By Lauren Duval, NEH-MHS Long-term Research Fellow, Assistant Professor of History, University of Oklahoma

This past fall I was delighted to spend time at the Massachusetts Historical Society as a research fellow. Analyzing British-occupied cities during the American Revolution, my research centers the urban household and examines how civilian families navigated the disruption of occupation and the consequence of this experience, both during and after the war. The voluminous correspondence of the loyalist Murray family proved an exceptional source for examining these dynamics, offering a fascinating glimpse into how one Boston family navigated the hardships of martial law during the early months of the war.

On April 20, 1775, in the wake of the battles at Lexington and Concord, Bostonians awoke to startling news that they were, in the words of one woman, “Genl. Gage’s prisoner[s]—all egress, & regress being cut off between the town & country.”[1] In the months that followed, both the British army and the militia (later Continental army) besieging Boston were hesitant to allow civilians to cross military lines, fearing disease, espionage, and the loss of resources. Some fortunate Bostonians managed to secure passes.[2] Many others, however, lingered in the besieged city (whether by choice or circumstance), where they endured food shortages, disease, plunder, and violence, and struggled to communicate with friends and family outside the British garrison.

The Murray family was stranded on both sides of the lines. Residing in Boston alongside his wife, Elizabeth, and youngest daughter Betsy, loyalist James Murray occupied his time by gardening and reading books, the latter of which he jokingly referred to as “the best friends now left to me.”[3] His sister, Elizabeth Murray Campbell Smith Inman and eldest daughter, Dolly Murray Forbes dwelt at the family’s Brush-hill estate, in Cambridge, surrounded by Continental troops. Later in the occupation, Betsy, to her parents’ distress, would abandon the garrison to shelter at Brush-hill.[4] Crossing the lines was nevertheless a fraught endeavor, even with permission. In the fall of 1775, for instance, Elizabeth Inman was advised to remove into the garrison for safety. She obtained a pass to visit Boston and became stranded there for the remainder of the occupation.[5]

Despite being separated by only a few miles, the Murray family was divided by both wartime circumstances and military boundaries. Obtaining passes from commanding officers, they arranged meetings at the military outposts that separated the British garrison at Boston from the Continental camp in Cambridge. Such conferences permitted them to visit, exchange news, and offer reassurances of safety. But they were far from private. As James Murray explained in July 1776, a British officer would observe the family’s gatherings “to be Eye & Ear Witness of all that passes.” This precaution, Murray explained, was for the family’s protection and he strongly advised “the Ladies . . . to use the same precaution, on their side: the Times require it.”[6] With various family members stranded on either side of the lines, dependent upon the protection of both armies, the Murrays could ill-afford to be charged with treasonous behavior by either faction. Witnesses, both British and Continental, who could attest, if necessary, to the content of the family’s conversation was an important shield against such charges. Still, the Murrays were cautious not to meet too frequently, fearful of raising suspicions among Massachusetts revolutionaries.[7]

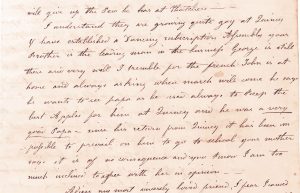

Like inhabitants of occupied cities throughout British North America, the Murrays struggled with the lack of private communications. They lamented the necessity of leaving letters unsealed for inspection and bemoaned the uncertainty of conveyance. The Murrays, with their regular visits at the lines, were in some ways, more fortunate than those families who had to settle for letters or word-of-mouth reassurances of safety. When possible, the Murrays used private channels, entrusting their missives to neighbors who had obtained passes to cross the lines. Such conveyances were nevertheless circumspect; nothing of consequence could be committed to paper, lest the letter be intercepted.[8] Occasionally, the Murrays sent letters and goods via servants and enslaved messengers, whose roles as laborers permitted them to more easily traverse military lines.[9] Such mobility could, however, be perilous. Enslaved laborers were routinely plundered and kidnapped. Disease flourished near military encampments. Like white civilians, the enslaved could become trapped within the garrison, far from their own families and where they encountered far more difficulties in learning about their loved ones’ well-being. Proximity to the British army nevertheless offered a chance for freedom, and approximately twenty thousand self-emancipated men, women, and children made their way to the British lines during the war.[10]

Despite scrupulous planning, miscarried letters, delayed passes, and other mishaps disrupted the Murrays’ meetings.[11] Weather could deter visits, especially in the frigid winter months.[12] Wartime circumstances introduced additional fears; in the midst of civil war, surrounded by two armies, safety was no guarantee. Hinting at the strain of nine-months-long separation, in January 1776, James Murray wrote to his daughters, requesting them to “bring with you as healthy & chearful Countenances as you did at our last [meeting].” “Your very looks will be a feast to your old Father tho not a Word pass,” he assured them.[13] But even as such glimpses fortified the family for the hardship ahead, the long period of separation exacerbated other worries. Parted from his grandsons for several months, James Murray and his wife Elizabeth worried that “they will have quite forgot us.”[14] Each time the family sent off a letter, they worried, as Dolly expressed to her father in May 1775, that “it may be the last time we can hear from you.”[15]

Although only one facet of the wartime disruption that Bostonians faced in the early years of the war, the experiences of the Murray family underscore the deeply personal and intimate ways in which the war affected American families. Residing between two armies, the challenges that the family faced speak not only to the hardship that civil war inflicted on civilians residing in and around the Boston garrison, but also illustrate in vivid detail the consequences of these circumstances on daily life and familial relationships. As Dolly Forbes feared, the separation from her parents did become permanent. Like many Boston loyalists, James and Elizabeth Murray evacuated Boston with the army in March 1776. They eventually settled in Halifax, where James died in 1781, far from the family that he had valiantly struggled to keep unified during the war.[16]

[1] Sarah Winslow Deming Journal, April 20, 1775.

[2] Permit to pass through British lines, May 1775, Miscellaneous Bound Manuscripts, 1774–1775.

[3] James Murray to Dorothy Forbes & Betsey Murray, October 2, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2 (garden); James Murray to Elizabeth Inman, May 23, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2 (quotation).

[4] James Murray to Dorothy Forbes & Betsey Murray, October 2, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[5] Memorial of Dorothy Forbes of Milton to the Honble. Council & House of Representatives of the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay, December 12, 1775, Murray Robbins Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 4.

[6] James Murray to Elizabeth Inman and Dolly Forbes, July 26, 1775, Murray Robbins Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 4.

[7] James Murray to Dorothy Forbes & Betsy Murray, Feb 10, 1776 (James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[8] James Murray to Dorothy Forbes and Betsy Murray, November 6, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[9] For a few examples, see James Murray to Elizabeth Inman, May 17, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2; James Murray to Elizabeth Inman, Boston, Thursday, May 18, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2; Elizabeth Inman to Ralph Inman, 29th & 30th May 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2; Elizabeth Inman to Dorothy Forbes and Betsy Murray, October 28, 1776, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[10] Cassandra Pybus, “Jefferson’s Faulty Math: The Question of Slave Defections in the American Revolution,” The William and Mary Quarterly 62, no. 2 (2005): 261.

[11] Letter to Betsie Murray, February 23, 1776, Murray Robbins Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 5, (miscarried); Elizabeth Inman to Ralph Inman, Sunday April 30, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2 (delayed).

[12] James Murray to Dolly Forbes and Betsy Murray, February 14, 1776, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[13] James Murray to Dorothy Forbes & Betsy Murray, January 10, 1776, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[14] James Murray to Dorothy Forbes and Betsy Murray, November 6, 1775, James M. Robbins Family Papers, Box 2.

[15] Letters of James Murray, Loyalist, ed. Nina Moore Tiffany and Susan Inches Lesley (Boston, 1901), 199.

[16] James Henry Stark, The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution (J.H. Stark, 1907), 258–60.