By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

Have you ever wondered what Abigail Adams’s favorite song was? Or maybe you wondered if John and Abigail had a song that was their song. A series of letters written between 1778 and 1787 seems to provide the answer.

Abigail Adams had an established affinity for “Scotch” songs. She was moved by the “Native Simplicity” of the lyrics and thought they had “all the power of a well wrought Tradidy.” While John was overseas serving as a commissioner at Paris, Abigail and her two youngest sons, Charles and Thomas, were fending for themselves in one of the severest winters Braintree had ever known. Abigail’s daughter, Nabby, was staying in Plymouth with friends, and her eldest son, John Quincy, was in France with his father.

“How lonely are my days? How solitary are my Nights?” Abigail wrote to her husband on 27 December 1778. “Secluded from all Society but my two Little Boys, and my domesticks, by the Mountains of snow which surround me . . . I am solitary indeed.” Someone Abigail identified only as a young lady found her in the midst of “a Melancholy hour” and decided to sing to her to cheer her up. That was when Abigail first heard the song “There’s Nae Luck about the House”—a song she would fondly cite again and again over the years.

The traditional song, attributed to Jean Adam, tells the story of a wife excitedly greeting her seafaring husband, or “gudeman,” after he’s been “awa’.” Abigail, deeply moved by the sentiments of the song, begged for the music. Her son Charles, then eight years old, learned the song so that he could sing it and console Abigail whenever she needed.

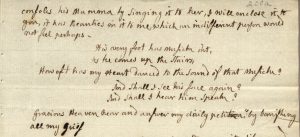

Abigail enclosed the music in one of her letters to John, telling him “It has Beauties in it to me, which an indifferent person would not feel.” She drew out several couplets that she found particularly relatable: “His very foot has Musick in’t, As he comes up the stairs” as well as “And shall I see his face again? And shall I hear him speak?”

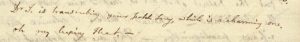

On 13 February 1779, when John received the music in France, he was similarly affected. “Your scotch song . . . is a charming one. oh my leaping Heart.”

Abigail’s affection for the song was shared with her dearest friends. On 15 March 1779, Mercy Otis Warren wrote to her, “You May feelingly join with me and the Bonny Scotch Lass, and Warble the Mournful Chorus from Morn to Eve. Theres Little pleasure in the Rooms When my Good Mans awaw.”

In 1785, when Abigail tried to illustrate to her teenaged niece Lucy the importance of expressing genuine sentiments simply, she referenced the song again. “It is that native simplicity too, which gives to the Scotch songs a merit superior to all others. My favorite Scotch song, ‘There’s na luck about the house,’ will naturally occur to your mind.”

A year later, while living in London, Abigail learned that her family back home in Massachusetts “were all turning musicians.” Her niece was becoming adept at the harpsicord, her nephew had taken up violin, and John Quincy and Charles were learning the flute. “Our young Folks improve fast in their musick,” her sister reported in May 1786. “Two German Flutes, a violin and a harpsicord and two voices form a considerable concert.”

Though she was now reunited with her husband and daughter, Abigail’s family was still separated by the Atlantic Ocean. “Here you would have felt a pleasure which you never experienc’d in a drawing Room at St James,” her sister wrote on 14 July 1786. “To vary our Scene musick is often call’d for . . . and then my sister how do I Wish for you. No one ever injoyd the pleasures of young People more than you use’d too.”

Abigail couldn’t join their late night concerts by the fire, but she came up with a way to make her presence felt. In the winter of 1787, she received a letter from home: “The musical society at Braintree return their thanks for those Scotch Peices of Musick whih you so kindly Sent them.”

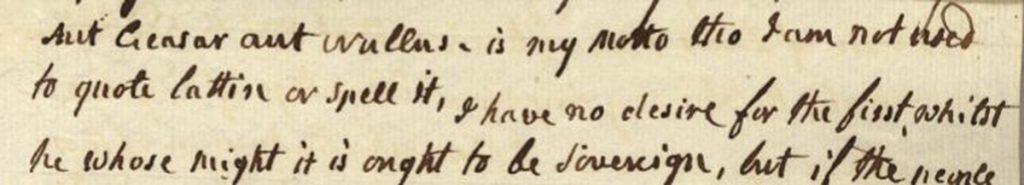

Left:

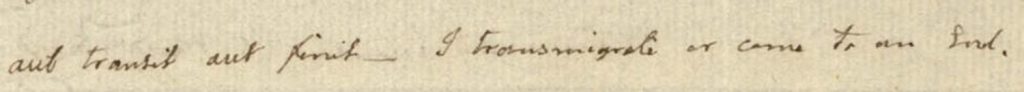

Left: