by Elizabeth Hines, 2024-5 NERFC Fellow

When is it the right time to make war on one’s neighbor? The colonies in New England and New Netherland debated this question in the early days of European expansion, just as countries do today. The Massachusetts Historical Society’s collection contains material that sheds light on a little-known almost-war between neighbors on North America’s shores: the time New England’s planned attack on New Netherland was cancelled by news of a peace treaty. The MHS is one of the most important archives historians can use to trace this dramatic story.

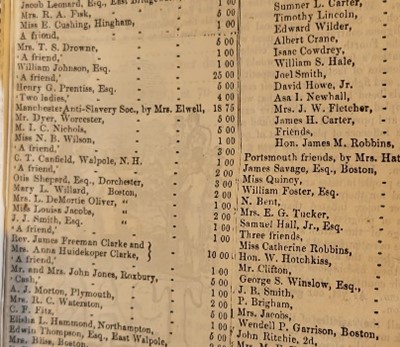

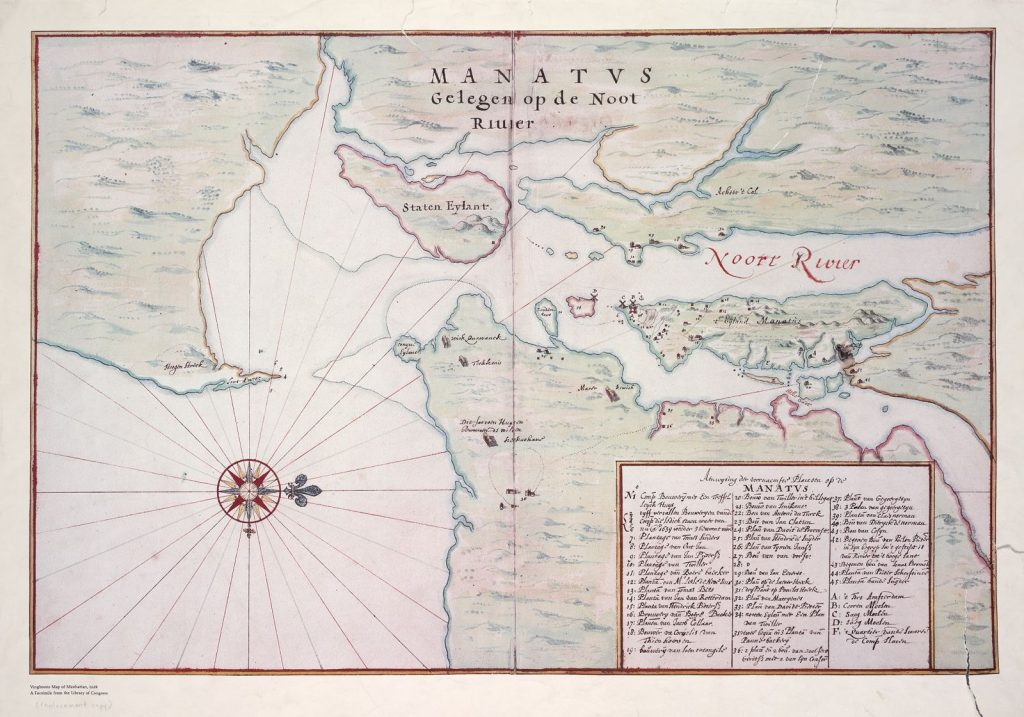

The Dutch colony of New Netherland was located to the east and south of the New England colonies, in what is now New York.

From the New York Public Library

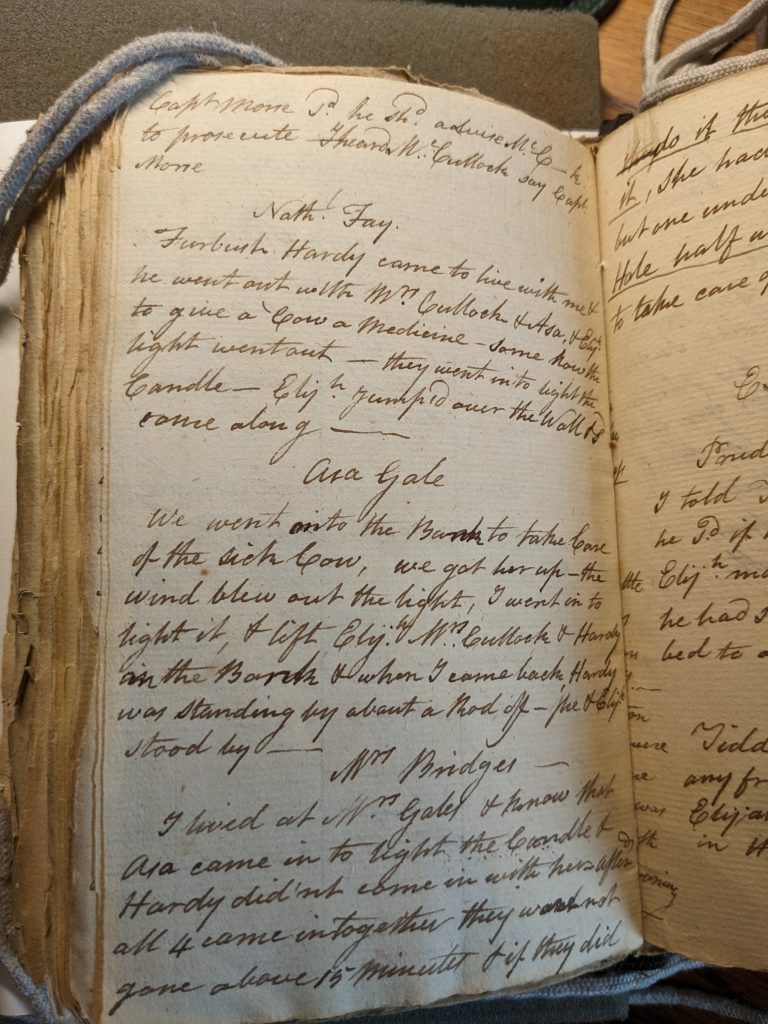

In Europe, England and the Netherlands declared war against each other in 1652, in what would later become known as the First Anglo-Dutch War. In North America, the copy of John Hull’s diary held by the Massachusetts Historical Society provides wonderful commentary on the growing tensions between New England and New Netherland at this time. The English colonists accused the Dutch of plotting against them with Indigenous groups. Hull, the Massachusetts Bay Colony mintmaster, described the visit of two commissioners from New England to New Netherland to discuss these accusations as “something that might further clear the righteousness of the war, or prevent it.” He was clear about the motivation of the visit, as many English colonists were clamoring for war with New Netherland.

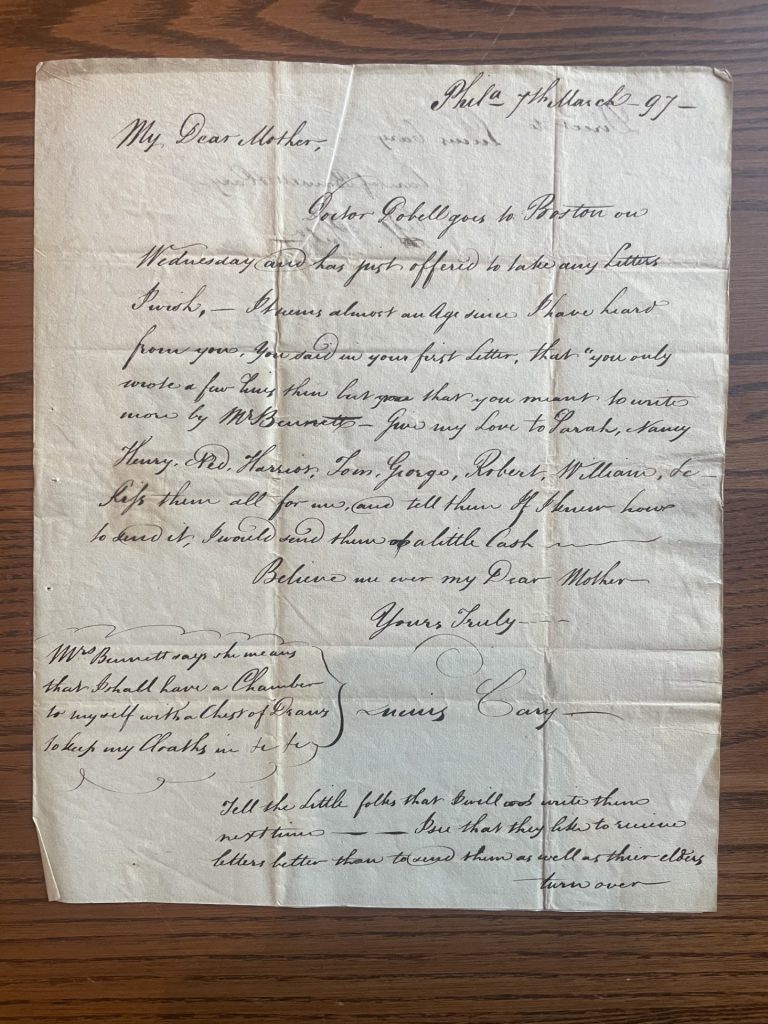

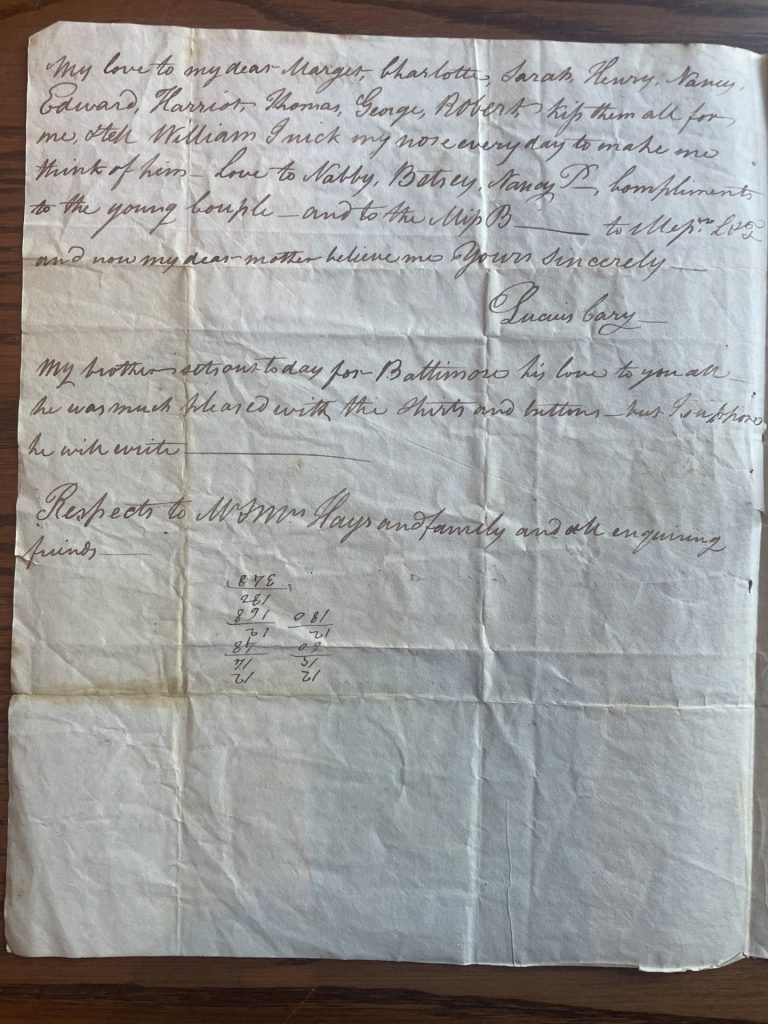

The Endicott Papers contain a letter of instruction to those commissioners that reflects previous frustrations. The letter insists that that “delays, slow and unsatisfying treaties… may not be admitted” from the Dutch. One of the signatories of the letter was John Endecott, the Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony:

Massachusetts Historical Society

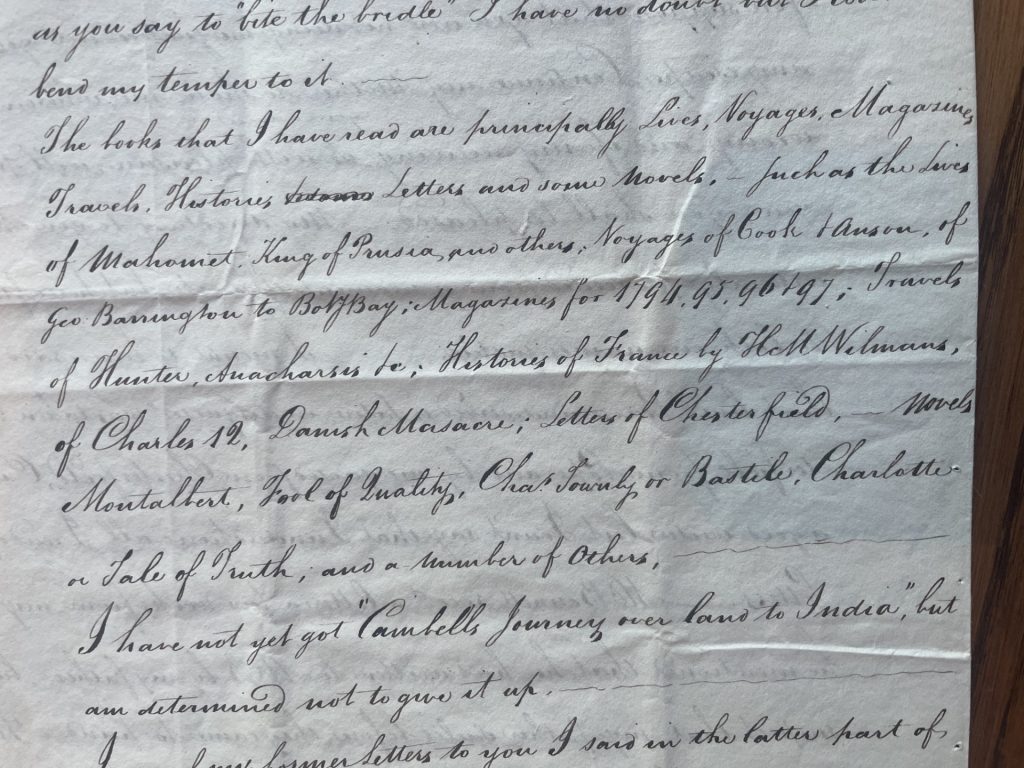

Endecott also wrote to John Winthrop, Jr., one of the magistrates of the Connecticut Colony, about New Netherland. Other letters to Winthrop are transcribed in the Winthrop Family Transcripts. John Haynes, the Governor of the Connecticut Colony, wrote to Winthrop with news of English naval victories over the Dutch forces in Europe. The painting below shows one of the major naval battles of the war:

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

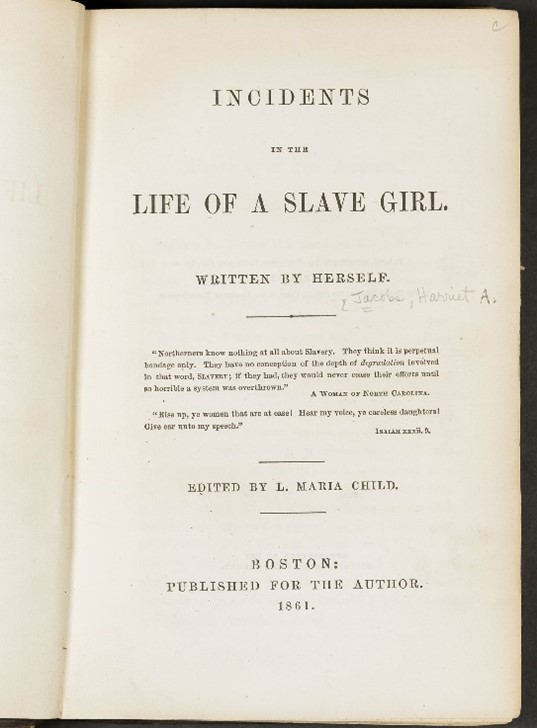

By 1654, the government in England responded to the desires of some colonies and decided to extend the war to North America. They sent ships of officers and soldiers to New England to plan an attack on New Netherland. Hull recorded in his diary that they were there “to root out the Dutch if they would not submit to the power and government of England.” The officers aimed to recruit 500 colonists to join their forces. However, in the middle of their planning and recruiting, a ship arrived with news from Europe: England and the Netherlands had signed a peace treaty, and the First Anglo-Dutch War was over. The attack on New Netherland was cancelled, and the English and Dutch colonies would remain neighbors for another decade.

Since the English colonists would take over New Netherland in 1664, why does their aborted attack in 1654 matter? It was a first step toward the eventual absorption of New Netherland into English North America. It provides an early example of colonial outposts becoming part of strategy in European wars. And the discussions among the colonists and the administrators in England about territory and sovereignty would contribute to their developing conceptions of empire. The Massachusetts Historical Society’s collection helps us to understand this story better and to see how it expands our view of early imperial history.