By Neal Millikan, Series Editor, Digital Editions, The Adams Papers, MHS

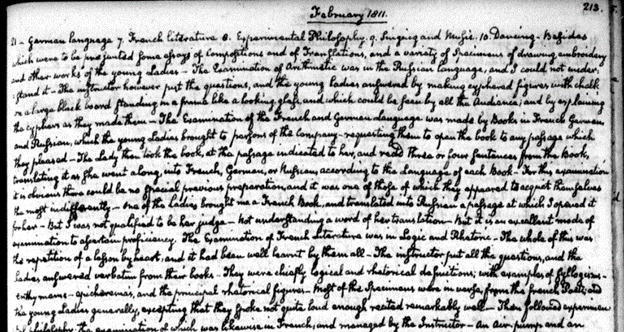

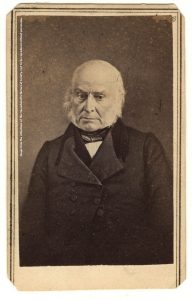

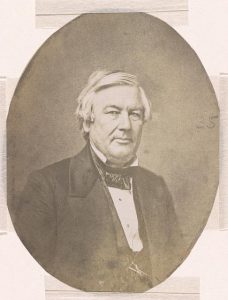

The Adams Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society has been editing the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary since 2016. Adams kept his diary for 68 years, starting when he was twelve and continuing until his death. In total it comprised 51 diary volumes and over 15,000 pages. As you can imagine, his diary mentioned lots of people: some famous and some obscure. As we have been transcribing the diary for digital publication, we have also been identifying and tagging individuals at their first mention within each date entry. Millard Fillmore and Zachary Taylor both appeared in the diary; we have tagged Fillmore’s name 211 times and Taylor’s name 20 times. In this post I want to highlight some of the mentions of Fillmore, all of which occurred after Adams’s (1825–1829) and before Fillmore’s (1850–1853) presidencies and focus on their years serving together in the U.S. House. This blog pairs nicely with a recent post on Fillmore, Taylor, and Congress.

Apart from the fact that both men served as president, Adams and Fillmore had some other things in common: they were both Unitarians, both members of the Whig party (after each had briefly flirted with the Anti-Masonic party), and both represented northern states in Congress (Adams Massachusetts, Fillmore New York). While there was an age gap between the two congressmen—Fillmore was born about the same time as Adams’s eldest son (George Washington Adams, 1801–1829)—they served together in the U.S. House during the 23d, 25th, 26th, and 27th congressional sessions.

Fillmore first showed up in Adams’s diary on 7 December 1833, where Adams recorded his first name as “Mellerd” in the list of individuals with whom he visited on that date. This was not unusual, as Adams often wrote a name one way (how he believed it was spelled) and then adjusted his spelling in later diary entries. Interestingly, while he started spelling Fillmore’s first name correctly, Adams used the spellings of “Fillmore” and “Filmore” interchangeably. Beginning in January 1834, Fillmore routinely appeared in the diary as Adams reported on congressional activities.

The next significant mention of Fillmore was on 25 December 1837 when Adams noted that he, along with three other representatives from New York (Richard Marvin, Charles Mitchell, and Luther Peck), “came and requested me to draw up a paper to address to their Constituents assigning their reasons for voting against the resolution for laying all abolition petitions on the table.— They said they wished to guard against the amputation of favouring abolitionism, but to adhere inflexibly to the right of Petition,” one of Adams’s pet congressional causes, as he waged his years’ long fight against the gag rule. “I drew up accordingly a sketch of an address to the People of the State of New-York—according to their ideas.” Adams gave the document to Fillmore on 26 December.

Over the next several years Fillmore is consistently mentioned in the diary. Adams noted that he, like other representatives, championed the causes and concerns of his constituency in the U.S. House. On 12 March 1838, Fillmore “presented a Memorial from a meeting of Inhabitants of his District, where the capture of the Steam boat Caroline took place, complaining of that act, and praying for defensive military force.” This memorial was about the Caroline affair, an international incident during which an American vessel was destroyed by Canadian militia in December 1837.

Adams was critical of Fillmore’s attitude toward the Seneca Nation of New York, stating his belief on 23 May 1838 that Fillmore “had by some unnatural influence been induced to assume the defence of Schermerhorn’s swindling practices.” This comment related to John Schermerhorn’s part in the 1832 Treaty with the Seneca and Shawnee Nations. The following day his diary entry compared Fillmore to James Graham, a North Carolina representative who supported Cherokee removal from that state. According to Adams, while Fillmore and Graham’s “judgment and feelings” were “fair, just and humane in all cases which touch not the immediate interests and passions of their Constituents,” they were “unseated when Cherokee or Seneca Indians are parties concerned in the question.”

Not all the references to Fillmore dealt with political issues; he is mentioned in the diary for other reasons as well. For example, on 18 May 1838, Adams recounted that he returned a book to the Library of Congress—an English edition of Father Louis Hennepin’s Description de la Louisiane—because Fillmore had requested to check it out. By the 1840s, the two men were on friendly terms with each other. When Adams visited Niagara Falls in July 1843, now former congressman Fillmore invited him to also tour Buffalo, New York, while he was in that state. When Adams arrived in Buffalo on the 26th, Fillmore introduced him to a gathered crowd, and the two men then rode around the city together. When Adams again visited Buffalo that October, Fillmore “invited us to tea at his house . . . and offered us seats in his pew at the unitarian church,” both of which the former president accepted. Adams’s last mention of the future president was on 20 August 1847, when Fillmore visited Boston and they had dinner together. Adams died on 23 February 1848, so he did not live to see Fillmore’s presidency.

One of the interesting aspects of the work of documentary editing is analyzing primary sources like Adams’s diary and learning that the sixth and thirteenth presidents were well acquainted with each other. From Adams’s diary and from Fillmore’s letters, we get a sense of how the lives of these two presidents intertwined in the nineteenth century.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund, with additional contributions by Harvard University Press and a number of private donors. The Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Historical Publications and Records Commission also supports the project through funding for the Society’s Primary Source Cooperative.

Postscript: Millard Fillmore on John Quincy Adams

By Michael David Cohen, Editor and Project Director, The Correspondence of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore, American University

Millard Fillmore’s relationship with John Quincy Adams continued after their time together in Congress. The Correspondence of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore, at American University’s Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies, has been locating and editing Taylor’s and Fillmore’s letters since 2020. Our forthcoming edition is more temporally constrained than the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary. We are preparing a three-volume, print and digital edition of letters that the two men wrote or received between 1844 and 1853. That decade began with General Taylor’s preparing to lead U.S. troops into the Republic of Texas, continued through the Mexican-American War, and concluded with Taylor’s and Fillmore’s presidencies. Taylor entered the White House in 1849 but died in 1850; Fillmore, his vice president, completed the term.

During those years, until his death in 1848, Adams continued to serve in the U.S. House. Not surprisingly, his fellow Whig and former House colleague Fillmore exchanged occasional letters with or about him. But let’s start with Taylor.

Although Taylor ran for president as the Whig Party’s nominee in 1848, he had never served in civil office before and often foreswore any partisan identity. He may never have voted. Before his candidacy he corresponded with a few national politicians, including Senators John J. Crittenden (a Whig) and Jefferson Davis (a Democrat and his son-in-law), but not with many. Of the more than 1,300 letters our project has found by or to Taylor between 1844 and Adams’s death, none was exchanged with Adams. Only one mentioned him.

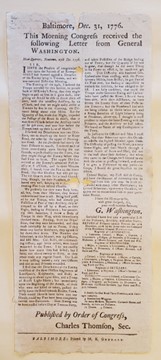

Taylor’s single reference to Adams came in a letter of August 10, 1847, to F. S. Bronson. Answering Bronson’s request for “my views on the questions of national policy now at issue,” Taylor denied being a presidential candidate and mostly refused to disclose his opinions. But he did repeat Bronson’s praise for a list of Whig and Democratic politicians. As amended by the Washington Daily National Intelligencer, which published the letter on October 5, Taylor shared “your high and just estimate of the virtues, both of head and heart, of the distinguished citizens [Messrs. Clay, Webster, Adams, McDuffie, and Calhoun] mentioned in your letter.” So, apparently, he respected Adams.

Adams showed up a bit more often in Fillmore’s correspondence. Of nearly 1,000 letters between 1844 and Adams’s death, four involved Adams or his close family. On June 5, 1844, the Washington, D.C., artist Elizabeth Milligan wrote to Fillmore about her recent work. Reflecting on her experience painting Dolley Madison, she remarked that the former White House hostess “and J. Q. Adams seem to be the links that connect ours with a past age” (SUNY-Oswego/Millard Fillmore Papers). A year later Fillmore received a letter from Charles Francis Adams, John Quincy Adams’s son, reporting a Massachusetts convention’s opposition to the annexation of Texas. (We published that letter last year as part of our teaching guide on Texas annexation.)

The remaining letters came near the end of Adams’s life. On February 10, 1848, Fillmore wrote to Adams himself—the letter is now preserved in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s Adams Papers—to introduce a friend “to the ‘Old Man Eloquent.’” Fillmore expressed pleasure that Adams continued to serve in Congress “in this great national crisis.” Thirteen days later, Representative Nathan K. Hall informed his friend Fillmore that “Mr Adams cannot survive many hours” (SUNY-Oswego/Fillmore Papers). Indeed, having suffered a stroke on the House floor, John Quincy Adams died that day.

Fillmore and Adams’s relationship ended with the latter’s death. Fillmore, Taylor, and others were left to carry on the brief political career of the Whig Party. We at the Taylor-Fillmore project are proud to be contributing, along with the Adams Papers, to expanding access to primary sources from both prominent and obscure individuals in that pivotal era of U.S. history.

The Taylor-Fillmore project at American University thanks the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) and The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, our current sponsors. We also thank our past contributors: Delaplaine Foundation Inc., the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, the Summerlee Foundation, and the Watson-Brown Foundation. The Mellon Foundation in partnership with the NHPRC supports our project through funding for the University of Virginia Digital Publishing Cooperative.