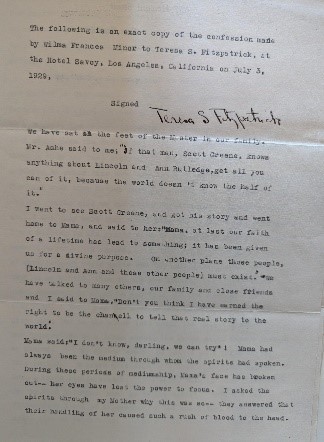

by Rakashi Chand, Reading Room Supervisor

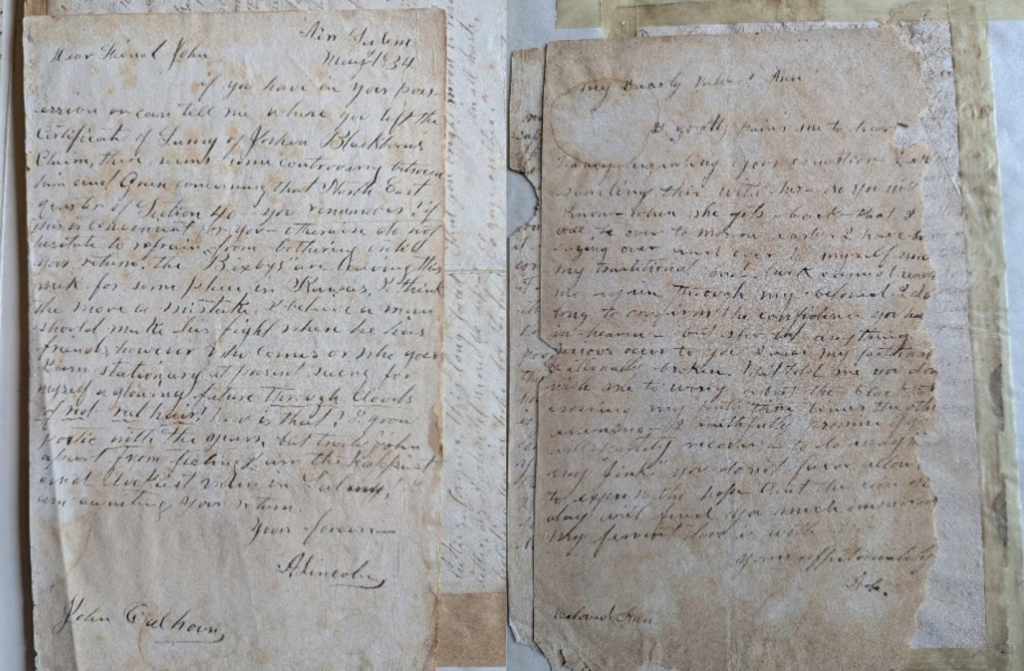

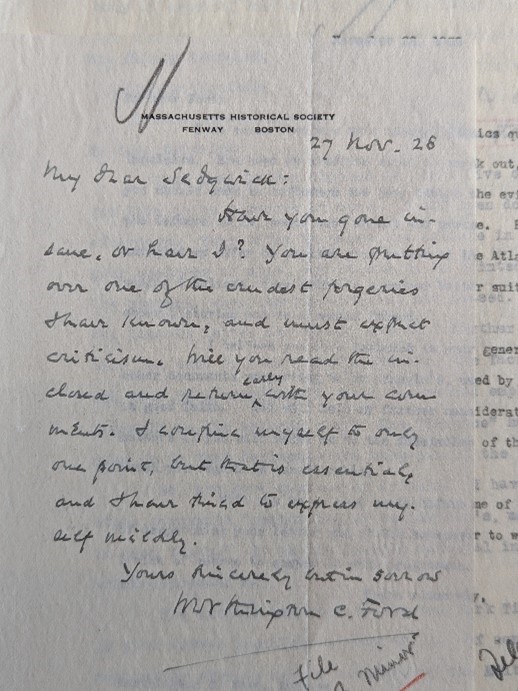

The campaign trail is heating up and the candidates are crisscrossing the country trying to win over voters. During a similar moment in history the elected Vice President suddenly had to step in as POTUS. On the subsequent campaign trail, he was almost killed in a 20mph collision with a trolley. The bizarre incident can be found in the Papers of Winthrop Murray Crane at the MHS.

After McKinley’s assassination on 14 September 1901, the nation reeled, and 42-year-old Theodore Roosevelt suddenly became President of the United States. Roosevelt hit the campaign trail in 1902 to win over the nation as President and campaign for his party platform before the congressional elections.

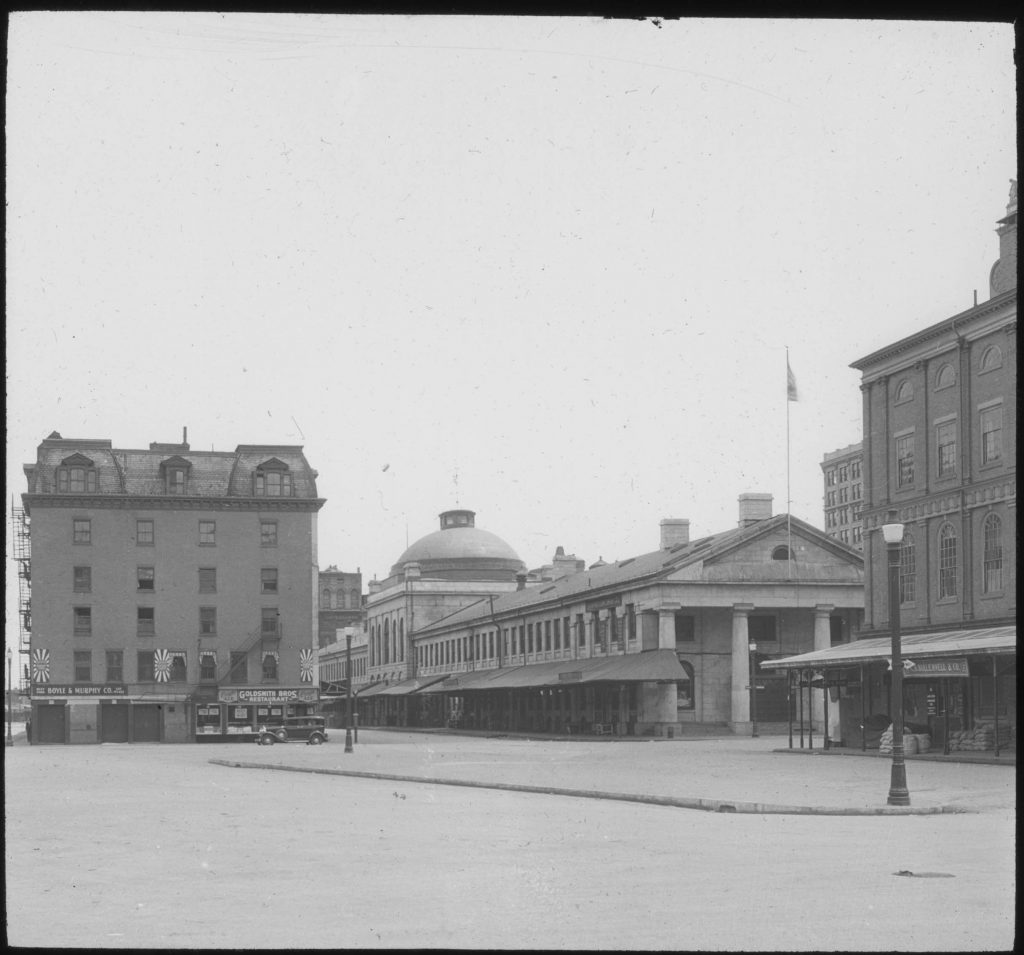

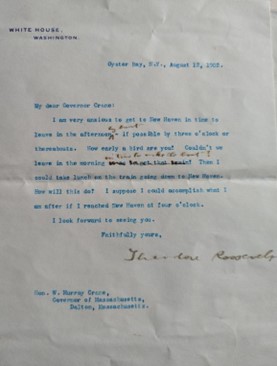

Roosevelt arrived in Bangor, Maine on August 27th with an entourage of more than fifty newspaper reporters, photographers, telegraphers, politicians and secret servicemen. He made his way through Vermont and crossed into Mass. where he met Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge. In Springfield Mass., Roosevelt delivered a speech defending America’s actions in the Philippines, specifically targeted to persuade the Mass. opponents of those actions. On the morning of September 3rd, Roosevelt gave a ten-minute speech on citizenship in Dalton, and was joined by Mass. Gov. Winthrop Murray Crane as they headed to Pittsfield, Mass.

Roosevelt’s handsome pullman carriage, the Mayflower, was waiting for him in Stockbridge. Crane and Roosevelt rode in his open carriage to Pittsfield, accompanied by Roosevelt’s secretary, George Cortelyou, and Secret Service Agent William Craig. The four horses were driven by Crane’s friend, Deputy Sheriff David Pratt, with mounted troops on each side. Roosevelt would have had the opportunity to enjoy some Berkshire scenery knowing that the press and the public were becoming more enamored with each speech and stop along the way.

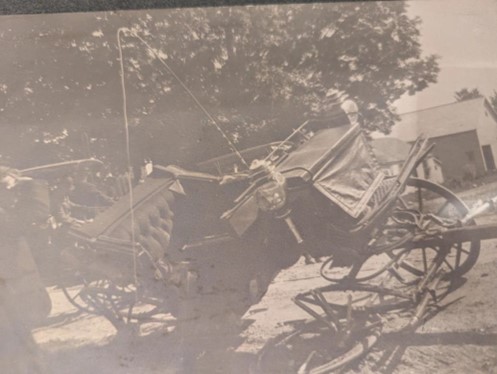

At 9:35 AM a trolley became visible to the carriage that remained on the right of the trolley tracks, which seemed inconsequential as the Pittsfield Street Railway Company had been informed the regular schedule would be interrupted during the President’s visit, but the motormen running the trolley had been told to run as long as it was still possible. Why was this trolley on the track? Apparently, it was full of members of the Pittsfield Country Club who asked the motorman, Euclid Madden, to get to the Country Club before the President in a desire to receive him. Clearly there was a lack of communication. But what happened next was inexplicable. Pratt suddenly moved the carriage to the left, across the trolley track, perhaps, it is thought, for shade. Pratt’s peripheral view would have been obstructed by the mounted troops on each side of the carriage.

Roosevelt was confident the trolley would stop to let the Presidential caravan pass; Crane was not so confident and began waving his arms at Madden and the impending trolley. Madden tried everything he could to stop the trolley, including the brakes and shutting off power, but nothing could stop the trolley from crashing into the carriage. Madden contended afterwards that the trolley was only moving at eight miles per hour, although others felt it must have been moving at twenty miles per hour.

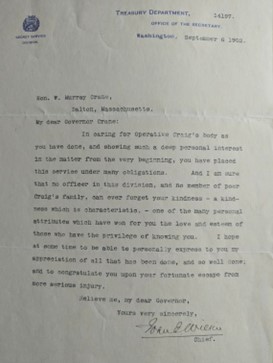

Witnesses describe a shocking silence after the collision. Both Crane and Cortelyou grabbed the president upon impact. Roosevelt hit the side door of the carriage, resulting in cuts, swelling, and bruising on his face and lower left leg—a leg injury that would continue to bother him for years. Cortelyou hurt his nose and head, but Crane was miraculously unscathed. Pratt was thrown to the front of the trolley, but with little injury. Craig, known as “Secret Service Man Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the President”, got up from his seat to shield the president and was thrown directly in front of the trolley as it charged forward. Craig was the first Secret Service agent who died protecting the President of the United States.

As the crowd rushed forward, the president and the governor held each other in shock. Roosevelt then became irate and perhaps uttered a profanity, but quickly gathered himself and assured the public that he was unhurt. He arranged to have Craig’s body moved to the nearby home of Mrs. A. B. Stevens and take Pratt to a hospital. The president, the governor and the president’s secretary were examined by doctors for thirty minutes in Mrs. Stevens’ house before limping out to the cheer of the crowds upon seeing Roosevelt intact, to which he responded “Don’t cheer. Don’t. One of our party lies dead inside.” (1)

Roosevelt knew the news of the accident could create rumors and potentially chaos in government, and asked reporters to spread word that the POTUS was unhurt and would continue onwards. Against all advice, Roosevelt pressed on and intended to make all scheduled stops that day, even with his bruised face, cut lip and black eye, lest the impact would be felt from Wall Street to foreign relations (2), although he gave no speeches.

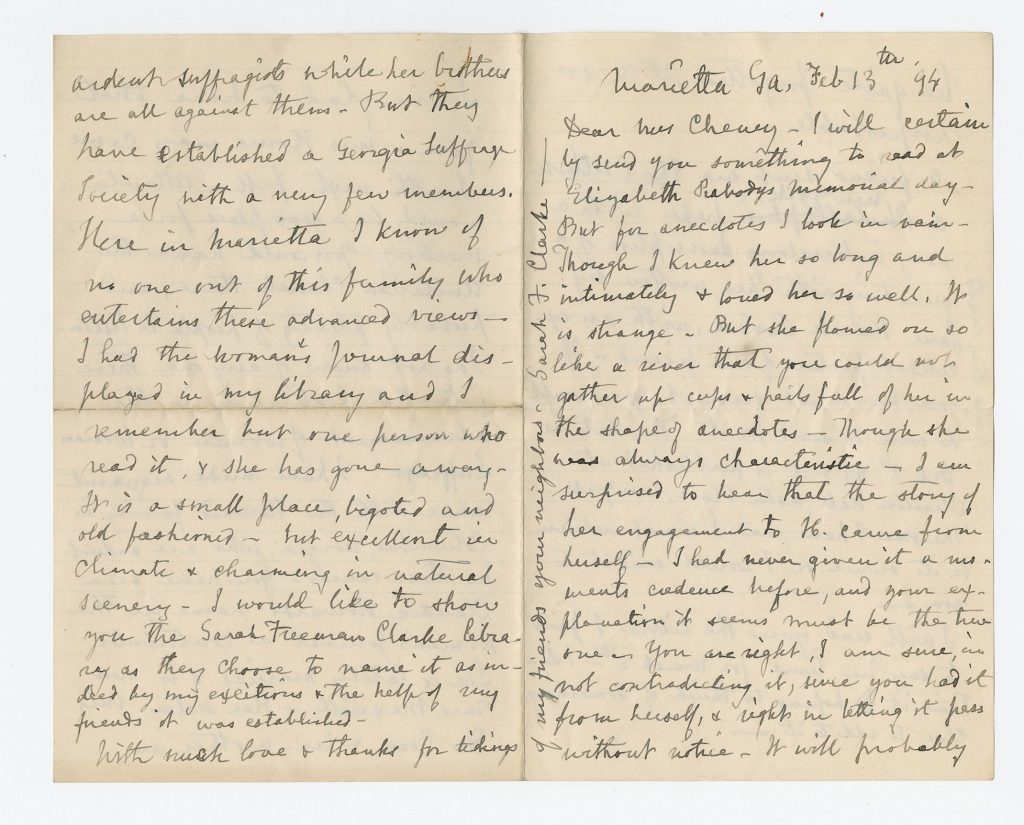

Winthrop Murray Crane, owner of Crane and Co., went on to have great influence on American politics. Crane settled the 1902 three-day Teamsters strike in two hours, prompting Roosevelt to call upon him to mediate the anthracite coal strike, and once again he settled the strike successfully. Roosevelt offered Crane several positions in his administration, but Crane refused them all until George Frisbee Hoar’s seat became available in the US Senate. Crane served as senator from 1904 until 1913.

PS: This was not the first, nor most meaningful, connection Roosevelt had with Mass.; Roosevelt attended Harvard College, and at the age of nineteen met the cousin of Richard Saltonstall, a fellow undergraduate, named Alice Hathaway Lee. (3) Roosevelt was madly in love with the beautiful, cheery Alice of Chestnut Hill, and vehemently sought her hand in marriage. Alice and Theodore married on his twenty-second birthday, October 27, 1880 in Brookline, Mass. Alice died four years later on February 14, 1884, two days after giving birth to their daughter. Roosevelt was so heartbroken he never spoke of her again, not even to their daughter, Alice.

- President Theodore Roosevelt’s Brush with Death in 1902. Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital- Library/Record?libID=o308081. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Theodore Roosevelt Papers: Series 2: Letterpress Copybooks, -1916; Vol. 36, 1902, July 29-Oct. 25. – October 25, 1902, 1902. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss382990364/.

- For more on Alice Lee Hathaway Roosevelt: TR Center – Roosevelt, Alice Hathaway Lee (theodorerooseveltcenter.org)