by Gwen Fries, Production Editor, Adams Papers

I don’t imagine you’ll be too bowled over when I tell you that I believe the Adamses’ writings have great value. There’s a reason that a team of us dedicate our lives to making their words and ideas accessible to all. (Have I mentioned our free digital edition?) While we give them hours of every day, our closest attention—and possibly our eyesight years before it would’ve failed otherwise—I don’t think we can ever repay all the wisdom, adventure, and laughter they give us. Frankly, they’re the best company for which you could ever wish.

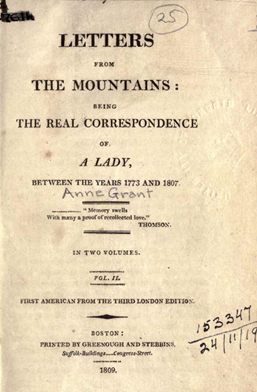

So, when a member of the Adams family writes about something they read that gave them the same kind of rush, my ears prick up. Thus was born my idea of Adams Book Club, where we find free and accessible works and read them to gain a deeper understanding of the Adamses and what make them tick. First up? Anne MacVicar Grant’s Letters from the Mountains.

“Pray have you met with these Letters from the Mountains?” Abigail Adams wrote to her daughter Abigail Adams Smith (Nabby) on 13 May 1809. “If you have not, I will certainly send them to you.” The “Mountains” in question are the Scottish Highlands. If you’ve been following along at home, you know Abigail had a particular affinity for all things Scottish. (Am I saying Abigail would’ve been an Outlander fan?…I’m not not saying that.)

“I have never met with any letters half so interesting,” Abigail gushed to her daughter. “Her style is easy and natural, it flows from the heart and reaches the heart. In the early part of her life, and before she met with severe trials and afflictions, her letters are full of vivacity, blended with sentiment and erudition. Though secluded from the gay world, she appears well acquainted with life and manners. Her principles, her morals, her religion, are of the purest kind.”

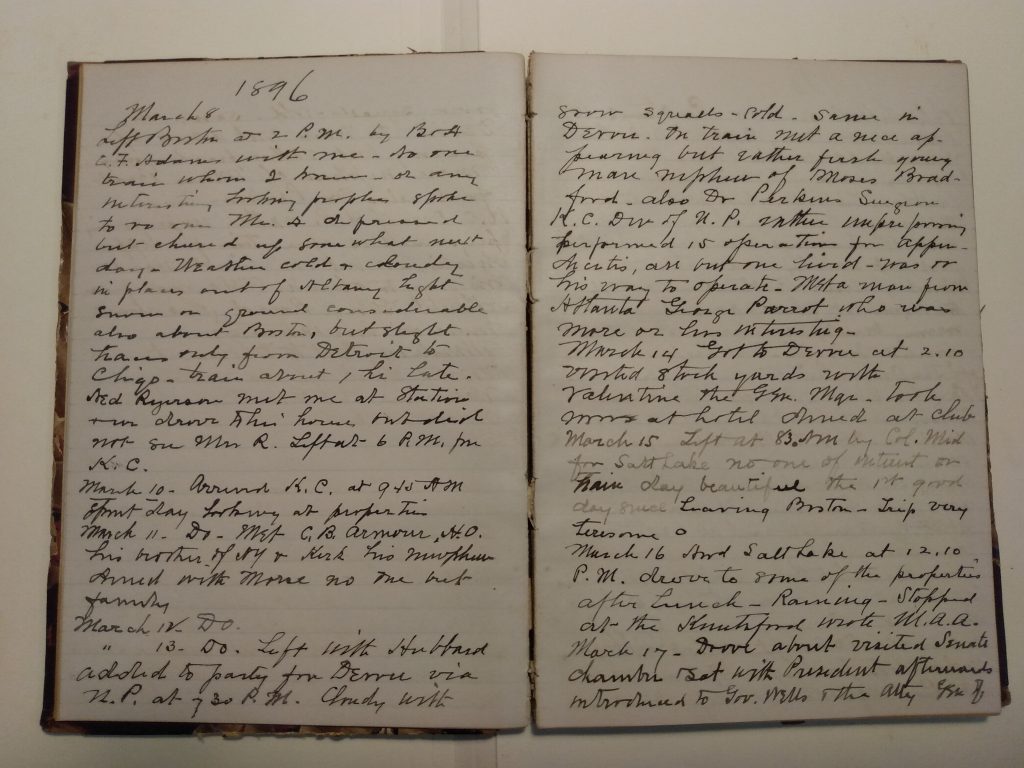

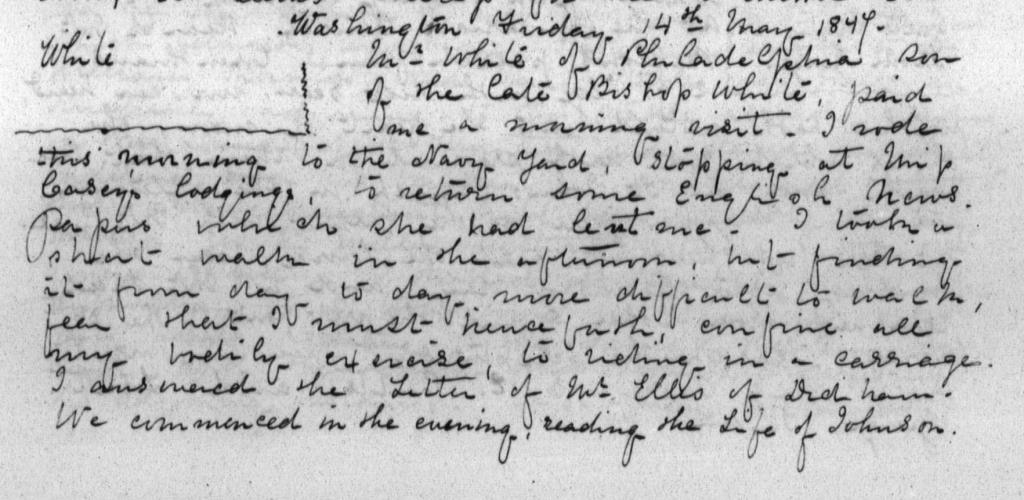

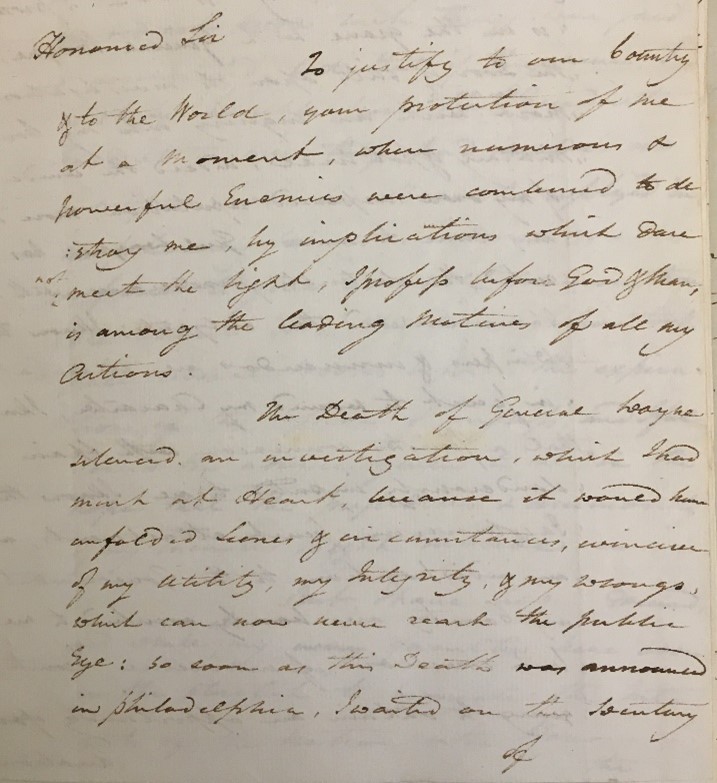

Abigail recommended the Letters to many in her orbit of influence, including her son John Quincy Adams, who took a copy on the boat to St. Petersburg. On 11 August 1809, he recorded in his (free and fully accessible online) diary, “The Night was almost entirely calm— I employed much of it in reading Mrs: Grant’s letters, which I find more interesting than Plutarch— I return to them of choice.”

We’ve all had a book find us when we needed it most. In the spring and summer of 1809, Abigail had her daughter move to the backwoods of New York, her son leave for the other side of the world, and with her 65th birthday rapidly approaching was feeling the weight of her years. “The more I read, the more I was delighted,” she confided to Nabby, “until that enthusiasm which she so well describes, took full possession of my soul, and made me for a time forget that the roses had fled from my cheeks, and the lustre departed from my eyes.”

“I long to communicate to you this rich mental feast,” Abigail wrote. And so I communicate it to you, dear reader. Meet you next month to discuss the Letters and to delve into John Adams’s retirement reads!

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund, with additional contributions by Harvard University Press and a number of private donors. The Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Historical Publications and Records Commission also supports the project through funding for the Society’s digital publishing collaborative, the Primary Source Cooperative.