Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

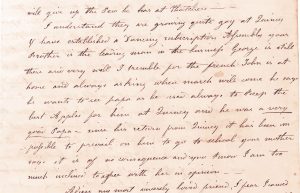

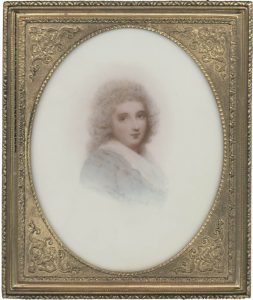

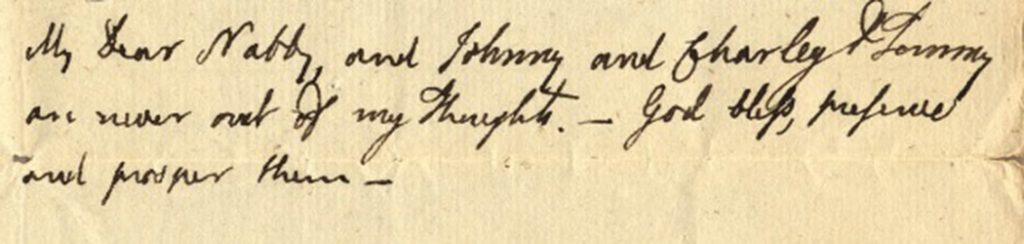

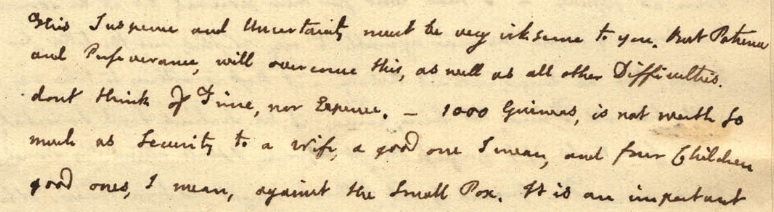

“You know I have always been a true friend to Matrimony,” Abigail Adams wrote to her friend Hannah Phillips Cushing on 1 Sept. 1804. “Upon this principle I last week parted with my most beloved domestic who was to me as a child in sickness and in Health and who had lived 14 years with me.” Abigail was referring to the Adamses’ servant Rebeckah Tirrell who married another longtime servant, Richard Dexter, at Peacefield on 23 August.

Here is where the letter gets interesting. “At the Wedding,” Abigail continued, “amongst other Guests were six couple who had lived with me during her residence with me all of whom had been married from me in that period & all but one married in my family. this I believe is rather a singular instance.”

Besides the bride and groom, the five other couples were Esther Field and John Briesler Sr. (m. 1788), Polly Doble Howard and Jonathan Baxter Jr. (m. 1797), Abigail Hunt and Ebenezer Harmon (m. 1798), Betsy Howard and William Shipley (m. 1801), and Elizabeth Epps and Tilly Whitcomb (m. 1802).

As if this occurrence didn’t have enough Upstairs, Downstairs flavor, Abigail’s letters prove that drama sometimes preceded the marital bliss. The first couple produced by the Adams household—Esther Field and John Briesler Sr.—probably caused Abigail the most grief. Field and Briesler had accompanied John and Abigail Adams to London during John’s time at the Court of St. James. They were married on 15 February 1788 at St. Marylebone church in London. Their daughter was born in May.

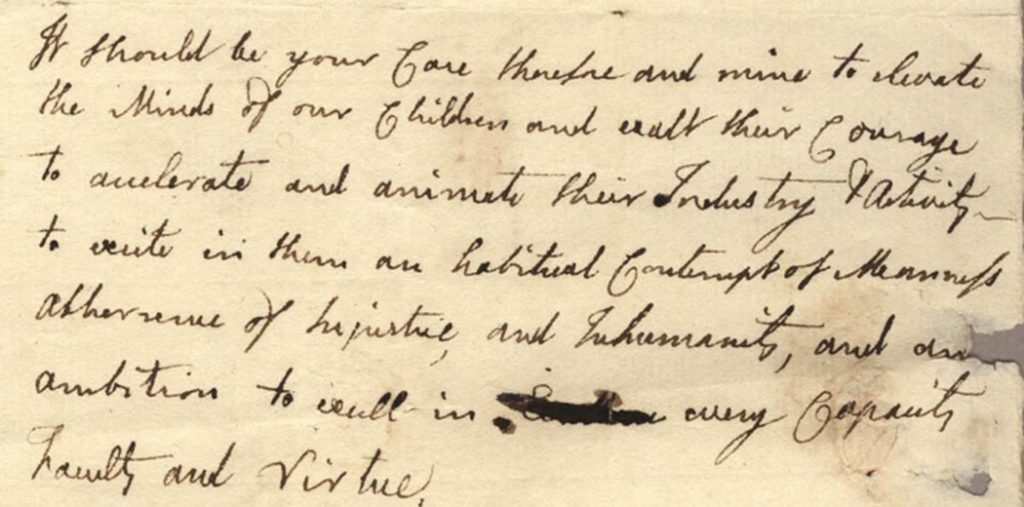

A frazzled Abigail confided to her sister, “I have the greatest anxiety upon Esthers account, if I bring her Home alive I bring her Home a marri’d woman.” Abigail stressed that no one outside of the family knew Esther’s situation. “I have related this to you in confidence that you may send for her Mother & let her know her situation. . . . in addition to every thing else, I have to prepare for her what is necessary for her situation.” Abigail wrote that Esther “came in the utmost distress to beg me to forgive her” and added that John Briesler, “as good a servant as ever Bore the Name,” was “so humble and is so attentive, so faithfull & so trust worthy, that I am willing to do all I can for them.”

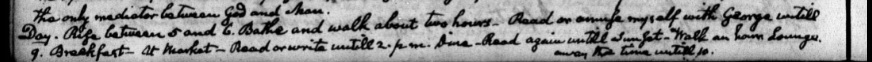

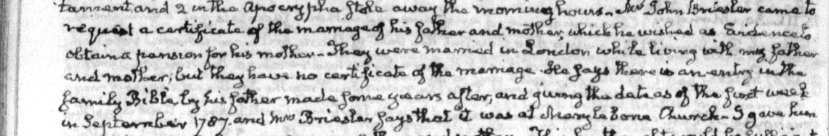

Doing all they could included going along with a vanished marriage certificate and a revised wedding date of September 1787, according to John Quincy’s 14 Aug. 1838 diary entry.

Abigail was willing to get involved even when propriety was not on the line. Her servant Polly Doble Howard was engaged to her sons’ servant, Tilly Whitcomb. When Whitcomb accompanied John Quincy and Thomas Boylston to Europe, Abigail passed along messages for the lovebirds. “Polly requests me to give information for her that Ten long weeks she has been constant.” (No error here. Howard was indeed engaged to Whitcomb before they broke off the engagement and she married Jonathan Baxter Jr. in June 1797. Whitcomb would marry Adams servant Elizabeth Epps five years later.)

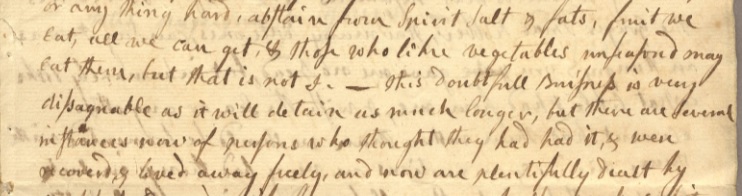

Even in the midst of her time as First Lady, Abigail hosted weddings for her servants. To her nephew William Smith Shaw, she wrote a familiar phrase: “I am a great friend to Matrimony, and always like to promote it, where there is a prospect of happiness & comfort.” After Ebenezer Harmon and Abigail Hunt were pronounced man and wife, Abigail “regaled them with a Glass of wine, & some cake and Cheese.” Abigail went to bed while the guests were still dancing “with the pleasurable reflection of having made Several honest families happy & pleasd.”

Perhaps it was the daily example of America’s first power couple that made the idea of marriage attractive to so many of the Adamses’ servants. Whatever the cause, Abigail reflected, “My Muster role would have been double if I had taken in all those Who had married with & from me Since I became a housekeeper.”

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. The Florence Gould Foundation and a number of private donors also contribute critical support. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press.