by Hannah Elder, Library Assistant

Today I want to share some letters that were written in a place close to my heart: my hometown! They were written by Capt. John Binney while he served as the commander at Fort Edgecomb (in Edgecomb, Maine) in the lead up-to the War of 1812. The fort was built in 1808-1809 to protect the port of Wiscasset, then a busy shipbuilding center. Binney, originally from Boston, lived in the neighboring town of Wiscasset while the fort was under his command and he frequently wrote to his brother, Amos Binney, while he was stationed there. John’s letters to Amos can be found in both the Binney Family Papers and the Henry P. Binney Family Papers at the MHS.

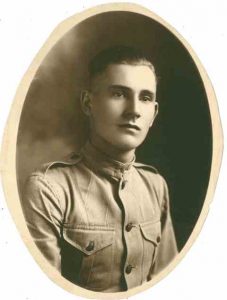

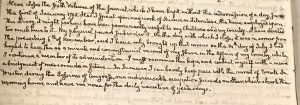

John Binney served as the captain of the 4th Regiment, U.S. Infantry at Fort Edgecomb from 1809 to 1813. When he arrived, he was not impressed with the men in his regiment or with the people of Wiscasset. Upon his first inspection of his men, he wrote to Amos:

27 fine hearty young men immediately appeared on parade but as dirty, pybald, ragged and as gawky as you please. Ten thousand harlequins – Twenty thousand Rainbows, or thirty thousand ribbons shop would not have displayed half the variety of colors as their dress did

The differences between this Boston army captain and the people in the rural shipping port became very apparent to John the first time he wore his full dress uniform in town. He was “absolutely astounded” by the reactions of the townspeople, who gawked at his “pretty boots,” feather, and sword.

He spent much of his first years in Wiscasset equipping his men and the fort. Many of John’s letters to Amos included instructions on what to send to Wiscasset, how to manage his Boston household on his behalf, and discussions of his business.

When war was declared in June of 1812, John was informed by letter. On June 27, he wrote to Amos:

I received an express on the 23rd at 5PM with notice of the Declaration of War. I immediately sent express to Georgetown, Damariscotta and Ft. George and in half an hour was ready to commence action, El W Ripley commands from Saco to Passamaquoddy Bays. Your department I expect will open the Ball and all must regret that more frigates was not built we shall feel the want of them – I have but 56 effectives at 5 forts from Castine to Kennebeck [sic] that more troops are necessary is ready seen. The militia will be called to our aid or should be – I have made the best display possible with my small force – am well armed and have powder and ball, but not enough should a ship of war attempt either of the Posts under my command the result is not doubtful. is should have to contend against fearful odds, six heavy guns is the most at either of my posts. A frigate would bring more than twenty to bear on my works – and then from a destruction I should least annoy, however I shall do all that can be expected with the force at the posts.

In the first few months of the war, John was concerned about the number of men at his command, sure that they would not be able to properly defend the towns under his protection. In August of 1812, he wrote:

It is a fact and I shudder when I think a Privateer with 100 men could destroy every port from Eastport to Portsmouth and Castine. I have 8 men at St George 8 men at Damariscotta 8 at Kennebeck [sic] 12 at this Post. 24 effectives – what could we do with this small force – little or nothing not one of the Ports being defensible on the land side – a small force in our rear would defeat or slaughter the whole with a few discharges of grape. And there is nothing prevent an Enemy from landing on the back of us – thus you see my means with more than 100 miles of coast under my command requiring 500 men at least to make a respectable defence but I shall endeavor to do my duty.

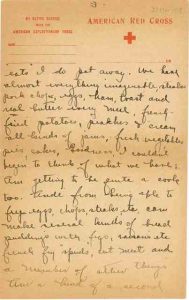

In September, though, he received orders to call new men to service. He told Amos:

I have this day been directed by Colo Boyd to call into immediate service at the Port and vicinity a volunteer company of Infantry under Capt. Daw Rose 84 strong – this will be quite an addition to my Garrison and if they prove good I shall feel much more at ease than I have for months past with 5 ports and sixty men

Luckily for John and his few men, Fort Edgecomb was never attacked during the war.

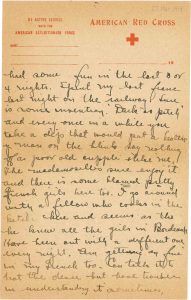

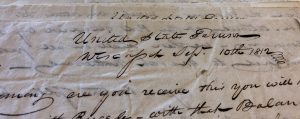

I really enjoyed getting to see what life was like in my hometown more than two hundred years ago, but more than that, I enjoyed getting to know John Binney. John was a diligent correspondent, always confirming that he had received Amos’s letters and passing along affection to his brother and the rest of his family. He had a quick wit and provided vivid descriptions of the people he met (one fellow who did not impress John was once described as “the most awkward styled two-legged unfeathered animal you ever saw”). I especially enjoyed the variation in the flourishes in John’s handwriting – it seems that when he was in a good mood, the flourishes were much more plentiful, like the one seen here:

If you would like to get to know the Binney family for yourself, or any one of the many fascinating people from our collections please consider visiting the library!