By Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

In late October of 1915, as the days in New England grew shorter and the temperatures colder, twenty-seven-year-old Mildred Cox Howes of Brookline, Massachusetts, boarded a train with her husband, Osborne “Howsie” Howes, and headed west. Between 22 October and 14 November 1915 the couple traveled to California, where they attended the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. As was her habit, Mildred carried with her a line-a-day diary in which she recorded their movements, travel times, meals, friends met along the way, and sights seen.

Despite the fact that Mildred had recorded in early October spending time rolling bandages at a local hospital, presumably to be sent overseas, her own life was largely untouched by the reality of war in Europe. While England and the continent were digging in for the war to end all wars, the United States was in an expansionist, celebratory mood. Having recently flexed its imperialist muscles in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars (1898-1903), in 1914 the United States finally saw the completion of the Panama Canal (1903-1914) which dramatically increased the speed of an ocean voyage from the Atlantic to Pacific coasts of North America, saving ships nearly eight thousand miles of travel around Cape Horn. The Panama-California and Panama-Pacific International expositions were a message to the world regarding the United State’s new place on the world stage, as well as an opportunity for San Francisco, particularly, to celebrate its reconstruction following the devastating 1906 earthquake.

Mildred’s diary is spare, but does provide readers with a sense of the nature of upper-middle-class travel during the early twentieth century, before widespread adoption of the automobile. The Howes left Brookline on Tuesday, 22 October by the 12:34 train for Chicago. Mildred reported a “very pretty” ride through the Berkshires. Arriving in Chicago the following morning, they spent the day in Chicago visiting friends, dining out, and attending a garden show that Mildred described as “not much good.” Departing on an evening train, the Howes passed through Kansas and New Mexico, reaching the Grand Canyon a week after leaving home.

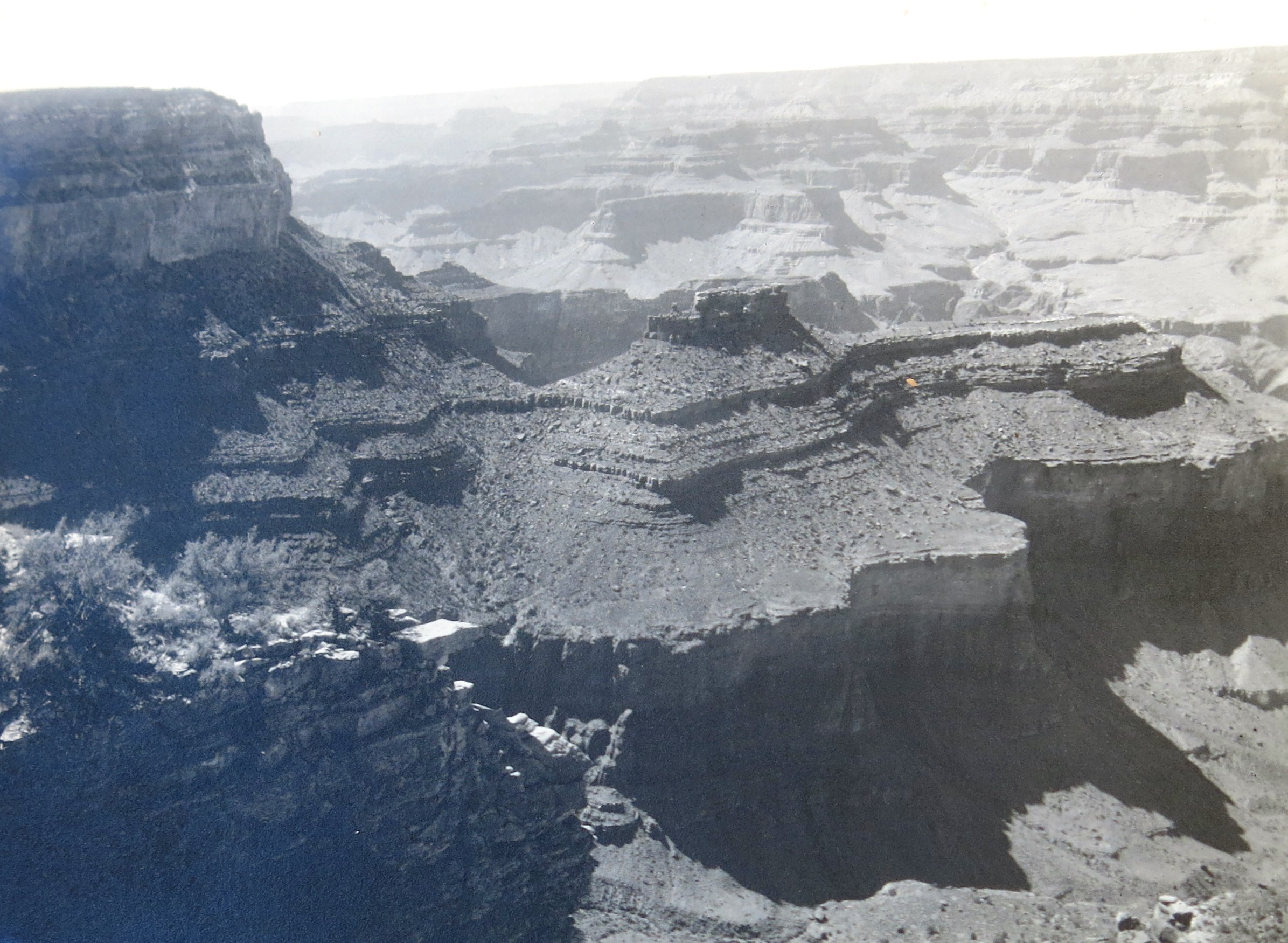

The Grand Canyon was not yet a national park (it would be dedicated in 1919), but nonetheless a popular tourist attraction. “About 10- we started & walked down to the plateau 5 miles & very steep,” Mildred wrote, “A guide & mule met us there …I rode up. Howsie walked. Fine. Wonderful views.”

The Howes reached San Diego the following day, after a morning spent traveling by train across the desert to Los Angeles, and then changing trains for the trip south to San Diego. They spent three days in San Diego, sunbathing at Coronado Beach, visiting the Panama-California Exposition, and driving down to Tijuana for a day (“Most amusing & just like a book”).

Departing from Coronado Beach by motorcar, the couple drove through Murietta Springs, Riverside, Pasadena, Los Angeles, arriving in Santa Barbara on Monday, November 1st. The automobile appears to have been as much for pleasure as transport, as Mildred repeatedly describes having “motored around” the cities they pass through, including a detour up to the top of Mt. Rubidoux, today a city park. Mildred also lists the names of the hotels at which the couple stay, often luxurious locations such as the Mission Inn (Riverside) and the Potter Hotel (Santa Barbara). When they arrive by train in San Francisco, they take up residence at the newly-constructed Palace Hotel, about three miles from the exposition — located between the Presidio and Fort Mason in what is today the Marina District.

“First [day] at the exposition – cleared off into a lovely day,” Mildred reported on November 4th. “Saw the manufactural palace & fibral arts… Dined at the hotel & went out again. Took a chair & looked at the illumination & listened to the bands.” Mildred and Howsie remained in San Francisco for a week, taking in the exposition and exploring the area. On exposition days, they arrived mid-morning and stayed until dinner, sometimes returning in the evening. On Saturday, Mildred reported going to the cinema to see “On Trial” (“very good & exciting”); on Sunday they took a Packard car and drove to Palo Alto for lunch with friends. On Tuesday they went to see Houdini perform at the Orpheum.

Twenty days after leaving Boston, Mildred and Howsie packed and, after a final morning at the fair, left at 4 o’clock on an eastbound train, traveling through Nevada to Ogden, Utah, and on across Wyoming and Nebraska at a brisk pace; they reached Chicago after three days’ steady travel, stopping the day to visit the art museum and stretch their legs. Boarding the train in Chicago they discovered friends Jessie and Frank Hallowell, and John Balcheder, also headed for Boston. By Sunday, November 14th, they were home once more.

Briefly factual in tone, Mildred’s diaries reveal only glimpses of her subjective experiences as a traveler, but nonetheless strongly evoke the rhythms of early-twentieth century travel for modern readers. If you are interested in this, and other diaries, kept by Mildred Cox Howes, you are welcome to visit or contact our library to access the collection.

**Photographs from Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Photograph Collection: Grand Canyon of the Colorado (#183.2043); Lotta’s fountain in front of the New Palace Hotel (#183.2022); Crowds at the Golden Gate Park (#183.2027).

1. It is always Christmas Eve in a ghost story.

1. It is always Christmas Eve in a ghost story.

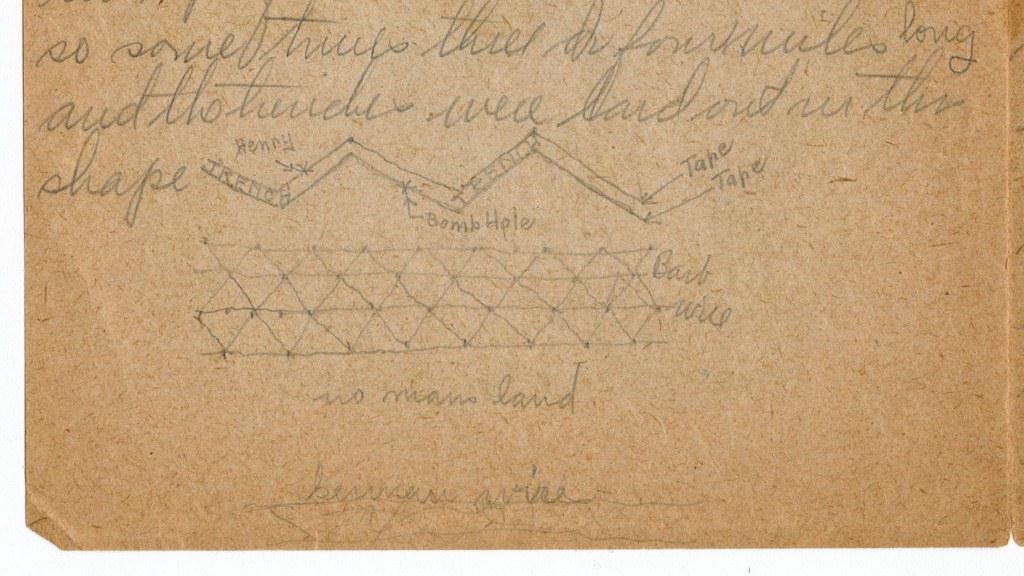

Some of them were written to anxious parents by very young soldiers, barely out of high school and full of bravado. Others come from older, battle-hardened men who write wistfully to their children while shells fall around them. Sometimes a soldier breezily anticipates the upcoming battle in which we know

Some of them were written to anxious parents by very young soldiers, barely out of high school and full of bravado. Others come from older, battle-hardened men who write wistfully to their children while shells fall around them. Sometimes a soldier breezily anticipates the upcoming battle in which we know