By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

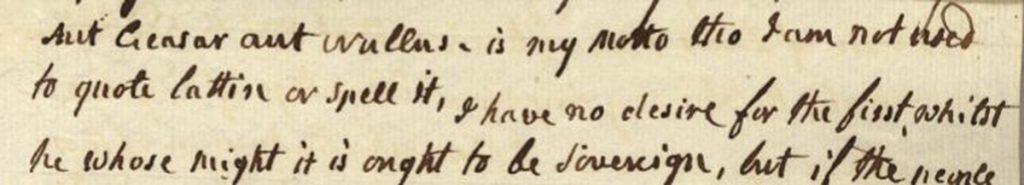

I should have written to you before this but thought I would wait untill I knew when I was going to war. […] I never have been sorry yet that I enlisted but think quite likely that I shall be before I get back if I ever do. I hope we shall not be gone long and will all come back safe and sound. You must not worry any at all about me while I am gone…

I’d like to take this opportunity to introduce our readers to another terrific collection of Civil War papers here at the MHS, the Dwight Emerson Armstrong letters. The collection is very small, consisting of just 38 letters written between 13 June 1861 and 27 April 1863, but the content is so interesting that I thought I’d start a short series here at the Beehive to talk about the story in more detail.

Dwight was born in the small town of Wendell, Mass. on 5 December 1839, the son of Deacon Martin Armstrong and Mary (Bent) Armstrong. Mrs. Armstrong died when Dwight was only four years old, and Martin remarried to a widow named Almira (French) Root. Dwight had three sisters, two brothers, and one half-brother. He was working as a laborer in Montague, Mass. when he enlisted on 19 April 1861, just one week after the attack on Fort Sumter. He was 21 years old.

All of the letters in the collection were written by Dwight to his older sister Mary. However, the letters came to us without envelopes, so her first name was all I knew, and it took a little time to track down more information about her. A 1900 genealogy identifies her as Mary Bent Armstrong, named for her mother. I finally found a footnote referencing her in a book called Wendell, Massachusetts: Its Settlers and Citizenry. Mary’s husband was a farmer named Emery H. Needham, and in 1861, they were living in Amherst, Mass. with their two young daughters, Annie and Jennie.

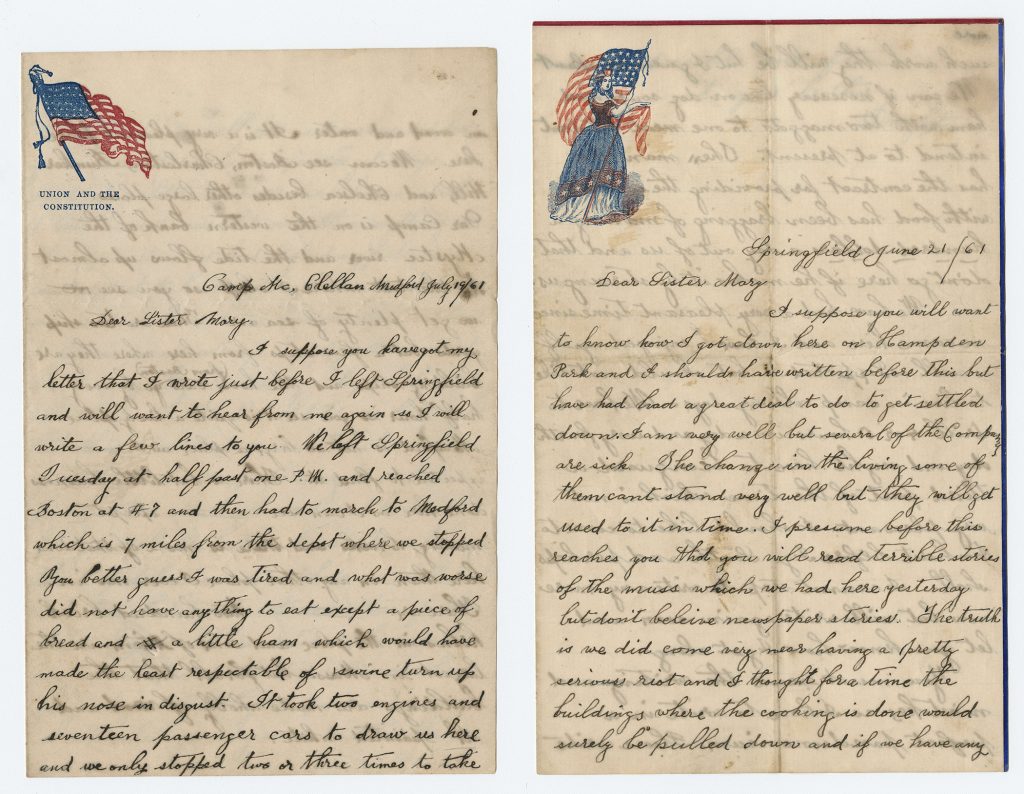

Some of Dwight’s letters are written on stationery decorated with colorful images of the American flag, Lady Liberty, etc. (Incidentally, the MHS holds a collection of over 1,000 Civil War “patriotic covers,” envelopes printed with pictures like these.)

The letter quoted at the top of this post is the first in the collection. Eight days later, on 21 June 1861, Dwight was mustered into service as a private in the 10th Massachusetts Infantry, Company G. His regiment was mobilized at Hampden Park, a repurposed racetrack in Springfield, Mass. In his second letter to Mary, written that day, Dwight described life in camp as “a perfect pandemonium.” This pandemonium included some discontent over the army’s less-than-stellar provisions.

I presume before this reaches you that you will read terrible stories of the muss which we had here yesterday but don’t beleive newspaper stories. The truth is we did come very near having a pretty serious riot and I thought for a time the buildings where the cooking is done would surely be pulled down […] We can if nesessary live on dog soup and ham with two maggots to one meat but dont intend to at present.

For context, I consulted two printed histories of the regiment, Joseph K. Newell’s “Ours”: Annals of [the] 10th Regiment (1875) and Alfred S. Roe’s very similar The Tenth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (1909). Both downplay this incident as nothing more than young men bristling at the restrictions of army life, or, in Roe’s words, “the unwillingness of Young America to submit to meets and bounds without some sort of protest” (p. 13-14). However, the discontent was real, and desertion was already becoming a problem. In his next letter, Dwight elaborated.

A good many have run away and I suppose they are afraid the rest will if they get a chance. As the time when we are to start comes on some begin to think they had better have stayed at home and a double guard is placed around the Park every night to keep them where they belong.

Regimental rosters in both Newell and Roe indicate that many soldiers did, in fact, desert during the short time the 10th was stationed at Hampden Park.

Dwight himself seemed relatively sanguine about his enlistment. July 1861 was “terrible hot,” but he was “tough as a knot.” He reassured Mary that “I guess I shall stand it as long as any of them.” He did complain about the drilling, guard duty, marching, and of course the food, but he kept it all in perspective.

We cant have a speck of butter and I miss that more than anything else. I suppose it is not best to find any fault for we cant expect to have anything as convenient as we would at home.

The 10th Massachusetts Infantry decamped on 16 July 1861 and began its long trip South. I hope you’ll join me in a few weeks to hear more of Dwight’s story.