By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

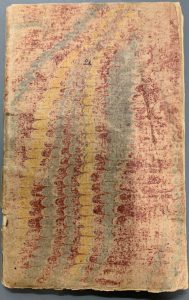

Today, we return to the diary of George Hyland. If this is your first time encountering our 2019 diary series, catch up by reading the January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, and October 1919 installments first!

November brings new rhythms to George’s workdays. With the harvest in for the season he turns to preparing fields and farmyards for the winter, beating rugs, cleaning windows, carrying ash, chopping wood, planting blubs, and selling junk to the local junk dealer. He observes Armistice Day — the one year anniversary of the end of the Great War — and Thanksgiving Day. Snow storms batter the coast and twice he goes to Egypt Beach to observe the high waters and waves. As we close in on the final weeks of 1919, we see George settling in for the winter ahead.

Join me in following George day-by-day through November 1919.

* * *

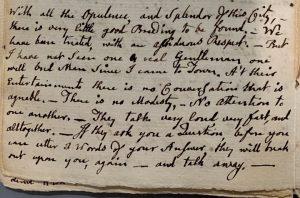

PAGE 350 (cont’d)

Nov. 1. Dug potatoes 5 1/2 hours for Mrs. Hazel Dimond (nee Reddy) – 1.65 and dug up and housed dalia [sic] bulbs 1h. 10m. for Mrs. Mary Wilder — 35. Cloudy W.S.W. and S. tem. 48-57. Eve cloudy, W.N.E. Played on the guitar 1h. 10 min. In eve. 9 P.M. light rain.

2d. (Sun.) rain until about noon; W.N.E. cold storm. Aft. clou. Eve. par. Clou. W.N.E. 11 P.M., nearly clear.

3d. Par. clou. To cloudy rain. 15 min. In aft. W.N.E. cold. Harvested my carrots and parsnips in my garden on the James place — had 2 1/2 bus. of carrots and 1 bu. And 1 peck of parsnips — gave Mr. James 1/2 peck of parsnips and carrots, all he wanted. Eve. clou. cold. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve. 11:50 P.M. par. clou. W.E.

4th. Election Day (State). Went to State Election in the Town Hall, Scituate Cen. Voted Republican ticket entire. Rode there and back with Fred T. Bailey — in his coach (close) automobile — Belva C. Merritt rode to her home with us. Mr. James rode back with us from S. Cen. In aft. Worked 3 1/2 hours for Miss Edith C. Sargent — cleared all the corn stalks, vines and etc. (50) and wheeled them into the swamp — dug up her dalia bulbs also some for Mrs. Eudora Bailey and put them in the cellar. Went into the house after I fin. the work — staid [sic] 1/2 h. Mrs. Bailey gave me some five pears (Bosc). Cloudy; W.E. began to rain about 5:30 P.M. rain all eve. W.E. cold. Played on the guitar 1h. 10min. late in eve. got in some of my wood — old boards, etc.

5th. Rain all day and eve. W.N.E. and N.W. windy. Worked in house to-day — got the rubber of of some elect. light wire — got the copper ready to sell. Got all my junk ready for junk dealer.

PAGE 351

Cold storm. Snow-storm for 1/2 hour about dark. Played on the guitar — 1 1/2 hours in eve. Rain and gale (36m.) all night.

6th. Cold. Very windy in forenoon. Max w. 36m. W.N.N.W. light rain all day and part of eve. Sold all my junk this aft. — to Samuel Benson, junk dealer. Played on the guitar 1 ½ hours in eve. Eve. cloudy, cold. Sold 30 pounds of rags and old cloth _ _ _ _ 30.

60 pds. of iron – 15.

8 pds. of copper — 88.

5 pds. of brass — 25.

7 pds. of zinc — 21.

2 1/2 pds. of lead — 7.

3 pds. of rubber — 8. — $1.94

7th. Clou. Cold misty rain in forenoon. W.N.E. Windy. Late in aft. Worked 1h. 55m. For Mrs. Ethel Torrey — sawed and chopped down the upper half of a cherry tree and sawed off some of the lower limbs — 55. Eve. clou. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. — also repaired some of my clothes. Made a wash tub in forenoon. 11 P.M., begins to clear. 11:42 P.M. circle around the moon for a few minutes.

8th. Worked 4 hours for Mrs. Ethel Torrey trimmed out the cherry tree wood and piled it up and carried the trash to a dump also dug up and transplanted 4 rose bushes — 1.20. Also split wood 3/4 hour for Mrs. Cora Bailey — 20. Clou in forenoon — clear at noon. Aft. clear to par. clou. W.E. to S.E. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Tem. to-day – 40-48.

9th. Sun. Clear. W.E. cold wind. Went to Egypt Beach, then walked along the shore — on the sea wall part of the way — to the glades — end of N.S. beach. Road badly damaged by the waves dur. the storm. Sea wall badly damaged in some places — […] damaged all along the shore, large number of people at the beaches — to view the waves and see the effect of the storm for the past 2 or 3 days. Water went under the “Merton” and comfort cottages, but did no damage to them. East wind cold at the sea shore. Ocean very rough. Walked all the way — 7 miles. Many automobiles along the shore rodes. 37 passed by me in 5 min — by my watch. Eve. clear. Calm.

10th. Worked 6 3/4 hours for Mrs. Bailey Ellis and B. Ellis — washing windows (outside) and dusting the rugs and carpets. Fine weather — clear; W.E. Very heavy frost this A.M. Eve. clear. Washed a blanket in eve — 1 hour then played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours. Heavy firing in directions of Boston — 8:30 to 8:45 P.M.

11th. Armistice Day. X Worked 7 hours for Mrs. Christine Ellis (nee Christine Bullard) washing and polishing windows and beating (dusting) rugs and carpets — 2.10. Evelyn Whiting also worked there for Mrs. Ellis. Was there yesterday too. Cloudy, W.S.W. and S.E. Very damp. Eve — cloudy, W.E. Played on the guitar 1 ¼ hours in eve. 12:20 (mid.) raining. | The Great War ended 1 year ago to-day. X

12th. Misty rain in forenoon. Aft. clou. W.S.W. did some work at home — washing and etc. Sold 14 ponds of rags to S. Benson — 14. Paid $1.00 this A.M. to Mrs. Bertha Bates (nee Hobson) as dues for Red Cross membership — for 1920. She gave me a Red Cross — design for 1920 — and a R.C. Button with date — 1920 on it. I joined the Red Cross in 1917. Dues — $1.00 per year. Mrs. B. is agent for this part of the town. Eve. cloudy. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Received a N.Y. “Sunday Times” from Lottie to-day — from Groton, Conn.

13th. Cloudy in forenoon. W.N.E. light rain in aft. Mrs. Ethel Torrey came here late in aft. To get me to make a garden for chrysanthemums. I went there to do it but it began to rain — W.N.E. and I came back. Cold storm all eve. Mrs. Christine Ellis paid me for all work I have done there — 13 1/4 hours in all $4.13. Did some work at home to-day. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in Eve. 11:30. Clear. Cold. W.N.W. windy.

14th. Worked 1 hour for Mrs. Ethel Torrey. Made a garden and transplanted some chrysanthemums in it — 30. Also worked 5 hours for S.T. Speare (his father) cleaned out a large poultry house (dust very plenty) and dug up the ground in a poultry yard — 4.50.

Ice this A.M. W.N.W. cold. clear. Ellery Hyland called here in eve. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve. Eve. clear. cold.

15th. Worked 5 hours for Mr. Speare — 1.50. Cold. Clear. W.N.N.W. Called at Mr. James’ early in eve to help Mrs. [space left blank for name] get her trunks ready for express — to carry to the R.R. Sta. She is going back to Seattle, Wash. to-morrow. A.M. Eve. cold. Clear. Lucine E. Bates spent eve. here. Mrs. Ethel Torrey gave me a pint of milk to-day. Washed some of my clothes early in eve.

16th. (Sun.) Clear. Cold. W.N.W.N. and W.S.W. tem. About 26-46.

17th. Worked 5 1/2 hours for Mrs. Christine Ellis — washing windows (2d story) also dusted two blankets — 1.65. Have washed 39 windows — 1st and 2d stories. Par. clou. W.S.W. tem. 42-50. Eve hazy. 11 P.M. Clear. Warm for season. Early in eve went to Mr. Albert D. Spaulding’s (1 mile) and paid my taxes — for 1918 — $15.14. Then went to Mrs. M.G. Seaverns’ store and bought some groceries — then went to W. Bates’ and got a bedstead (iron) that Mrs. Bertha Bates gave me to-day all before I had supper. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours. Ellery B. Hyland called here in eve.

18th. Worked 5 1/2 hours for Mr. James — housing wood and clearing up the place — fine weather — par. cloudy W.S. tem. 46-59. Miss Edith C. Sargent came to the place where I was raking leaves and said Mrs. Eudora Bailey would like to engage me to do the work there this winter — carry out the goal ashes — shovel paths when snow comes. She lives with Mrs. B. opp.. the James place. Played on the guitar 1 ½ hours in eve. Eve. clear. Tem. 46.

19th Worked 6 hours for Mr. Speare — diging [sic] up the ground in poultry yards and wheeling the best dirt down around the lawn, also put 8 loads around Mrs. Ethel Torrey’s shrubs and plants — 1.80. Cold and windy (N.W.) clear to par. Clou. eve. Clou. very windy and cold. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. 11 P.M. Snow storm tem. 28. Max. wind about 36m

20th. Worked 5 hours for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns — put on storm door, cellar windows and split 2 large logs — and sawed and split some of it. Swept snow from walks and […] and did some chores — 1.50. Cold and windy; W.N.W.; tem. 25-38. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Eve cold. Tem. 27.

21st. Worked 6 hours for Mr. Speare — cleaning boxes where he sets hens (incubator room) and diging up ground in poultry yard and wheeling it to a garden and spreading it on the ground — 1.80. Warmer to-day tem. 27-48; W.W. to S.W. eve. Cloudy. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. 11:30 P.M., clou. W.N.W.

22nd. Worked 6 hours for Mr. Speare — diging up ground in poultry yards and wheeling the dirt on to the gardens — 1.80. Mr. S. has many yards and a large number of hens and chickens. They are all Rhode Island Reds. Clear to par. Clou. W.S.W. to S. tem. about 40-60. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. 8:45 P.M., raining. Light rain all eve. Met Mrs. Bessie W. Prouty (nee Clapp) in Mrs. Seaverns’ store early in eve.

PAGE 352

23rd. (Sun.) fair. W.N.W. late in aft. Tem about 30-48. Went to Egypt Beach via […] Road and […] Hill — went to edge of water — dipped my hand in water when a small wave came up. Ret. through Egypt. Just 1 hour coming from beach to my home 3 1/2 miles. Did not hurry. Walked down and back. 3:20 P.M. to 5:30 P.M. Eve. clear to par. Clou. Boiled some turnips, carrots, parsnips, and beets in eve. From my garden at the James place. Also a few carrots from Mrs. Ethel Torrey’s garden.

24th. Worked 6 hours for Mr. Speare — diging up ground for a place to sow rye — 1.80. Clear. Cold. W.N.E. to N.W. Mr. [space left blank for name] Cluff, agent for S.S. Pierce & Co., large grocery dealers, Boston, called at Mr. Speare’s this forenoon — he wants me to do some landscape gardening for him next spring. Lives in Roxbury, Mass. Eve. clear. Cold. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve.

25th. In forenoon dug up ground 2 hours for Mr. Speare — 60. In aft. Worked 4 hours for Mrs. Ethel Torrey — trimming shrubs and etc. — 1.20. Fair to par. Clou. W.S.W. eve. Cloudy. Began to rain about 7:35 P.M. Light rain all eve. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. Rain all night (light rain).

26th. Rain all day W.N.E. In forenoon worked 2 hours for Mrs. Ethel Torrey — carrying coal ashes out of the cellar — 66. Got wet. Rain until about 11:30 P.M. Then clou. Colder. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve.

27th. (Thanksgiving Day.) In forenoon worked 1 1/3 hours for Mr. Speare — smoothing over the ground and sowing rye. Late in aft. | 40. Went to Hingham — on 4:12 P.M. tr. then walked to Hingham Cen. to Henrietta’s. Arr. 5:10 P.M. Carried my guitar — played 1 1/2 hours in eve. Uncle Samuel and Ellen there. They spent the day there. Frank carried them home about 6:30 P.M. in his automobile. I had supper and staid [sic] there all night. Cloudy. Very damp. W.E. Cold. Light snow storm in eve (late).

28th. Staid in Hingham. Worked 6 hours for Henrietta — 1.00 — helping Frank tear down a building. Cloudy to fair. W.E. Cold. In eve played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours.

29th. Staid in Hingham. Worked 6 hours for Henrietta — helping Frank take down building — 1.00. Cloudy; W.S. and S. Began to rain (light) about 2:30 P.M. Had supper there and came home in eve. Walked to Hingham Sta. (1 1/4 miles) and came on 7 P.M. tr. began to rain again when I was about half way to H. Sta. rain all eve. W.S.W. warm. — tem. 52. Played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours in eve. 12 (mid) still raining.

30th. (Sun.) Clear. Warm. W.W. to N.W. tem. 50-66. Very windy – gale 36 m. Eve. clear. Cold. W.N.W. Staid at home to-day.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original. The catalog record for the George Hyland’s diary may be found here. Hyland’s diary came to us as part of a collection of records related to Hingham, Massachusetts, the catalog record for this larger collection may be found here.