By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

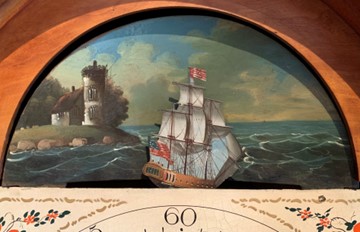

I’m happy to report that the records of the Algonquin Club of Boston have been processed and are now available for research. The Algonquin Club was a social club founded in 1886 “for the purpose of maintaining a club house and reading room in the city of Boston.” For most of its existence, the club was located at 217 Commonwealth Avenue, a beautiful Renaissance Revival limestone building in Back Bay designed specifically for the club by noted architects McKim, Mead & White in 1888.

The club served as a gathering place for members (originally only men), including politicians, businessmen, lawyers, judges, financiers, academics, ambassadors, and other movers and shakers in Boston and surrounding towns. The name of the club appears in countless “who’s who” biographies. Prospective members were nominated by existing members, subjected to a vetting process, and approved by the Executive Committee.

The clubhouse offered a number of amenities. Members could play cards or pool; smoke cigars or pipes; read in the library; enjoy a meal in one of several restaurants; attend a talk, party, or other event; and even reserve a bedroom for an overnight stay. Members also had the benefit of reciprocal relationships with similar clubs in other cities and countries.

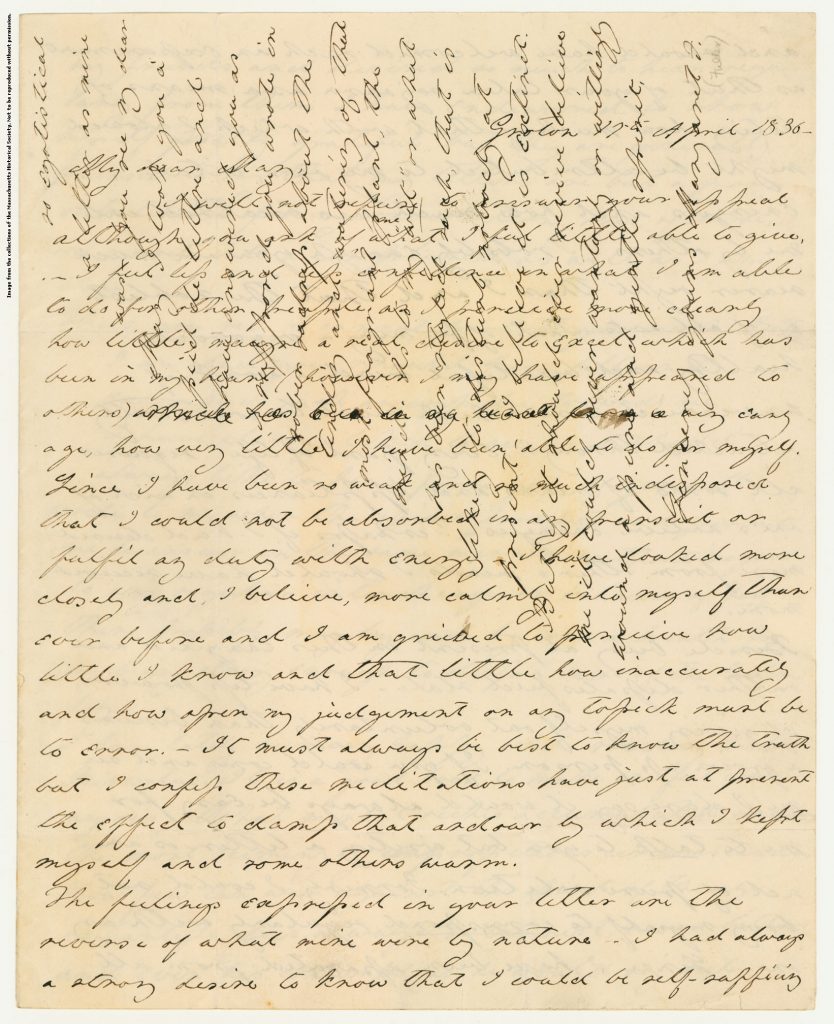

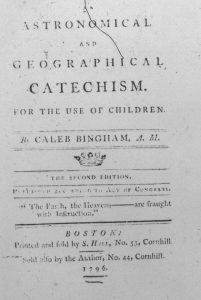

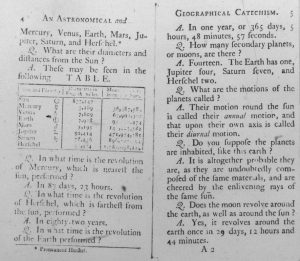

The Algonquin Club records contain a small amount of older material documenting the club’s early years, such as a book with the signatures of original members, a volume of Executive Committee meeting minutes from 1898 to 1927, a visitors register kept from 1917 to 1921, and a time capsule compiled in 1936 and opened for the club’s centennial in 1986.

Unfortunately there’s a gap in the collection through the middle of the 20th century; most of the extant papers date from about the 1980s to the 2000s. That being said, the collection is a great resource for anyone researching elite Boston clubs, as well as other subjects. For example, foodies might enjoy the specially designed dinner menus printed for club events. And anyone interested in the building itself should appreciate the oversize architectural plans and details.

Processing this collection proved challenging for a few reasons. The first was the sheer size of it. The final collection measures approximately 46 linear feet, and that’s only after I weeded out eight cartons of duplicate documents. The bulk consists of 63 manuscript boxes containing almost 3,000 member files. That’s 3,000 individual folders that needed alphabetization, weeding, refoldering, and labeling by hand. (Because of privacy concerns, these member files have been closed until the year 2041.)

Secondly, the papers came to us with about 70 pieces of digital media, both 3.5 inch floppy disks and CDs. These media and the files they contained—files in a variety of formats, many obsolete—needed to be assessed by the Digital Processing Archivist, reformatted as necessary, then incorporated by me into the arrangement and description of the collection.

It’s not news to any of the archivists out there that repositories are acquiring more and more “born digital” records alongside (or even independent of) paper documents. Just think of your own files: you probably have texts, emails, Word documents, spreadsheets, digital photographs, videos, etc., not to mention social media content. Many files probably exist only in the cloud, but others may be on hard drives or backup drives.

In the fall of 2021, the MHS purchased the digital preservation system Preservica, and the digital preservation team has been developing policies and procedures for ingesting, processing, preserving, and providing access to these records. Each collection will probably require its own unique approach, but when Preservica goes live (eta: spring 2024), researchers will be able to link to digital material directly from a collection guide.

Keep an eye out for Preservica!

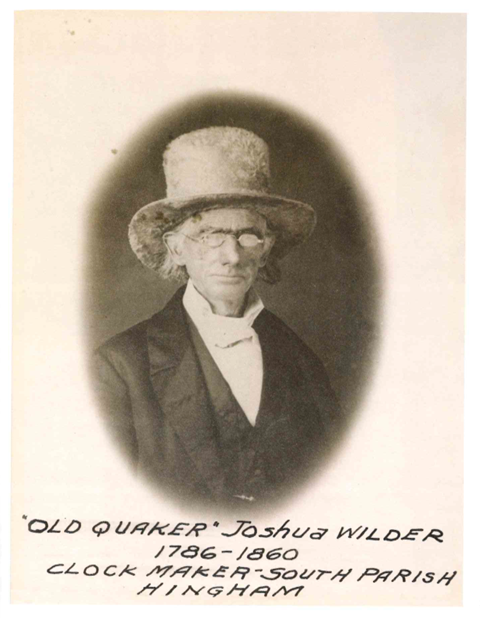

The MHS also holds the Algonquin Club of Boston photographs.