By Blake McGready, The Graduate Center, CUNY

Elijah Winslow disobeyed his sergeant’s orders and went swimming in the Susquehanna River, so he had no one to blame but himself when he drowned. In the summer of 1779, Winslow and thousands of other Continental soldiers assembled in the Pocono Mountains as they prepared to invade the homelands of the Haudenosaunee people. While encamped at Easton, Wyoming, and other mountain villages, American revolutionaries flagrantly defied orders. They deserted camp, plundered the locals, and indulged in swimming in the rivers. Winslow was one such offender. A sergeant remembered that “Winslow asked Leave…Repeatedly both Last Night and this Morning to Go into the River.” After the sergeant denied Winslow’s request, he ventured into the water anyway. By the end of the day, the army determined that Winslow’s death was “entirely Accidental.”[1]

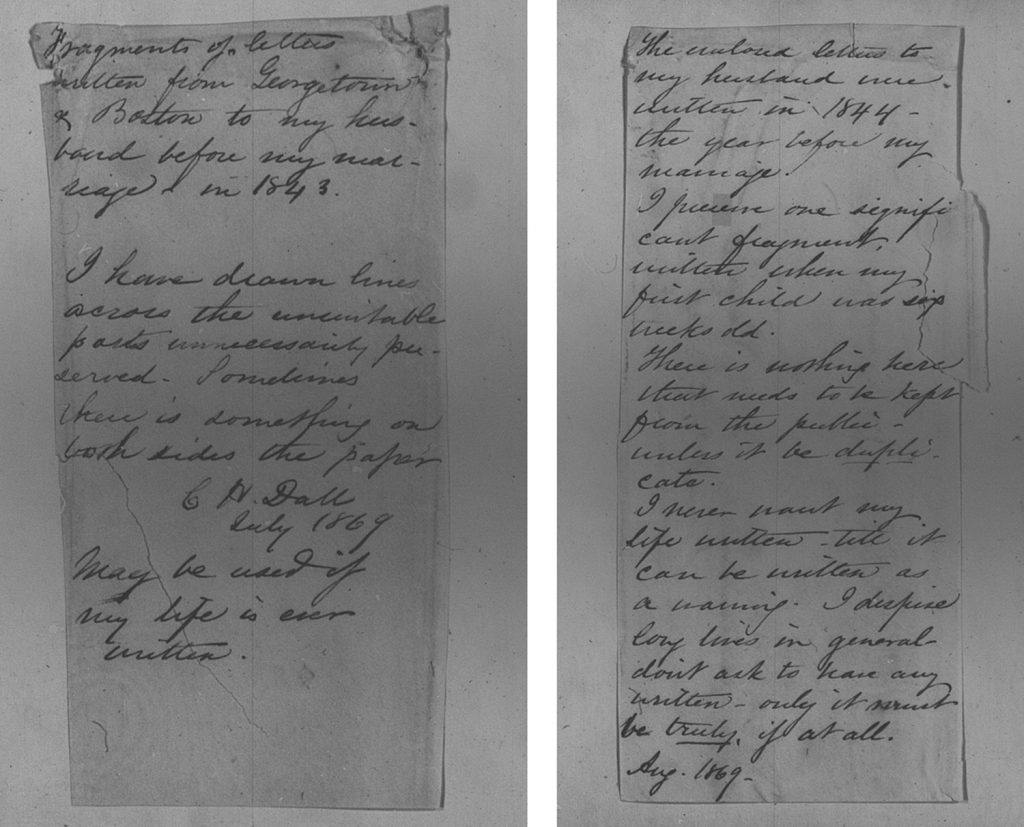

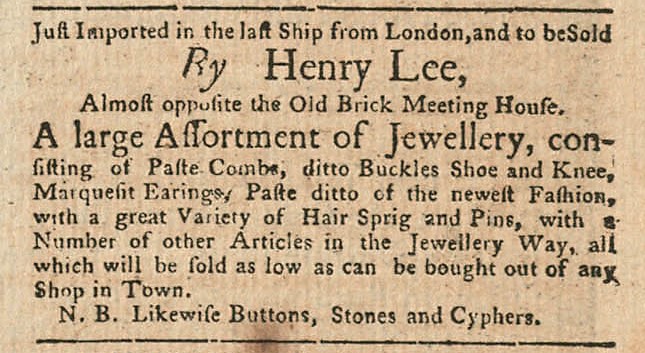

I read this account in the orderly book of the 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, one of the many Revolutionary War orderly books at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Orderly books document everyday details about life in the Continental Army—the officers in charge, the placement of troops, accounts of battlefield defeats and losses, etc. For a scholar looking more closely, these records also show enlisted men struggling with officers over the conditions of their service. Officers wanted to secure the compliance of unruly troops, while at the same time rank and file soldiers objected to military hierarchy. Orderly books seethe with conflict between officers and their disobedient men.[2]

The 2nd New Hampshire Regiment’s insubordination leaps off the pages. When the army arrived at Easton, officers ordered soldiers to limit their bathing in the nearby Delaware River. Less than a week later, officers repeated the prohibition, now reporting that some soldiers developed “Intermitting Fevers” on account of their “their too frequent Going into the Water and Remaining too Long in that Situation.” Despite repeated orders against swimming, Elijah Winslow drowned one month later.[3]

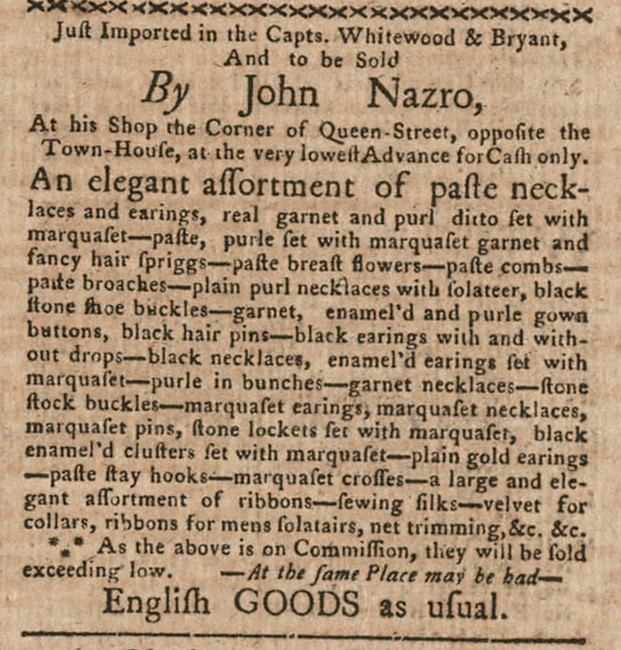

Theft was another major issue. When Yankee soldiers arrived at Easton, several of them harassed and plundered the town’s mostly German inhabitants. After Continentals traveled “a Great Distance…into the Country” and robbed the locals, commanders established a half-mile perimeter around camp. The restrictions did not work, and soldiers were soon caught stealing sheep from local farmers. A court martial also found several New Jersey soldiers guilty of “Stealing hoggs” and other property from civilians. In early July, Major General John Sullivan begged his men to not rob the locals’ hay or burn their fences.[4]

Sullivan struggled to stop vengeful troops from taking matters into their own hands. Armed parties departed camp and intimidated disaffected locals. Continentals insulted Native allies (“Warriers of the Anydas [Oneidas] Tuscorara and Stock bridge Indians”) who had recently joined the rebel ranks. How dare soldiers “Ridicule & Speak Contemtably” of the Native troops, Sullivan declared. But over the coming days, the jeering continued and tensions between white revolutionaries and Native soldiers simmered.[5]

In August and September, the Continental Army ferociously devastated Iroquoia. As the maelstrom of Continental predation barreled through the Haudenosaunee heartlands, soldiers burned Native villages, assaulted Native women, and robbed Native gravesites. What can an orderly book tell us about this pivotal invasion? During the weeks before the army entered Iroquoia, officers had been struggling constantly with their troops’ discipline. Soldiers repeatedly violated orders against bathing, stealing, and taunting Native soldiers. The Continentals, it seemed, were spoiling for a fight.[6]

As American revolutionaries destroyed Haudenosaunee villages and farms, they wrote many journals and diaries bragging about the devastation. Their orderly books, however, tell a different story. These documents shed light on soldiers’ numerous infractions and the tensions within the Continental Army. Furthermore, they reveal that soldiers’ acts of plundering and terror began well before the army stormed into Iroquoia. In the Poconos, the Continentals rehearsed the destruction and belligerence that would characterize their invasion of Native lands.

[1] “Winslow askd Leave…,” entry dated July 6, 1779, Orderly book, Wyoming and Easton, Pennsylvania, 27 May-25 July 1779, 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, Continental Army, recorded by William Mordaunt Bell, Revolutionary War Orderly Books (P-394), Reel 4, Massachusetts Historical Society. (I have modernized the spelling of most entries but included the original text in the notes.)

[2] John A. Ruddiman, “‘A Record in the Hands of Thousands’: Power and Negotiation in the Orderly Books of the Continental Army,” The William and Mary Quarterly 67, no. 4 (2010): 748.

[3] Entry dated May 29; “Intermitting Fevors”; “their two [sic] frequent Going into the Water and Remaining two Long in that Situation,” entry dated June 9.

[4] Liam Riordan, Many Identities, One Nation: The Revolution and Its Legacy in the Mid-Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 80; “a Great Distance…into the Cuntrey,” entry dated June 7; entries dated June 9, 24, July 5, 12.

[5] Entries dated June 10, 15, 24.

[6] For actions of Sullivan’s men in Iroquoia, see Maeve Kane, “‘She Did Not Open Her Mouth Further’: Haudenosaunee Women as Military and Political Targets during and after the American Revolution,” in Women in the American Revolution: Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World, ed. Barbara B. Oberg (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 83–92.