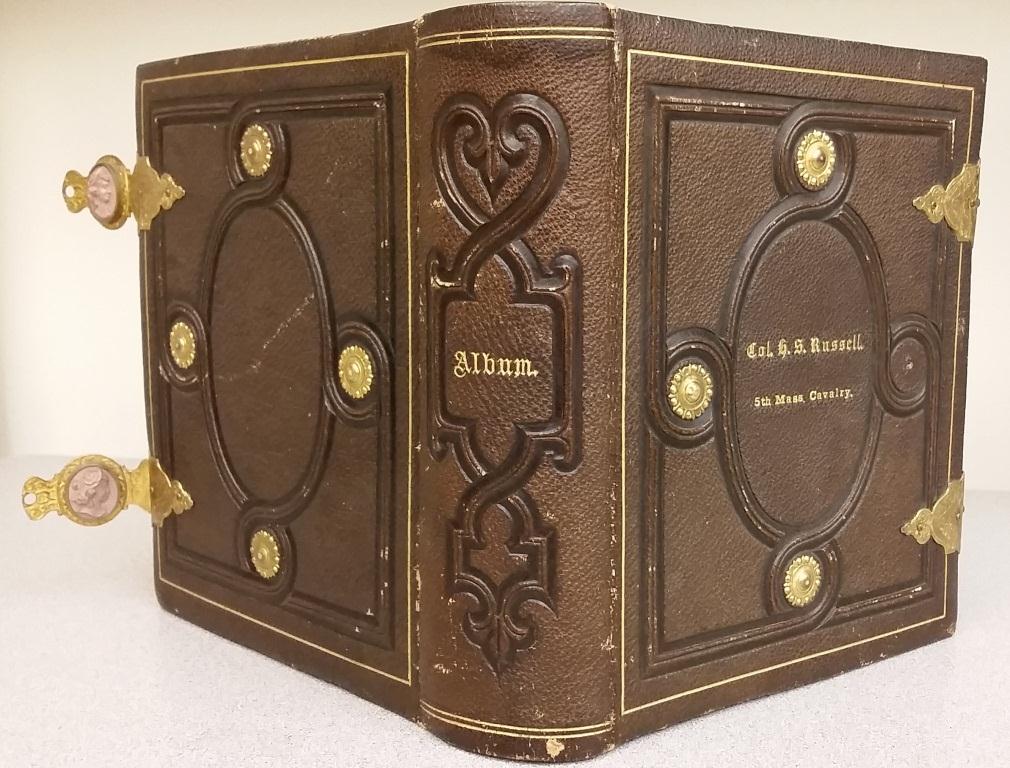

“Carte-de-visite album of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment,” National Museum of African American History and Culture, accessed July 28, 2017, https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2014.115.8#

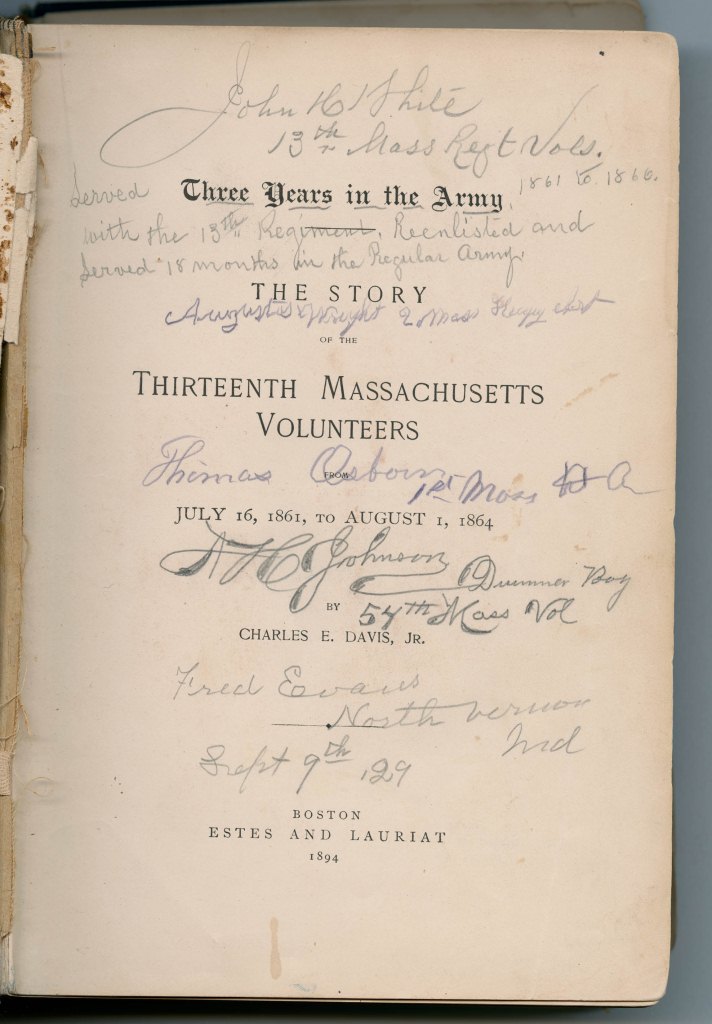

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments