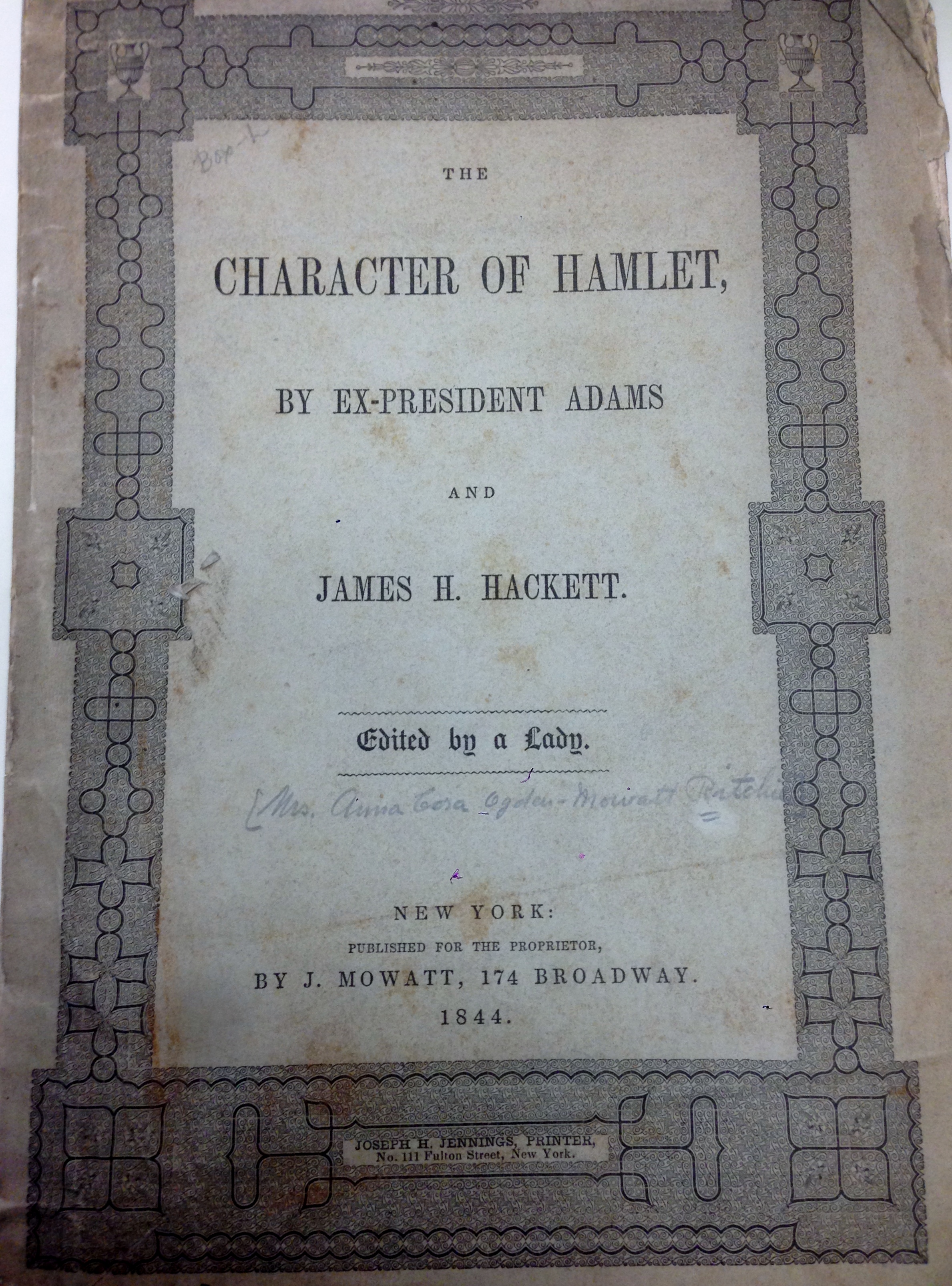

By Emily Ross, Adams Papers

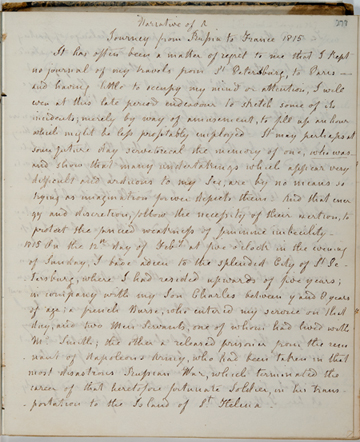

In an 1839 letter, John Quincy Adams stated his view that Shakespeare’s Hamlet was “the Master Piece of the Drama … I had almost said the Master Piece of the Human Mind.” He then gave an analysis of the play sufficiently scholarly and insightful that his letter and his correspondent’s reply were published as a pamphlet in 1844. A copy of this item is among the holdings of the MHS.

The front page of John Quincy Adams’ published interchange of correspondence with James Hackett, regarding the character of Hamlet.

While this publication may be the culmination of John Quincy’s preference for Hamlet, it is certainly not the only evidence of it: his admiration for the play is long-standing.

According to his diary, he saw the play at least seven times, and recalled the productions well enough to contrast the performances of different actors in the leading role. He wrote entries about attending performances on 16 May 1790; 30 November 1792, when the lead actor was “superior to my expectation”; 21 April 1794; 5 October 1797; 18 October 1799, when the lead acted “not well”; 17 April 1809, when the lead actor had “the promise of great powers”; and 13 August 1822, when he judged that the lead actor played Hamlet “indifferently.”

It is notable that the April 1809 Hamlet was the first play that John Quincy and Louisa Catherine took their sons George and John to see, at ages eight and six respectively. A challenging play for children to understand, it is not surprising that the boys had many “remarks and questions” during the performance.

Later that same year, John Quincy and his family took a tour of the Baltic, and he created the following ink and watercolor picture of Cronburg Castle–better know as Shakespeare’s Elsinore.

Kronburg Castle, Helsingør, 2 October 1809, ink and watercolor picture in John Quincy Adams, Miscellany 5, Adams Papers.

It is unclear at what age John Quincy himself first saw Shakespeare on stage, but he had already read some of the works by the time he was ten. An avid reader, he reported to John Adams in October 1774, “I read my Books to Mamma.” While reading aloud was presumably for educational benefit at this point, in adulthood it was instead a form of entertainment—and what better to read than Hamlet? John Quincy Adams noted in his diary that he read Hamlet aloud in 5–6 October 1799, 3–9 August 1802, 16–18 January 1804, and 3–4 March 1823. As the date ranges show, these play readings would extend over several nights, like a mini-series. Twice John Quincy was the only reader, but in 1799 and 1823, he was one of two readers. One wonders how he would have reviewed his own performance…