By Rakashi Chand, Reading Room Supervisor

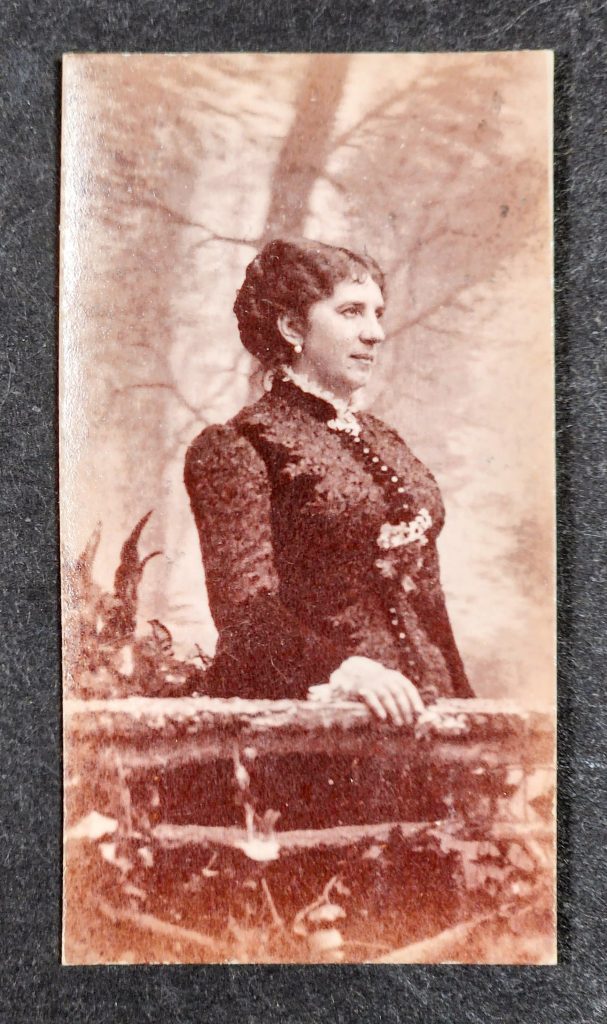

Dear Gentle Reader, although you and I may have never heard of Miss Elise Hensler, a woman infamous in Milan for her operatic prowess, and her daughter born out of wedlock, she caught the attention of a King and is now a Countess! Young ladies may read her story and swoon, but it was not all a fairytale ending.

Elise was born in Switzerland, but her family moved to Boston when she was young. She received a stellar education in the arts and languages, excelling in both. As a young adult, it was apparent that her voice deserved a European education, and off she went to Paris, bidding her sister and parents a fond farewell. Elise embarked on a European adventure unlike any other. While her family received regular letters and visits from Elise, their own heartbeats increased as they heard details, and tales, of Elise’s life in Europe. A gifted young opera singer, Elise joined the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. Her lure was undeniable and at the tender age of nineteen Elise gave birth to her daughter, Alice. The bond between mother and daughter was lifelong, even as Elise’s own life was about to change dramatically.

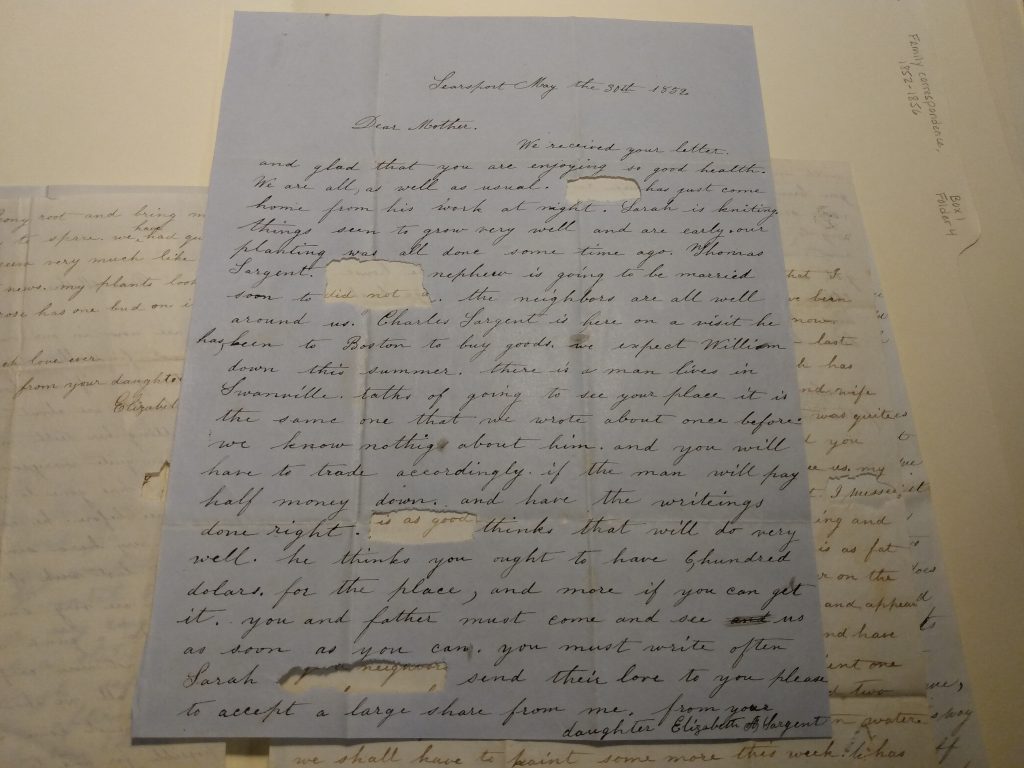

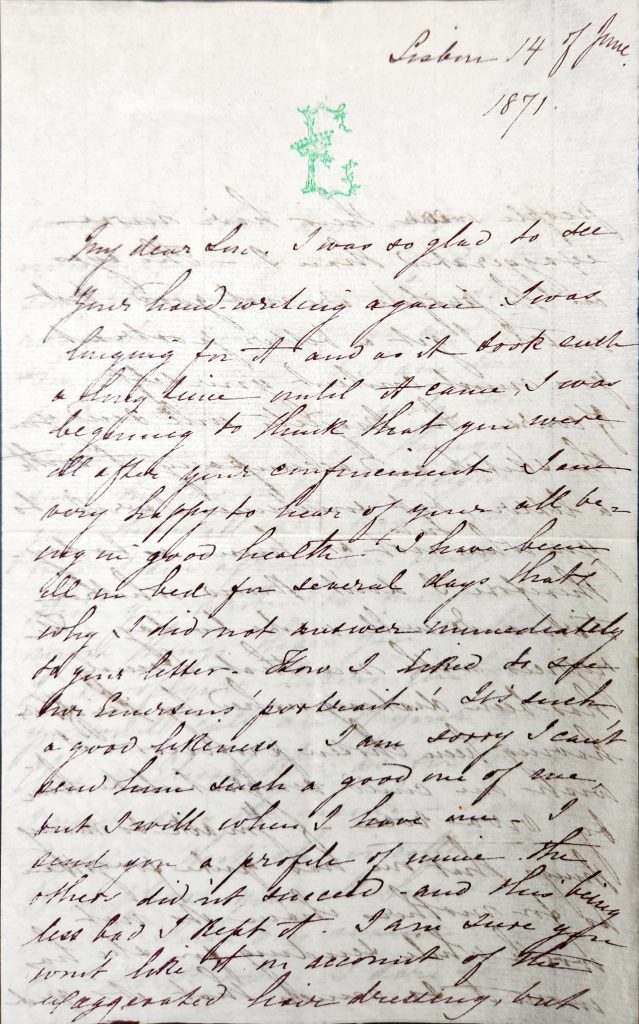

Elise’s sister was Mina Louise Hensler, who married Daniel Denison Slade in 1856, a doctor of medicine, but was also an expert in horticulture and zoology. Mina and Daniel had twelve children and lived in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. The letters between Elise and her sister Mina are among the many letters in the Slade-Rogers Family Papers at the MHS. Nineteenth century life In Chestnut Hill was pleasant, but the letters arriving from Portugal must have been enthralling, and indeed everyone waited for word from Elise.

Starting in February of 1860, Elise performed at the Teatro Nacional Sao Joao in Oporto Portugal, followed by the Teatro Nacional de Sao Carlos in Lisbon. On April 15th, 1860, Elise performed Guiseppe Verdi’s opera A Masquerade Ball, and captivated an audience member, King Ferdinand II of Portugal. Ferdinand was king-consort and widower of Queen Maria II, a prince of the royal house of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, nephew to Ernest I and King Leopold I of Belgium. Ferdinand was known as the King-Artist, a patron of the arts and an artist himself, educated in music and drawing, and fluent in multiple languages.

Soon Ferdinand and Elise were unabashedly in love and shared common interests in language, architecture, gardening, painting, ceramics, sculpture, and arts. Their courtship withstood the scrutiny of Portuguese society, and nine years later, the letter announcing their marriage finally arrived in Chestnut Hill.

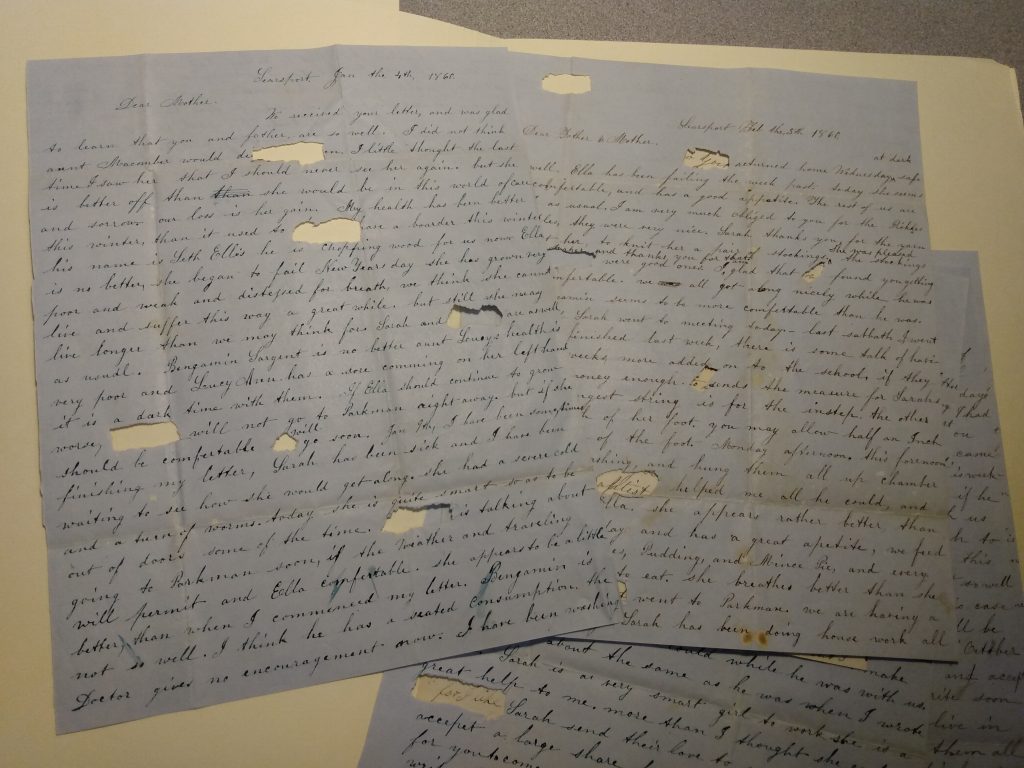

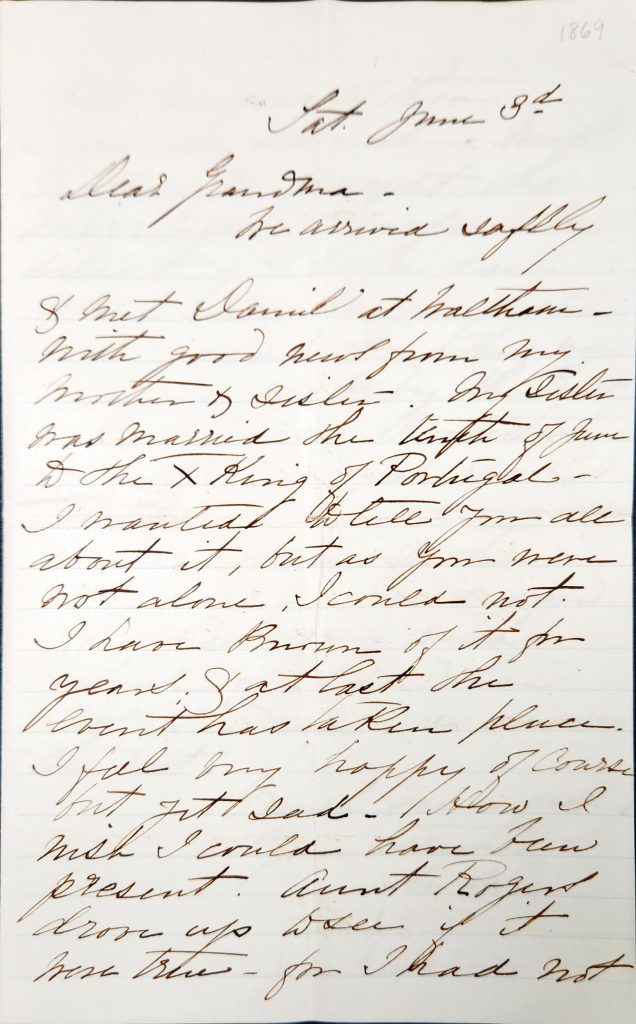

On Saturday, June 30th Mina writes with great excitement to Grandma:

Sat. June 30

Dear GrandMa,

We arrived safely I met Daniel at Waltham-With good news from my mother and sister. My sister was Married the tenth of June to the X King of Portugal–I wanted to tell you all about it, but as you were not alone, I could not. I have known about it for Years. & at last the Event has taken place. I feel very happy of course But [a bit] sad–How I Wish I could have been Present. Aunt Rogers drove up to see if it Were true–for I had not told any of them.

I feared something might Happen to prevent the Marriage–therefore kept Silent-I hope daily now to hear more particularly about it. They were Married first by the Priest And then by her Protestant Minister. I feel so glad at last …

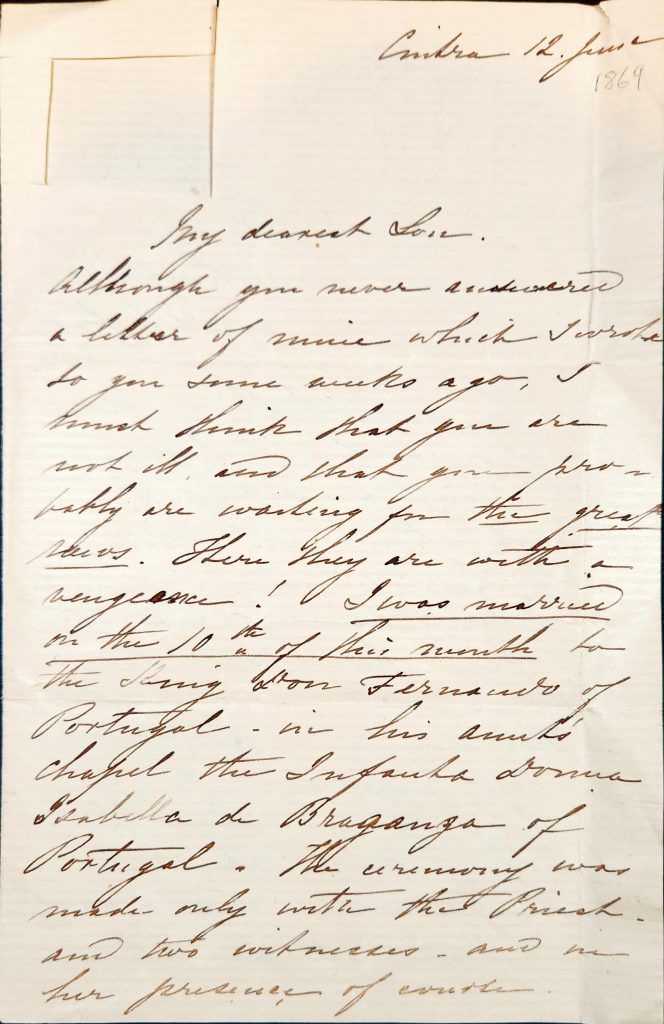

And the very next letter in the folder, sent on June 12th, 1869 (received on July 5th in Chestnut Hill) were the particulars Mina was waiting to hear…

My dearest love,

Although you never answered a letter of mine which I wrote to you some weeks ago, I must think that you are most ill and that you are probably waiting for the great news. Here they are with a vengeance! I was married on the 10th of this month to the King Don Fernando of Portugal – in his Aunts’ Chapel the Infanta Donna Isabella de Braganza of Portugal. The ceremony was made only with the Priest and two witnesses – and in her presence of [court?]

It was her Royal Highness that arranged everything- for it’s not an easy matter for a King to marry a protestant when he is Catholic – now my dearest love I hope you and Daniel are satisfied! This act shows you what a noble hearted man is the King for I never [live] any acts of my life [from] [him] , and his thinking and worthy of [his] makes me more happy than you can imagine – you can easily imagine what the feelings of mother are! – how my dearest – Kiss Daniel for me – and all your children.

I forgot to tell you that after the ceremony in the Catholic Chapel, was over, we returned to the [strong] Palace, and there we went through the protestant ceremony of marriage – you can have nothing to say to that now I hope – try and get well over you Family Way* andthen come and pay a visit to your sister, the Countess of Edla! This title was given to me by the Duke of Ernest of [ Caboung?] – [condrine] to the King, and [twas?] the head representative of the King’s family [(My king I mean?)]

I suppose you won’t resist the temptation to have this printed in the papers, but please do it simply, without my comments.

Mother is very happy- I hope you are [so do?] when you read these news – write to me immediately – put you letter in an envelope addressed to me

My happiness

Would be so great

Could I kiss you – I hope

It may be soon-

Love me and believe me ever you affect sister

Elise D’Edla

Because Elise was a commoner, she was given the title of Countess of Edla on her wedding day, allowing the King to marry her. The media tried to portray Elise poorly as a single mother in a 19th century European Court, but she was talented and capable, rising above the rumor mill. However, she was never fully accepted as Ferdinand’s wife and was ostracized and scrutinized by the Portuguese Court. Elise fought endlessly with the media’s portrayals of her life, and unlike any fairytale, she was often lonely.

King Ferdinand named Elise universal heir to his properties and estate, including the Royal Palace. When he died on December 15th, 1885, Elise was thrust into a years-long battle with the Royal family. Intimate details of the battle for the estates are found in the collection held at the MHS. In the end, Elise chose to live with her daughter, Alice, and her son in law, in Portugal, never to return to Boston. Her simple epitaph reads: “Here lies Elise Hensler, widow of His Majesty King Ferdinand II of Portugal, born in 1836 and died in 1929”.

What does modern Portugal and its tourism industry owe to Elise, the Bostonian, who could have claimed the Royal palace and all properties as her own? Over the years she worked to promote the arts and culture in Portugal, and as historians look back, her influence on modern Portugal is becoming more apparent. From benefactor of the Park of Pena to patron of Portugal’s modern masters, Elise continued to work towards the expansion of art, music and the preservation of architecture. Discredited, ostracized, criticized, but secretly admired, Elise was a Boston girl who fell in love with a king and his country. It is time for Elise to take her place.

Visit the Library of the Massachusetts Historical Society to learn more about Elise and read about the battle over her inheritance.

Hopefully, the readers of this lurid tale of love, loneliness, and the trials of a Countess has entertained and delighted. Sincerely, Lady Chand.

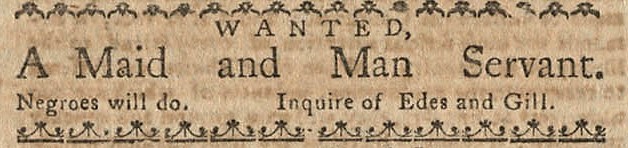

![A clipping from the Boston-Gazette and Country Journal. The advertisement reads “to be sold on board the sloop London Expedition, Nicholas Chevalier, Master, laying at Wibert’s Wharf, New-Boston. A Number of Indented [Indentured] Jersey Servants of both sexes: Likewise a quantity of cordage of all sorts, and hosiery.](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/indented-servants.jpg)

![Two clippings from the Boston Gazette and Country Journal. In the first Isaac Kingman “warn[s] all persons not to trust [his wife Ruth Kingman] on [his] account also to forbid all persons trading with her or purchasing any of my goods or chattels of her” in response to her “refus[ing] to remove and live with me as she ought to do.” In the second a husband forbids people from “trusting [his wife Sarah] on [his] account” as she “hath behaved in a vile manner, keeping company with wicked men.”](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Wayward-Wives-1024x285.jpg)