By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

After a long hiatus, I’m happy to return to my sporadic series about manuscript mysteries! As I’ve written in previous posts, sometimes the work of an archivist is like that of a detective: we follow clues, narrow searches, evaluate sources, and make educated inferences that hopefully lead us to an answer. Sometimes we’re waylaid and have to backtrack, and sometimes we come up empty, but I for one always enjoy a chance to don my deerstalker cap.

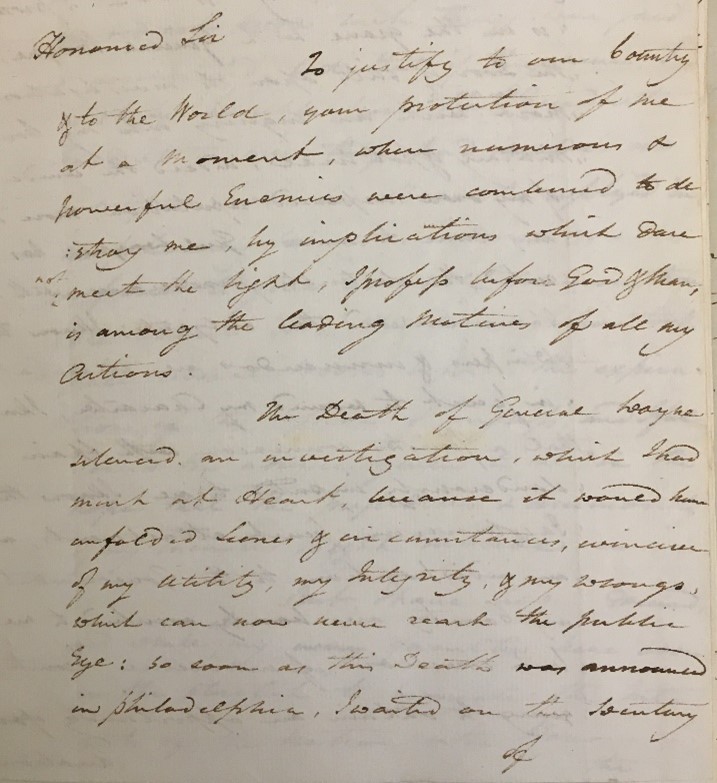

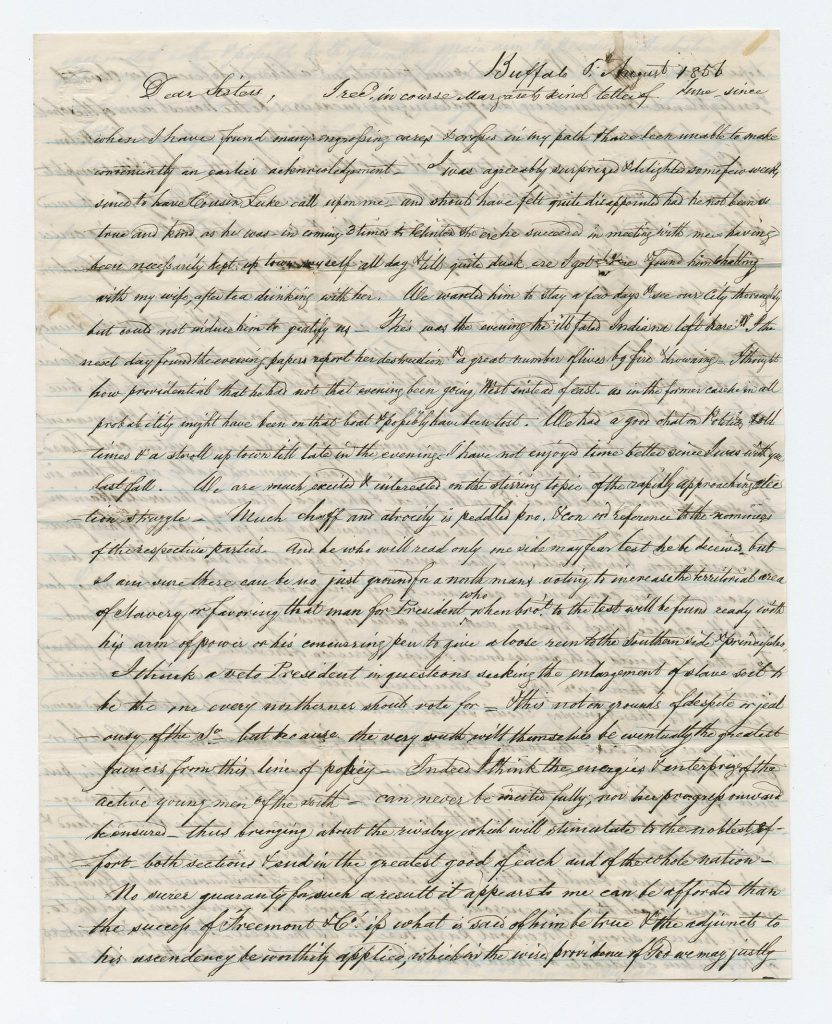

This time, I was looking for the man who wrote a letter, recently acquired by the MHS, dated 5 August 1856 and sent from Buffalo, N.Y. to Leominster, Mass. The text of the letter is interesting, if somewhat verbose. Among other things, it discusses the 1856 presidential election, a three-way race between James Buchanan, John C. Frémont, and Millard Fillmore.

Actually, I started on first base with this one, because I did know the man’s name: William Newman. He signed the letter “Yr devoted Brother Wm” and addressed it to Miss Anna B. Newman.

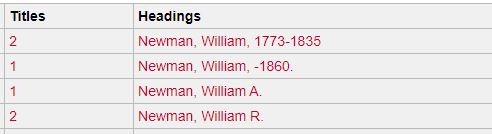

I could have left it at that, but I was determined to find out which William Newman he was, who Anna was, anything specific to help researchers that may be interested in this letter. After all, the MHS already had three different William Newmans in our online catalog ABIGAIL. The Library of Congress lists over 50 of them.

My first step was to gather clues. The last paragraph of a letter is a good place to look for specific names. A correspondent will often use this space to ask after family members or mutual friends. Besides William and Anna, I found a Luke (cousin), Margaret (possibly sister), and Caroline (no idea). William also mentioned a wife, as well as a son named William Henry who was apparently home for school vacation.

Unfortunately these names were too common for me to find a family genealogy at any of my go-to online sources: Internet Archive, Google Books, Ancestry.com, and Findagrave.com. Anna may have married and changed her surname. And the connection to Leominster was too tenuous; I couldn’t be sure if the Newman family hailed from there. Better to stick with what I knew.

I got my first break from a series of strategic online searches using Newman’s name, Buffalo, and 1856. And not for the first time, it was other archivists that came to my rescue. I found the Henry Newman family papers at the University of Michigan Library. Henry, originally from Boston, had a son named William who settled in Buffalo in the 1820s and established a business there. In our letter, William mentions buying some real estate.

I couldn’t be 100% sure yet, but the Michigan collection gave me a few crucial details. Their William married Lydia Scrafford (a much more distinctive name) and died in 1860. So I tried another search for confirmation. By adding his wife’s name to my keywords, I finally uncovered published records of a very messy court case related to the settlement of William’s will.

This was definitely my guy: died 4 April 1860, wife Lydia Scrafford, son William Henry Harrison Newman born in 1846. The records also included the names of siblings Henry, Jr., Margaret, Caroline, Anna, and Susan. (Interestingly, William was the only one to marry and have children.) The clincher was a passage referring to property on Clinton Street in Buffalo—property William mentioned in his letter.

William was apparently born in 1799 or 1800, assuming his tombstone is correct and he was sixty when he died. I identified his parents, Henry and Deborah (Cushing) Newman, and his wife Sarah Elizabeth née Cole, but found very little about his siblings. Henry, Jr. died in 1861, Susan in 1862, Margaret in 1866, and Anna in 1883.

These are just the dates of which I’m relatively confident. I don’t think I’ve ever seen so much conflicting information about a family I was researching! It goes to show how fallible the historical record can be and how important it is to find trustworthy sources.