by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

Have you ever wondered about the origins of the everyday technological devices that we take for granted today? How far back do these devices go? What did some of their earliest incarnations look like?

The newly processed papers of Charles Francis Adams give us an idea. You may recognize his name, but no, I’m not talking about the ambassador to the U.K. during the Civil War (CFA 1807-1886), the railroad executive and historian (CFA 1835-1915), or the Secretary of the Navy and yachtsman (CFA 1866-1954). He was, however, a member of the same illustrious family and a direct descendant of Presidents John and John Quincy Adams.

Our Charles Francis Adams (1910-1999) was, among other things, a Navy veteran, vice president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and executive at Raytheon for many years. It’s this last role I’d like to highlight in this post. Raytheon, founded in 1922, has been headquartered in Cambridge, Newton, Lexington, and Waltham, Mass. Between 1947 and 1975, Adams served alternately as vice president, president, and chairman of the company.

Adams’ papers include 15 scrapbooks of newspaper clippings, photographs, and ephemera going back to 1920 that document much of the history of Raytheon. Adams’ tenure coincided with a period of explosive technological innovation, and while the company has become one of the country’s foremost military contractors, it was also involved in the development of a variety of commercial technological gadgets and home appliances in the post-World War II years. I want to focus on three devices: the microwave oven, the television, and the walkie-talkie.

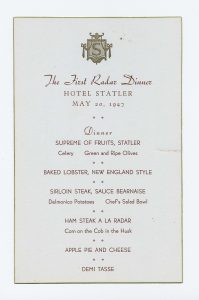

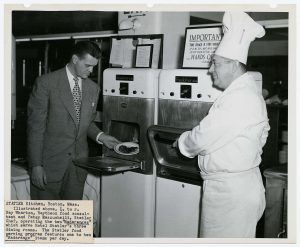

On 20 May 1947, the Hotel Statler in Boston (now the Park Plaza Hotel) debuted a new appliance manufactured by Raytheon—the “Radarange.” It was about five feet high, stainless steel, and used a magnetron tube for cooking meals in a matter of seconds. That evening, an entire meal was prepared with this “radar cooking,” including “radar coffee.” According to a Boston Post article published the following day, “The Hotel Statler made epicurean history last night. […] It was the first time this has been done anywhere.”

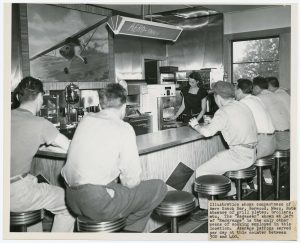

The scrapbooks include some fun promotional photographs featuring the Radarange at the Statler and other Massachusetts locations, like the Aero Snack Bar, a lunch counter at the Norwood airport; White Tower Restaurant in Brookline Village; and United Farmers Dairy Store in Dorchester.

One article estimates that there were about 75 Radarange units in operation by early 1948, mostly in hotels and restaurants. The appliances were not sold, but leased to customers for $150 a month. They were also intended for trains, ships, and even planes. Radaranges were not ready for everyday home use yet—for one thing, they were too expensive to make and to service—but Adams saw the potential in the domestic market, and by the mid-1950s, the company was developing a smaller model for direct sale.

The chairman of the board of Hotels Statler Co., quoted in a press release, said that the Radarange “has a definite place in the preparation of quality food in quantity production. The cooking is not only fast, it is clean—there is no grease, smoke or odor. Our chefs, furthermore, are delighted because ‘Radarange’ produces no external heat, making the kitchen a more comfortable place in which to work.”

What was the public’s reaction to this new-fangled contraption? Tide magazine, a publication covering advertising, marketing, and public relations news, said the Radarange was the “most intriguing” of Raytheon’s new products (30 Jan. 1948). A reviewer, early the following year, called it a “spooky invention,” but was otherwise positive about it. Christian Science Monitor summed it up this way: “At first there was some opposition to radar ranges because of the revolutionary changes in cooking methods implicit in them. Some cooks were impatient of the new techniques and others expected too much” (1 Apr. 1954).

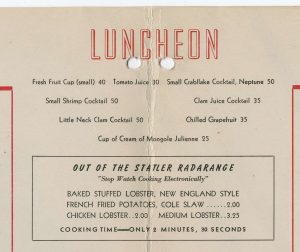

I, for one, love the idea of diners at a high-end restaurant ordering a microwave meal. In fact, the Statler reserved a special section on its daily menu for food prepared via Radarange.

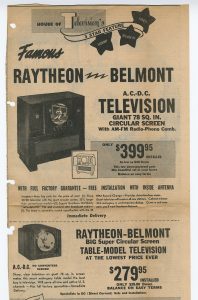

Television, on the other hand, had been around for a little while before Raytheon got in on the game. The company’s foray into the TV market wouldn’t last, but in the late 1940s, Raytheon and its subsidiary Belmont Radio Corporation were hyping their new model with features like a clearer picture, static-free sound, and a “snap-action station selector” (the channel dial, I assume). Prices of televisions advertised in Adams’ scrapbooks ranged from $200-$750. A store in Boston called the House of Television was selling a set that came in a mahogany cabinet with a AM/FM radio and a record player. It also boasted a “giant” circular screen…about 8.8 inches in diameter.

Last but definitely not least, I stumbled across these terrific clippings from the Quincy Patriot Ledger and the Boston Globe dated 4 Feb. 1952.They showcase Raytheon’s new “handie-talkie” radio, “the lightest and most compact hand radio receiver-transmitter ever developed,” weighing in at a mere 6 ½ pounds and larger than a woman’s head.

This radio, officially named the AN/PRC-6, was already proving useful to American troops in Korea. It could be submerged in water and withstand extreme temperatures, had a greater range and far more available frequencies than the previous version, and the 3 ½-pound battery lasted about 100 hours. As for its size, well, it was definitely an improvement over the 11-pound World War II “handie-talkie.” One writer astutely observed that this model was part of “the continuing miniaturization of communications equipment.” Imagine what they’d say about today’s hand-held devices.

All of the excerpts and images in this post were taken from the Charles Francis Adams scrapbooks here at the MHS. Click on any of the images above to see them larger. Or better yet, visit our library and take a look at the originals.