By Rakashi Chand, Senior Library Assistant

MHS library staff members answer reference questions from far and near through e-mail, chat, mail, social media, and by phone on a daily basis. While working on one such reference question, I needed to consult a box from the Ellery Sedgwick papers. Sedgwick was the Editor of America’s most noteworthy literary magazine in the early 20th century, the Atlantic Monthly. As I read through the names of correspondents in the collection guide, one name jumped out at me. This was a name that I know well but never thought I would see at the MHS: Rabindranath Tagore. ‘Could this be?’ I thought to myself. As an Indian-American raised in the United States, I have always admired Tagore so I was astounded by this serendipitous discovery.

Ranidranath Tagore was and is India’s literary giant. Tagore was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 1913, the first non-European to be awarded a Nobel Prize, in any category. Tagore was knighted by King George V in 1915. He renounced the knighthood in 1919 in response to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre when British troops gunned down hundreds of innocent Indians. A supreme hyphenate, Tagore was a poet, writer, spiritualist, and artist, and he wrote the Indian national anthem. Tagore helped define the culture of modern India. He represented India in his travels and lectures around the world, not as a British colony, but as a unique country with a long history, rich culture, and a diverse people. Cumulatively, Tagore spent the greatest amount of time outside of India in the United States over a series of three trips.

I eagerly awaited the arrival of the offsite box and was filled with elation when it arrived. The letters, five in total, plus one from his private secretary, span the years 1914 to 1930.

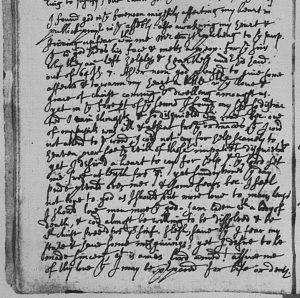

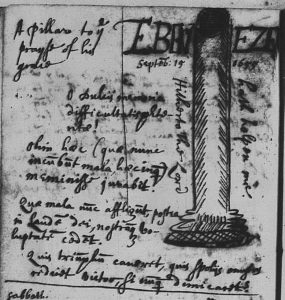

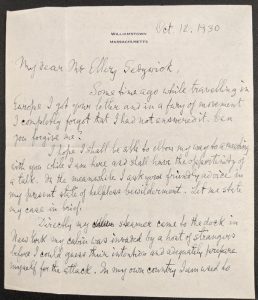

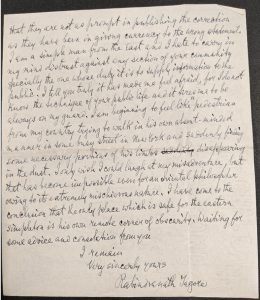

Most of the letters discuss submissions to be published in the Atlantic Monthly. One letter dated 12 October 1930 was very unusual and intriguing. In it Tagore writes to Sedgwick as a friend seeking guidance on how to handle the American media. In this letter, Tagore reveals his thoughts not only about his experience of coming to America, but what he feels as an Indian in America at that moment in time trying the grasp and understand American culture. The letter is magnificent in depth, intimacy, and detail. Please see below for an unofficial transcription. The letterhead is of Williamstown, Mass. where Tagore would have been staying at the time.

Williamstown

Massachusetts Oct. 12, 1930

My Dear Mr. Ellery Sedgwick,

Some time ago while travelling in Europe I got your letter and in a fury of movement I completely forgot that I had not answered it. Can you forgive me?

I hope I shall be able to elbow my way to a meeting with you while I am here and shall have the opportunity of a talk. In the meanwhile I ask your friendly advice in my present state of helpless bewilderment. Let me state my case in brief.

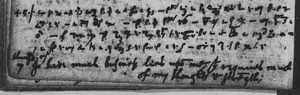

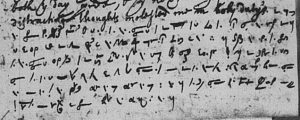

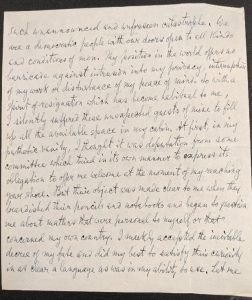

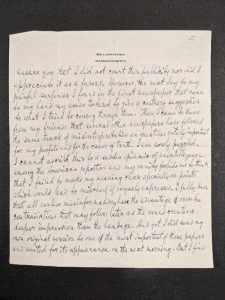

Directly my steamer came to the dock in New York, my cabin was invaded by a host of strangers before I could guess their intention and adequately prepare myself for the attack. In my own country I am used to such unannounced and unforeseen catastrophe. We are a democratic people with our doors open to all kinds and conditions of men. My position in the world offers no barricade against intrusion into my privacy, interruption of my work or disturbance of my peace of mind. So with a spirit of resignation which has become habitual to me, I silently suffered these unexpected guests of mine to fill up all of the available space in my cabin. At first, in my pathetic vanity, I though it was deputation from some committee which tried in its own manner to express its obligation to offer me welcome at the moment of my reaching your shore. But their object was made clear to me when they brandished their pencils and notebooks and began to question me about matters that were personal to myself or that concerned my own country. I meekly accepted the inevitable decree of my fate and did my best to satisfy their curiosity in as clear a language as was in my ability to use. Let me assure you that I did not court this publicity nor did I appreciate it as a favour. However, the next day to my painful surprise I found in the first newspaper that came to my hands my words twisted to give a contrary suggestion to what I tried to convey to them. Then I came to know from my friends that several other newspapers have followed the same track of misinterpretation on questions vitally important for my people and for the cause of truth. I am sorely puzzled. I cannot ascribe this to a sudden epidemic of unintelligence among the American reporters and my vanity forbids me to think that I failed to make my meaning clear specially on points which would lead to mischief if vaguely expressed. I fully know that all earlier misinformations have the advantage over the contradictions that follow later as the wound creates a deeper impression than the bandage. And yet I did send my own original version to one of the most important of these papers and waited for its appearance on the next morning. But I find that they are not as prompt in publishing the correction as they have been in giving currency to the wrong statement. I am a simple man from the East and I hate to carry in my mind distrust against any section of your community specially the one whose duty it is to supply information to the public. I tell you truly it has made me feel afraid, for I do not know the technique of your public life and it tires me to be always on my guard. I am beginning to feel like a pedestrian from my country trying to walk in his own absent-minded manner in some busy street in New York and suddenly finding some necessary portions of his limbs disappearing in the dust. I only wish I could laugh at my misadventure, but that has become impossible even for an oriental philosopher owing to its extremely mischievous nature. I have come to the conclusion that the only place which is safe for the eastern simpleton is his own remote corner of obscurity. Waiting for some advice and consolation from you

I remain

Very sincerely yours

Rabindranath Tagore

Sent from:

Buxton Hill

Williamstown

Massachusetts

This poetic letter reveals so much about Tagore and his experience in America and with the American public. Tagore embarked on his journeys to connect with to learn as much as possible about people across the globe, while also sharing the wealth of culture, philosophy, ideology and art from his own country, a country fighting for freedom against colonial oppression.

This letter and so much more can be found at the MHS. Please reach out for more information about visiting the library. For further reading on collections held at the Society related to the history of India, please see our blog post Boston to Bombay*: Historical Connections between Massachusetts and India | Beehive (masshist.org).