By Gwen Fries, The Adams Papers

Every January we’re bombarded with advertisements for the sneakers, the stationary bike, or the protein shake that’s going to transform our lives. The strange New Year’s cocktail of hope and shame leads many to splurge on workout gear and gym memberships only to abandon them a week or two later. If that’s you, you’re in good company. In 1756 John Adams admitted to his diary, “I am constantly forming, but never executing good resolutions.”

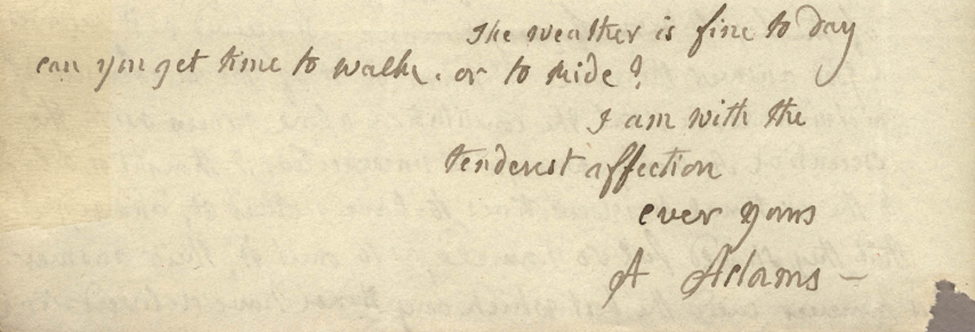

May I suggest you look to the Adamses rather than advertising executives as you plan your 2023? The Adamses were concerned with their health too, but they took a simpler, more attainable approach that didn’t cost a dime. John Adams wrote.

“Neither medicine nor diet nor any thing would ever succeed with me, without exercise in open air: and although riding in a carriage, has been found of some use, and on horseback still more; yet none of these have been found effectual with me in the last resort, but walking.”

Over the years John and Abigail Adams suggested walking as a cure for headaches, stomachaches, weight gain, weight loss, anxious hearts, tired eyes, overwork, and the winter blues.

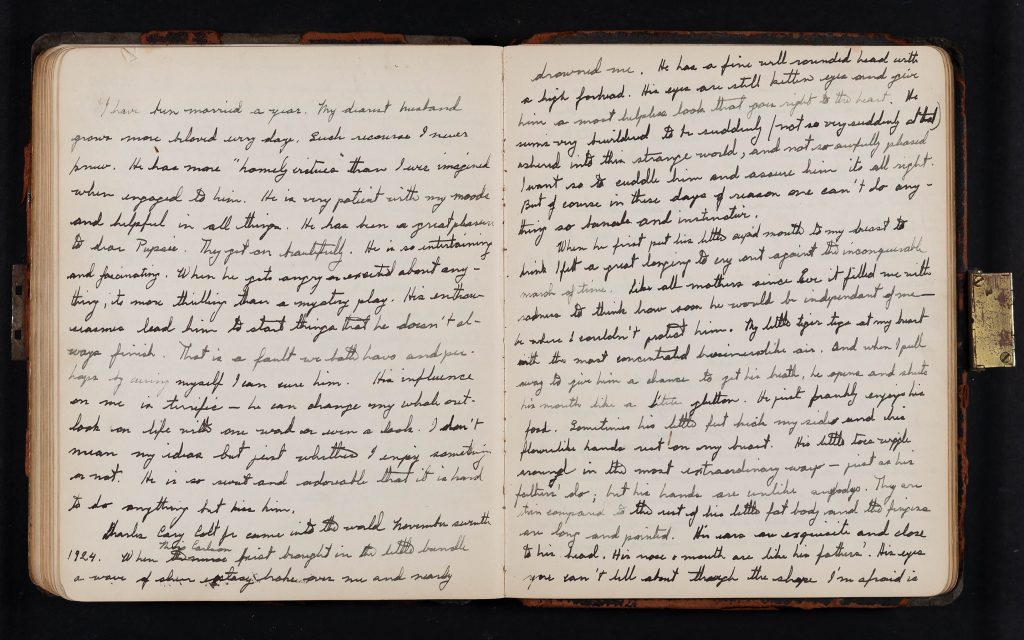

“Our Bodies are framed of such materials as to require constant exercise to keep them in repair, to Brace the Nerves and give vigor to the Animal functions. thus do I give you Line upon Line, & precept upon precept,” Abigail wrote to her son John Quincy in 1787. “A Sedantary Life will infallibly destroy your Health,” she cautioned her eldest son, “and then it will be of little avail that you have trim’d the midnight Lamp. In the cultivation of the mind care should be taken, not to neglect or injure the body upon which the vigor of the mind greatly depends.”

Walking on a treadmill will benefit the body, but a walk in the fresh air will benefit the soul. “Exercise and the Air and smell of salt Water is wholesome,” John Adams wrote in his diary. “Take your fresh Air, and active Exercise regularly,” he encouraged his son. Even in the middle of winter, walking outside can bolster the spirit. “Cold clear Air” had the ability to give “a Spring to the System,” Adams believed.

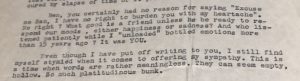

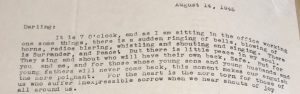

Whatever you choose to do this year, be gentle with yourself. Let the tender advice John Adams gave his son serve you as well:

“Take care of your Health. The smell of a Midnight lamp is very unwholesome. Never defraud yourself of your sleep, nor of your Walk. You need not now be in a hurry.”

You’ve got all of 2023 before you. You need not be in a hurry.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.

![Comical drawing of a man with mustache and receding hairline, whose breeches extend up to his neckline. He holds a top hat in his left hand, a riding crop[?] in his left. Not signed.](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Freds-breeches-225x300.jpg)